How WHO is an enabler of better health for all

The World Health Organization (WHO) plays an indispensable role in enabling countries to face the many health challenges of today. Like a lighthouse in the dark, WHO is a trusted source to provide direction and, if needed, customized assistance and critical resources. This article offers a snapshot of the many ways that WHO enables better health, from evaluating and delivering COVID-19 vaccines and diagnostic tests to backing a new malaria vaccine.

Transforming testing capacity across Africa

At the start of the pandemic, only one laboratory in Zimbabwe could test for COVID-19 and only a few laboratory scientists were trained. With WHO support, testing capacity was increased five times to 1000 tests a day by August 2020, with more engaged laboratories and trained staff. Yet, it still took 20–30 days to return test results to remote rural health centres. Many people went untested.

Diagnostic testing is critical to track and contain the virus, isolate infected people and detect variants. WHO has worked to make diagnostic tools accessible to countries – before SARS-CoV-2 had even been named, WHO was shipping test kits of a new PCR assay developed with Germany’s Charité University. With partners, WHO then made affordable antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests available in just 8 months – whereas it took 5 years for HIV. Although not a replacement for PCR tests, these tests are cheaper and easier to use, speeding up the pace of testing.

WHO’s Dr Muchaneta Mugabe at Beitbridge Hospital, training laboratory staff on a platform to test for COVID-19. © WHO Zimbabwe/ Tatenda Chimbwanda.

In Zimbabwe, rapid tests were a game changer, boosting testing capacity to an average of 11 000 tests a day at the COVID-19 peak in July 2021. With partners, WHO provided test kits and supported training in their use for over 6000 health-care workers, including district-level nurses. Testing is now available at more than 2000 sites, enabling people in remote areas to be tested. Laboratory infrastructure has also been scaled up, and WHO has monitored the quality of testing, with visits to 200 testing sites in all 10 provinces.

Similar support has been provided to other countries on the continent, with WHO supplying diagnostic tests and related training.

"Access to quality tests and laboratory services is like having a good radar system that gets you where you need to go. Without it, you’re flying blind."

WHO Director-General, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

WHO has run quality assessments of PCR testing from more than 1800 laboratories from 100 countries. ©WHO/ Blink Media-Juliana Tan

WHO has enabled a phenomenal expansion of testing capacity and laboratory infrastructure, providing support to 70 countries as of June 2021, exceeding WHO’s own target. In Africa, the transformation in testing capacity has been dramatic: in early February 2020, only two laboratories in Africa were capable of confirming a COVID-19 case; after 2 years and nearly 73 million COVID-19 tests later, 1029 laboratories on the African continent can do so. Genomic sequencing in southern Africa has also quadrupled, with a new regional centre for genomic surveillance. WHO is continuing to expand testing capacity and uptake, especially at subnational level.

In 2020 and 2021, WHO delivered 43 million COVID-19 diagnostic tests to 144 countries.

WHO: Trusted to evaluate new health products

Before any COVID-19 diagnostic test or vaccine is procured or delivered by WHO or its partners, it is first evaluated by WHO. The “emergency use listing” (EUL) procedure assesses unlicensed vaccines, therapeutics and in vitro diagnostics with the ultimate aim of expediting the availability of these products to people affected by a public health emergency.

An EUL balances the urgent need for and benefit of such products against potential risks, applying a stringent criteria for safety, efficacy and quality with available data. It is similar to WHO’s well-established prequalification process, but applies only in emergencies and is valid for 12 months and it can be extended, if necessary.

| WHO Emergency Use Listings approved in 2020 and 2021 | Number of products submitted | |

| Vaccines | 10 | 26 |

| In vitro diagnostics (IVDs) | 29 | 166 |

| Medicines | 3 finished products, 2 active pharmaceutical ingredients (dexamethasone)* | 9 |

*(A remdesivir product was also prequalified but was subsequently suspended)

An EUL from WHO serves as a green light or even a prerequisite for international procurement of new COVID-19 vaccines or diagnostic tests and is also recognized for market authorization by some countries. It speeds up the time for products to reach patients, as it allows national regulatory authorities to streamline their own evaluations, which can be challenging for some of the complex products on the market. Countries can base their regulatory decisions on WHO’s evaluations.

The EUL process can be intensive, with a lot of back-and-forth between manufacturers and WHO assessors. For vaccines, manufacturing sites must be inspected, which can be costly and time-consuming, particularly when inspectors need to go into quarantine, as was the case in China.

COVID-19 vaccines evaluation dossiers have been shared with 99 countries

Within only 15 days of WHO listing of one of the first vaccine for emergency use, 101 countries had issued national regulatory authorization.

A number of in-vitro diagnostics are still being assessed for possible design or quality improvement. Even if a product is not accepted for assessment or does not receive an EUL, WHO’s feedback on how to improve a product can be invaluable to the manufacturer. The EUL pathway proved critical to ensure safe and effective tests and vaccines reach patients more quickly in a pandemic.

Backing the world’s first malaria vaccine

The world’s first and only malaria vaccine is now recommended for wide use in children in Africa, thanks in part to a large pilot coordinated by WHO. In October 2021, WHO recommended the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine after the results of the pilot programme, in which more than one million children received the malaria vaccine during routine child vaccination services over 3 years in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi.

Described as a “breakthrough for child health and malaria control”, the vaccine is expected to save between 40 000 and 80 000 children a year, if introduced widely alongside insecticide-treated bed nets and other malaria control interventions. Despite gains made, malaria kills nearly half a million children under 5 years annually.

Engaging communities on the malaria vaccine. © WHO/ M.Niewenhof

The pilot established the vaccine’s public health value and upheld its strong safety profile. It showed a 30% reduction in hospitalizations and a decrease in all-cause mortality among children in real-world settings. The vaccine also significantly reduces the number of times a child gets sick with malaria. There has been strong community demand for the vaccine, as reflected by its high uptake. The pilot will continue into 2023 to answer questions on how to reach high uptake and the added benefit of the last dose of the four-dose regimen.

Coordinating a pilot of this size, a first for WHO, was a massive exercise, involving WHO at global, regional and country levels and across WHO departments, ministries of health and multiple public and private partners. WHO was uniquely placed for this role, which required the trust and working relationships with countries and partners. During the pilot, countries were also supported to strengthen nascent civil registration systems and pharmocovigilance – which later proved useful in the COVID-19 response.

WHO’s convening and coordinating role has been significant in the past 2 years. It includes the Solidarity Trial Vaccines, to find vaccines with greater efficacy and protection against COVID-19 variants of concern, and the Solidarity Therapeutics Trials with 13,000 patients, which showed that the four drug regimens tested had little or no effect.

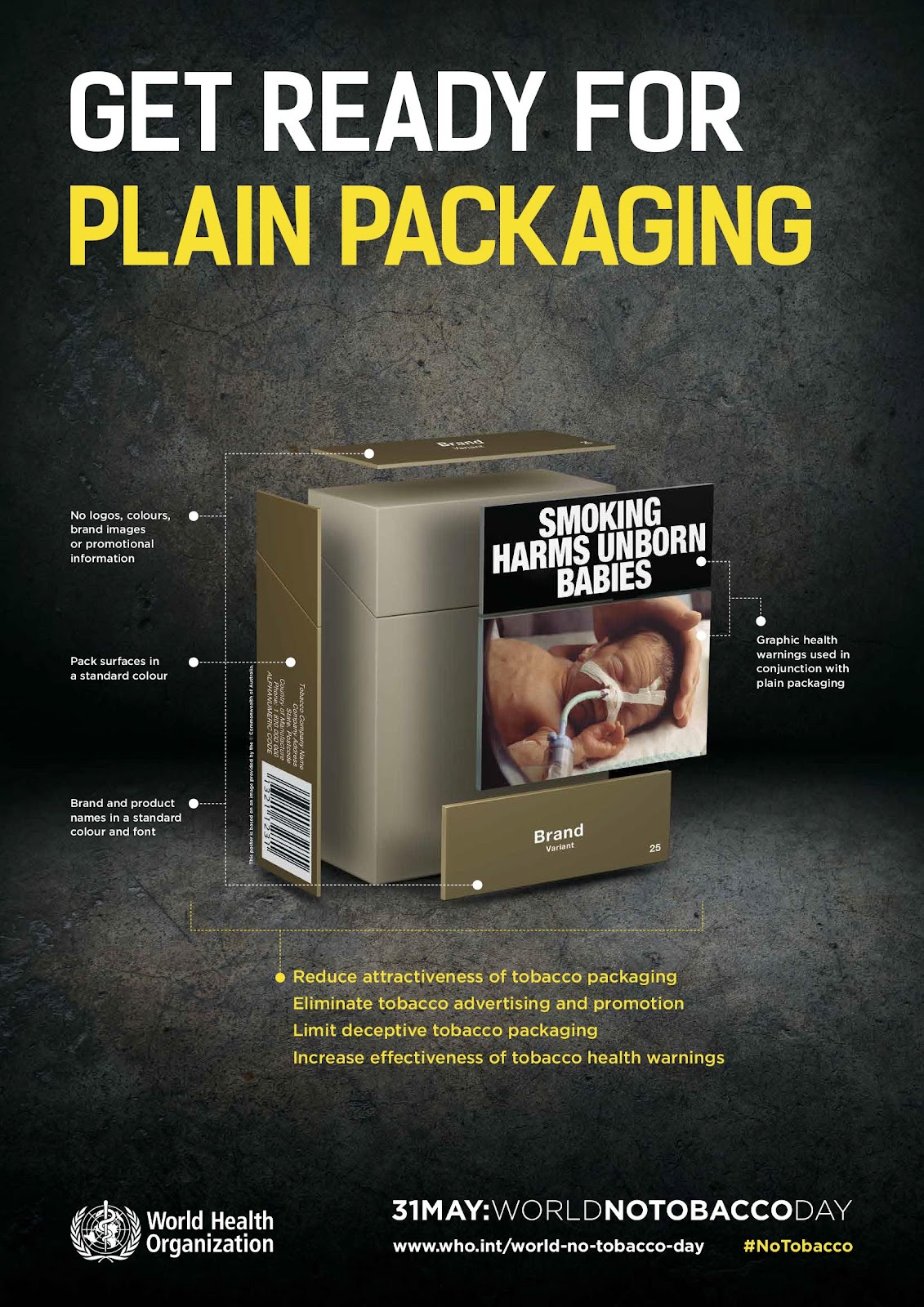

WHO has called for plain packaging of cigarette packets

WHO has called for plain packaging of cigarette packets

Unique power to create legal agreements

Across the global health community, WHO has the unique power to create legally-binding agreements with far-reaching impact. WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has spearheaded tobacco control measures that save millions of lives every year. A recent WHO report showed 69 million people had stopped using tobacco between 2000 and 2020, thereby reducing their risk of premature death due to measures taken by countries under the FCTC. Tobacco kills up to half of its users.

One of the most widely embraced treaties in UN history, the FCTC has been pivotal tobacco control tool, outlining measures to minimize tobacco demand and supply, such as advertising bans and large pictorial health warnings. Tobacco use is now on a downward trajectory in 150 countries. In the past 2 years, the number of countries on track to achieve the target of a 30% reduction in tobacco use between 2010 and 2025 has doubled to 60. Today, almost two thirds of the world’s population is fully protected by at least one demand reduction measure thanks to the FCTC, but far more needs to be done to ensure full implementation of measures.

From evidence gathering to capacitating countires

WHO enables better health in many other ways.

At the core of WHO’s work is evidence gathering, which WHO synthesizes into guidance and reports to facilitate decision-making. The wide spectrum of guidelines issued in 2021, which provide standards countries can rely on, address air quality, artificial evidence, HIV, hypertension, lead exposure and water quality.

WHO also provided evidence for action by monitoring the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on health systems in “Pulse Surveys”, which showed disruptions to health services in almost every country. One of the most severely disrupted services was rehabilitation, yet it has been found to be of increased, critical need during the pandemic for patients with post-intensive care syndrome and “long COVID”.

In 2021, WHO played multiple roles, including as a regulator, policy-maker and information resource, facilitating the world’s largest, fastest vaccination drive in history. Early in the pandemic, WHO helped expedite vaccine development with its “target product profile” for a potential vaccine. After vaccines are administered, WHO continues to review data on side effects (in pharmacovigilance).

WHO also enabled better access to quantified needs for lifesaving oxygen after countless deaths due to devastating shortages. WHO has revised the monograph on oxygen in the International Pharmacopoeia to ensure that only medicinal oxygen – and not industrial oxygen – that meets specifications for identity, purity and content, should be given to patients.

At the country level, WHO played an unprecedented, well-recognized leadership role in providing critical guidance to countries, partners and civil society during the COVID-19 response. With its 150 country offices, WHO provides hands-on help on the ground, including health services in fragile conflict areas.

At every level, everywhere, WHO works towards its goal for a healthier, safer and fairer world.

WHO has provided lifesaving COVID-19 tools to countries, such as oxygen, as seen here in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. © WHO / Fabeha Monir

WHO has provided lifesaving COVID-19 tools to countries, such as oxygen, as seen here in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. © WHO / Fabeha Monir