Health emergency preparedness after COVID-19: building for the future

In 2020, we saw that the world was not adequately prepared for a pandemic. COVID-19 is providing pointers for better preparedness.

The COVID-19 pandemic remains unprecedented in many respects, but it was not unforeseen. It is serving as a stark reminder that the costs of effective preparedness are dwarfed by the costs of failure to prepare.

While it is almost impossible to prevent unknown pathogens from emerging into high-threat diseases, adequate preparedness ensures that countries have the surveillance capacity to detect outbreaks rapidly, the rapid response systems to contain them and, if those fail, resilient public health systems to mitigate their impacts. In many cases, COVID-19 has shown that these capacities were not in place. The pandemic can provide valuable lessons as we work to break the cycle of panic and neglect that has blighted preparedness in the past.

The need for investment in preparedness

The pandemic was not unforeseen. Many recommendations and reports called to prepare for a pandemic. Just months before the first case of COVID-19 was reported, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) warned in a report: “There is a very real threat of a rapidly moving, highly lethal pandemic of a respiratory pathogen.”

Unfortunately, the world failed to heed the warning. Perhaps the investment in preparedness – estimated at US$ 5 per person a year – was considered too high. But the GPMB estimates in another report that the cost of the COVID-19 response so far is US$ 11 trillion, with a future loss of US$ 10 trillion in earnings. These figures show that preparedness yields a significant return on investment.

This is the most bitter lesson: despite repeated warnings of a threat, of the need to prepare and the costs of not preparing, the world collectively failed to prepare adequately for a pandemic.

WHO

Gaps remain in country capacities

Efforts to address pandemic preparedness date back two decades. The vulnerability of a globalized world to a fast-moving disease was evident after the 2003 SARS epidemic, which spread across continents in days.

In 2005, the International Health Regulations (IHR) were adopted, institutionalizing a legal framework for global health security. IHR (2005) was a paradigm shift. Countries were required to report potential public health emergencies of international concern to WHO and to ensure a set of core capacities to detect, assess, notify and report events. Progress in building those capacities has, however, been slow.

The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in 2014 in West Africa increased global recognition of the importance of preparedness; however, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown the consequences of the huge gaps in core capacities. In 2019, only half of all countries analysed had the capacity for operational readiness. WHO’s Assistant Director-General of Emergency Preparedness, Dr Jaouad Mahjour, said there has always been lack of political and financial commitment, with no sustainable funding from either domestic or global sources. National action plans for health security (NAPHS) to address critical gaps in preparedness gaps have been developed by 69 countries, but none is fully funded.

Weaknesses identified before the pandemic but which remained unaddressed included gaps in core capacities such as human resources and infection prevention and control.

There was no sustainable funding from both domestic and global sources.

Dr Jaouad Mahjour

WHO Assistant Director-General of Emergency Preparedness

The human dimension matters

The pandemic shows that any country, rich or poor, can struggle in its response, including those with high scores in IHR (2005) core capacities. Were some factors not accounted for? Yes, technical capacity alone is not enough: the human dimension counts.

As evidenced in the response to COVID-19, national leadership and coordination are critical for effective management of the response. Political commitment is a prerequisite for global and national preparedness. Communities also count. Sustained community engagement is essential as countries prepare for and respond to epidemics. Trust and social cohesion are necessary for a community-led response and determine the extent to which public health measures are accepted. Communities must be empowered to obtain accurate information and make informed decisions.

Another factor is that cities, which are home to many vulnerable populations, often have poor air quality and cramped housing and in many ways are designed to facilitate social interaction; thus, they often bear the brunt of cases. Heeding lessons from the pandemic, WHO is now developing an “urban preparedness network”.

A gender working group has also been set up to bridge the gaps in gender-inclusive, gender-responsive health emergency preparedness and response.

WHO, Blink Media/R. Shryock

Prioritizing public health in a post-COVID-19 world

The pandemic underscores the importance of essential public health functions and preventive measures. Some high-income countries have underinvested in these aspects in their mature health systems, instead prioritizing curative services. Basic public health measures – disease surveillance, contact tracing and quarantine – are key in the response.

Countries with experience of previous outbreaks were able to draw lessons or had already improved their public health infrastructure for an enhanced response. For example, after an outbreak of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Coronavirus in 2015, the Republic of Korea improved its disease surveillance, infection prevention and control procedures and laboratory systems.

A scoping review showed that health systems and health security are often treated as distinct fields, and this siloed approach presents challenges to health governance. WHO is developing a “health systems for health security” framework to identify the necessary capacities for health security, which will include surge resources during a health emergency while maintaining essential services.

Health systems and health security are often treated as distinct fields, and this siloed approach presents challenges to health governance.

Regional strategies on health security play an important role. These include the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases and Public Health Emergencies (APSED III) and the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response strategy (IDSR). Member countries benefit from the advice of technical advisory groups for implementation, information-sharing and peer support.

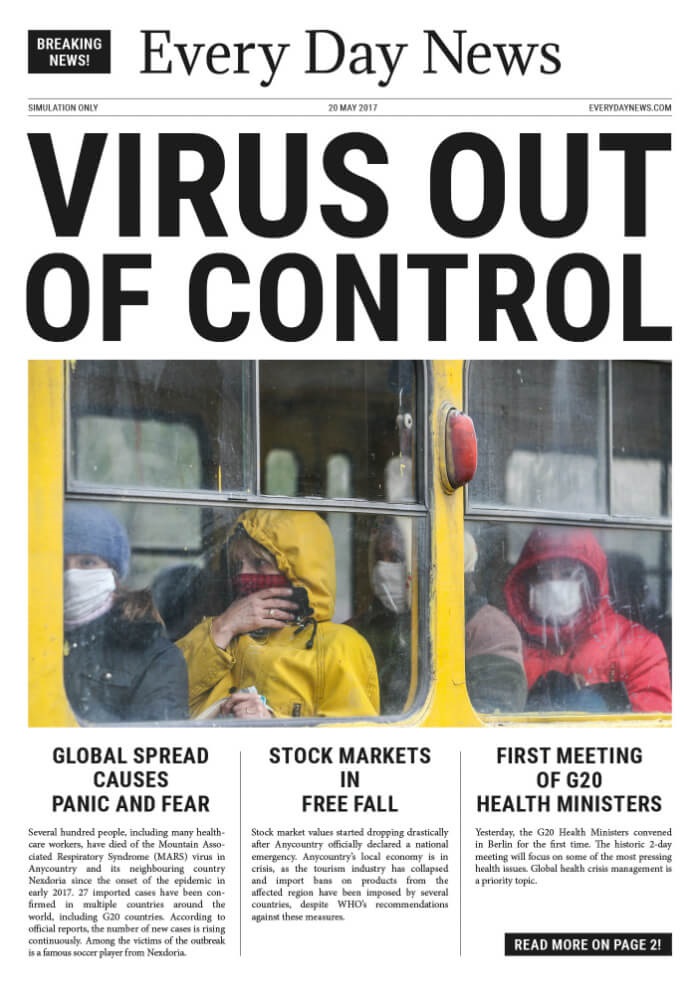

Outbreak in “Anycountry”

The newspaper banner headline ran: “Virus out of control!” The articles on the front page told a grim story of several hundred people, including many health workers, dying of a respiratory disease. The number of cases was rising, with imported cases confirmed in many countries. The stock market was in free fall, and health ministers were now meeting.

The epidemic in “Anycountry” was fictitious and was part of a simulation exercise at the meeting of G20 Health Ministers in Berlin, Germany, in May 2017 to raise the attention of ministers to the possibility of such a scenario. Three years later, it became a reality.

More than 150 of such simulation exercises have been conducted since 2016 to drive home the threat of a pandemic. In June 2019, the largest African cross-border field exercise was held at 23 sites with 250 participants.

Investing in influenza preparedness paid off

The impact of COVID-19 could have been far worse. The enormous amount of work done during the past decade to implement the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework laid down an important foundation for the COVID-19 response, providing vital infrastructure for disease surveillance, sample sharing and genomic analysis.

The extensive laboratory and surveillance network has been leveraged, with about 90% of national influenza centres testing for SARS-CoV-2, and over 50 000 sentinel specimens tested for the virus each week through the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). COVMart, which receives data on COVID-19, was built on influenza surveillance platforms.

Countries can also estimate disease burden better by using a WHO tool developed for PIP. Similarly, the regulatory roadmap developed by countries to approve products for pandemic influenza ensures regulatory readiness for COVID-19 vaccines, and readiness checklists and vaccine deployment plans developed for PIP have been adapted to COVID-19.

The learning platform OpenWHO.org, initially developed through PIP, ballooned in 2020, with over one million enrolments for the COVID-19 introductory course. The “Unity studies” for COVID-19 were adapted from a protocol developed by PIP.

Importantly, the capacity built by PIP is being used, thus contributing to country readiness for a pandemic.

The value of preparedness

Understanding of preparedness and related activities has increased, with more tools and guidance, such as WHO benchmarks to build capacity, electronic State Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting Tool (e-SPAR) for online self-assessment, One Health to bridge the animal, human and environmental sectors, and other tools under the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework. Can such means to measure preparedness be used as a marker for COVID-19 outcomes? No. Just having the capacities to respond to pandemics is not enough. Of critical importance is how countries use those capacities when a threat arises. Tools and metrics for pandemic preparedness must be strengthened continually to ensure the dynamic, time-sensitive core capacities required by IHR (2005). A more dynamic metric is being developed to gauge country capacities more comprehensively, including capacities not previously assessed as part of health security.

Interestingly, although a good SPAR or Joint External Evaluation (JEE) score has not necessarily predicted performance during COVID-19, an association was found between recent completion of a JEE and having an NAPHS with lower rates of COVID-19 cases. Although the association might be due to confounding factors, there is an operational rationale for an evaluation to enhance readiness. Dr Stella Chungong, Director of WHO’s Health Security Preparedness Department, said JEEs, NAPHS and simulation exercises are important tools for building multisectoral engagement and coordination. “You don’t hand out your business card during an outbreak to work together. You do it in peacetime,” she said.

You don't hand out your business card during an outbreak to work together. You do it in peacetime.

Dr Stella Chungong

WHO Director of Health Security Preparedness Department

The value of “after-action reviews” of a response to identify best practices, gaps and lessons learnt has been underscored during the pandemic. WHO therefore created “intra-action reviews” to correct and adjust responses to COVID-19. So far, 58 intra-action reviews have been conducted in 45 countries, and another 20 are planned.

WHO/S. Hasan

Solidarity, the way forward

The word “pandemic” is of Greek origin, meaning “all the people”. COVID-19 is affecting all people of all incomes, all ages and all colours. It is also affecting all sectors of government: the economy, travel, trade, education and the social sector. Pandemic preparedness therefore cannot be left to the health sector alone; it requires whole-of-societyand whole-of-government approaches with adequate resources and strong multisectoral coordination that meet an array of national interests.

We need leaders from top to bottom, federal to local, involved. We need global solidarity. The task is colossal, but so much is at stake.

Dr Mike Ryan

WHO Health Emergencies Assistant Director-General

Country preparedness is the cornerstone of global preparedness: a pandemic threat to one country is a threat to all countries. COVID-19 has revealed the result of chronic under-investment in pandemic preparedness. Financing pandemic preparedness must therefore be seen as an investment rather than a cost, with benefits to all countries.

The pandemic is resulting in renewed, more inclusive ways of working together through global collaboration, trust and accountability. This must continue beyond the pandemic.

Preparedness efforts must involve stakeholders across the spectrum. “We need leaders from top to bottom, federal to local, involved. We need global solidarity. The task is colossal, but so much is at stake,” said Dr Michael Ryan, WHO Health Emergencies Programme’s Executive Director. We cannot let the lessons provided by COVID-19 go unheeded. The time to break the “panic-then-forget” cycle is now.