New technologies can strengthen detection, but investment is essential to maintain capacities built during the COVID-19 response

Detect

Early detection, rapid risk assessment and clear communication are the foundations of an effective response to any health emergency. At global level, rapid detection and investigation of COVID-19 demonstrate the progress that has been made by WHO in public health intelligence, and funding for the COVID-19 response has enabled WHO regional offices to strengthen health emergency information management more broadly by introducing public health surveillance tools such as District Health Information Software 2 and the Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources system. This extended capacity provides a platform on which to build the global capacity necessary to detect the emergence of a health emergency and then monitor and guide the subsequent subnational, national, regional and global response.

Expansion of the Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources system broadened the scope of global public health surveillance and also streamlined and shortened the time required to validate and assess alerts. The system enabled WHO to sift through hundreds of thousands of potential signals every day in 2020, of which over 26 million were related to COVID-19. Funding for the COVID-19 response also enabled disease surveillance systems that record not only disease outbreaks in human populations but also information on potential risks at the human–animal interface (One Health) and signals related to climate change, industrial hazards and conflicts.

In all, WHO undertook 41 rapid risk assessments during 2020. But WHO’s role in public health intelligence extends far beyond initial detection and validation of signals to continuous monitoring of emergencies and their risks as they evolve over time. During COVID-19, continuous surveillance and monitoring at global level allowed detection and assessment of variants of concern, partly by adapting and leveraging influenza genomic surveillance networks, and continual reassessment of the appropriate public health and social measures for the evolving epidemiology.

Continuous public health intelligence and monitoring are equally important for operational management of more discrete subnational and national emergencies. WHO augments national capacities for emergency response by deploying standard tools and systems such as the Early Warning, Alert and Response System and Go.Data. In some countries, these tools were already being used to support national surveillance capacity for other health emergencies and could rapidly be adapted to the new pandemic.

One of the key challenges beyond COVID-19 and one of the greatest opportunities to shorten the time between emergence of a health hazard and its detection is strengthening national surveillance capacity as part of strengthening broader health emergency preparedness and readiness. This requires implementation of the recommendations of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) review committee to improve the tools available to national IHR focal points, and which emphasized the importance of ensuring that Member States effectively report and share information with WHO.

The aim is to move beyond detection of an event as the single driver of a change in operational readiness and response. The abundance and diversity of data now available, with the potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning, open the door to sophisticated predictive analytics and modelling, which could augment the rapid advances already under way in all-hazards surveillance. Realizing this potential will require transformation of WHO’s digital and data infrastructure as part of broader work to harness new and emerging technologies to improve the global system of health emergency preparedness, alert and response. Building global health emergency surveillance capacity based on 21st century technology is the only way to arm the world against 21st century threats. But these capacities can be built only if we sustain and institutionalize the capacity built in response to COVID-19.

Respond

COVID-19 rightly attracted most attention throughout 2020, but it was only one of 53 graded emergencies to which WHO responded during the 12-month period, which included concurrent public health emergencies of international concern such as the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and of polio in the Horn of Africa. Twelve new graded emergencies during 2020 required WHO to activate its emergency standard operating procedures, ranging from the global COVID-19 pandemic to the acute technological disaster of the Beirut Port explosion, natural disasters and complex humanitarian emergencies. The WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies was used for rapid responses and continuation of essential responses to 14 emergencies in all the WHO regions except that of the Americas. A total of US$ 43.7 million were allocated through the Fund during 2020, with 90% of initial releases made within 24 h of the initial request.

Within the Emergency Response Framework, WHO’s operational response to emergencies during 2020 was coordinated in the Incident Management System structure, which is based on recognized best practices in emergency management and is increasingly used by emergency management systems globally, including in the health sector. The COVID-19 response dominated activities and resources in 2020, with interoperable incident management support teams established in WHO headquarters, all regional offices and all country offices, drawing on partner expertise through the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network.

The initial rapid response to the emergence of COVID-19 was quickly followed by publication of the Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19, which united a global coalition of partners behind a common set of objectives. At global level, meeting the challenge of COVID-19 meant bringing the entire United Nations system together in a coordinated response that reflects the full spectrum of its capabilities. WHO was at the forefront of coordination, leading the Crisis Management Team, which brings the collective strengths of 23 United Nations entities under one response umbrella. At national level, WHO played a facilitating and coordinating role through the COVID-19 Partners Platform, a mechanism to plan, resource and track implementation of national action plans by integrating United Nations country teams, implementing partners and donors.

In all the pillars of the response to COVID-19, WHO scaled up and leveraged existing and new operational and partnership platforms to ensure that the Organization’s evidence-based technical knowledge was translated into tangible impacts at national and subnational levels. The WHO-led COVID-19 supply chain system is a perfect illustration of such end-to-end integration of technical and operational capacities for impact. From technical specifications and quality assurance by WHO’s technical experts through procurement and distribution through the logistics capabilities and joint purchasing power of WHO and partners, WHO procured and shipped more than US$ 1 billion of essential response supplies, including vital medical oxygen, personal protective equipment and more than 250 million COVID-19 tests to 184 countries during 2020.

The Tech Science for Health network brought together multidisciplinary technical expertise and operational capacity to revolutionize the approach to designing and constructing emergency treatment facilities, enabling the establishment of 3659 treatment beds for patients with severe acute respiratory illness in 17 countries. Access to an emergency health workforce was coordinated through the Emergency Medical Teams initiative, which facilitated over 70 international medical support missions and provided technical standards and support for the mobilization of more than 800 national medical teams during 2020. In addition, WHO directly deployed hundreds of teams and missions to strengthen critical national and subnational responses to COVID-19.

A large proportion of WHO’s direct support for the COVID-19 response and most operational support for all-hazard emergencies during 2020 was focused on contexts affected by fragility, conflict and violence. Meeting the health needs of populations in such contexts will be a key determinant of whether the world will achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. The World Bank has estimated that, by 2030, up to two thirds of the world's extremely poor could live in such settings. The majority of preventable maternal and neonatal deaths and deaths from preventable infectious diseases occur in contexts affected by fragility, conflict and violence. Although the trend over the past several decades has been positive, the pace of improvement is not sufficient to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

Conflict, which has been increasing since 2010, accounts for 80% of humanitarian needs, and the complex interplay between conflict, climate change, rising inequality and demographic change is increasing fragility and vulnerability. The COVID-19 pandemic has hit populations in such settings especially hard. In addition, it has been especially difficult to conduct emergency response operations with health-sector partners because of the unprecedented scale and nature of the disruption caused by the pandemic, which has exacerbated pre-existing impediments to implementation such as limited humanitarian access, insufficient funding to ensure the delivery of sustainable, continuous life-saving health services to crisis-affected vulnerable populations, attacks on health care workers and facilities and escalating field costs.

As the lead agency for health of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, WHO can operate in and access some of the most difficult-to-reach populations to ensure essential health services. During 2020, WHO led integration and delivery of the public health response to COVID-19 by implementing the Global Humanitarian Response Plan for COVID-19, providing coordination and operational support in 30 countries, with 900 national and international partners, to meet the essential health needs of 90.8 million people.

The response to COVID-19 has shown that the approach to delivering essential health services must evolve, with strengthening of resilience and health security. Strengthening of health systems as a means to achieve universal health coverage has been at the centre of WHO’s work for many years; however, it has not yet been effectively integrated with strengthening of preparedness, response and recovery capacities for health security. Chronic underinvestment in essential public health functions, in particular those relevant to IHR emergency risk management, has resulted in a pattern in which reactions to events that are recurrent and predictable come at high socio-economic cost, with inadequate investment in risk reduction and preparedness capacities that would reduce the negative impact of future events. Breaking this pattern of panic and neglect is especially urgent in settings of fragility, conflict and violence, where most epidemics occur and where there are additional hazards that periodically acutely exacerbate protracted emergencies.

A better-integrated approach in such contexts, grounded in primary health care that builds trust with communities, would both ensure safe access to resilient health services and ensure that basic capacities for all-hazard emergency risk management are in place. Achieving this will require a new funding model for supporting fragile countries experiencing conflict and violence and sustainable core resources for WHO to maintain a country presence in order to deliver a consistent package of technical and operational support.

To find progress on health outcome indicators, visit the World health statistics

Strengthening health systems to get to ‒ and stay at ‒ ZERO malaria cases

Malaria eliminated in 10 countries in 5 years

The elimination target was set by the WHO global malaria strategy. A country that was malaria-endemic in 2015 had to achieve at least one year of zero indigenous cases and then maintain that status through the end of 2020. Countries that reach at least 3 years of zero indigenous cases are eligible to apply for an official WHO certification of malaria elimination.

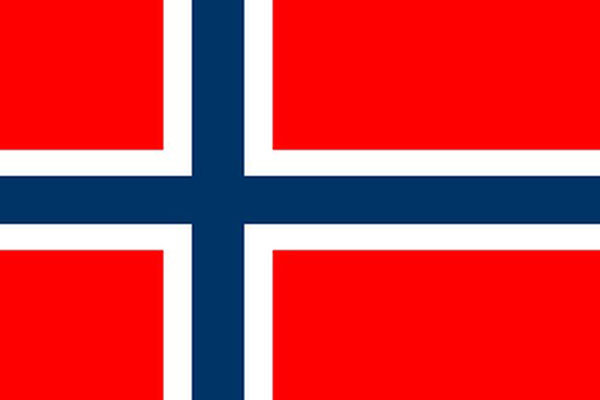

Strong public health system infrastructure with skilled, motivated personnel, signed Tashkent declaration with 8 neighbouring countries to scale up response and interrupt transmission completely

Strong public health system infrastructure with skilled, motivated personnel, signed Tashkent declaration with 8 neighbouring countries to scale up response and interrupt transmission completely

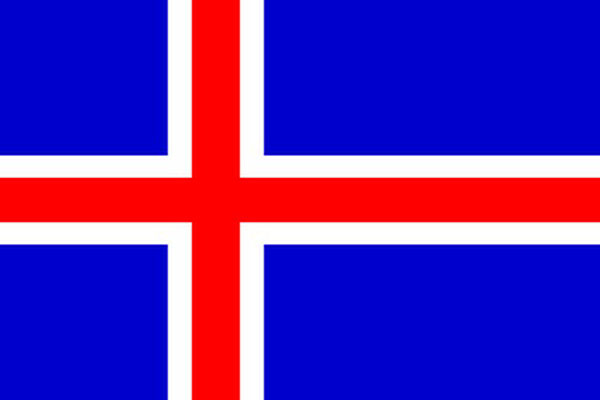

Reoriented surveillance according to risk stratification to focus on areas where people are more likely to be affected and maintains surveillance in ports and airports

Reoriented surveillance according to risk stratification to focus on areas where people are more likely to be affected and maintains surveillance in ports and airports

All patients are treated by the public sector with at least 3 days of hospitalization, which helps to improve rates of adherence to medication

All patients are treated by the public sector with at least 3 days of hospitalization, which helps to improve rates of adherence to medication

Inter-ministerial effort in health, education, finance, research and science, development, public security, the army, police, commerce, industry, information technology, the media and tourism

Inter-ministerial effort in health, education, finance, research and science, development, public security, the army, police, commerce, industry, information technology, the media and tourism

Maintains a network of > 3000 community health workers to identify imported cases early before they transmit infections onwards

Maintains a network of > 3000 community health workers to identify imported cases early before they transmit infections onwards

Diagnosis, treatment and prevention provided free of charge, including for migrant workers from neighbouring countries, and volunteers trained in use of rapid diagnostic tests and compliance with treatment regimens

Diagnosis, treatment and prevention provided free of charge, including for migrant workers from neighbouring countries, and volunteers trained in use of rapid diagnostic tests and compliance with treatment regimens

Extensive surveillance system in villages and stratification based on risk of mosquito bites and likelihood of importation particularly on plantations where labourers who often travel receive treatment free-of-charge

Extensive surveillance system in villages and stratification based on risk of mosquito bites and likelihood of importation particularly on plantations where labourers who often travel receive treatment free-of-charge

Effective surveillance combined with mobile clinics enabled prompt, effective treatment in areas of high transmission in the middle of a civil war

Effective surveillance combined with mobile clinics enabled prompt, effective treatment in areas of high transmission in the middle of a civil war

Districts still have reserve stocks of anti-malarial drugs, insecticides and bednets, and health education continues for population in higher-risk areas

Districts still have reserve stocks of anti-malarial drugs, insecticides and bednets, and health education continues for population in higher-risk areas

Operational guidance on

maintaining essential health services during COVID-19

rapidly developed to support countries adapt their strategies

A new manual provides guidance on

preparing for the official WHO certification

of malaria elimination

Tailoring malaria interventions to the COVID-19 pandemic provides guidance on

adapting interventions during the evolving emergency

and associated restrictions

Malaria Elimination Oversight Committee established to

share issues that could threaten elimination

and maintain a 360° view of the work of countries and regions towards malaria elimination

Convening Member States to share

innovations and best practices

Comprehensive framework of

tools, activities and dynamic strategies

that can be adapted to the local context

Malaria Elimination Certification Panel established to review evidence that a country has interrupted

the chain of indigenous transmission for at least 3 years

and has a programme to prevent re-establishment

Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030 set the target to eliminate malaria in 5 countries by 2020.

Guidelines on

treatment

of malaria with primaquine and artemisinin-based combination therapy

10 years since world health report "Health systems financing: the path to universal health coverage"

-1.png?sfvrsn=872dd4cb_3)

-1.png?sfvrsn=a7b784e6_5)

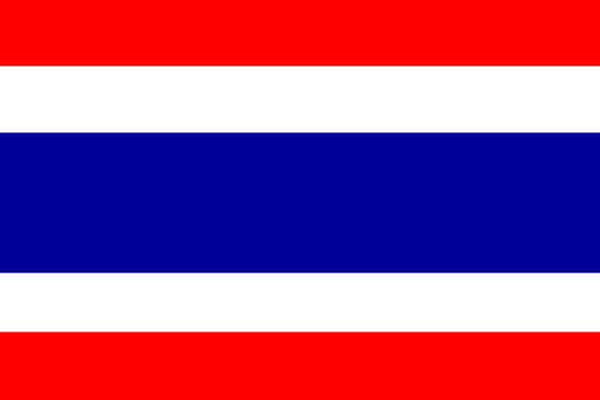

Launched a Universal Coverage UHC scheme in 2012, which resulted in 98% of the population with coverage, at a cost to the Government of US$ 80 per beneficiary

Because we are poor, we cannot afford not to have universal health coverage.

Thai Minister of Public Health on Universal Health Coverage Day, 2016

Launched a Universal Coverage UHC scheme in 2012, which resulted in 98% of the population with coverage, at a cost to the Government of US$ 80 per beneficiary

Because we are poor, we cannot afford not to have universal health coverage.

Thai Minister of Public Health on Universal Health Coverage Day, 2016

Large, predominantly government participation in health care and services in public facilities provided free at point of delivery and little private expenditure; however, financial hardship due to large household expenditure on health has slightly increased.

| Coverage of essential services | < 10% household expenditure on health |

|---|---|

| Improved from 24/100 (2000) to 52/100 (2017) | Worsened from 2.6% (2001) to 2.9% (2014) |

Coverage of essential services should be improved; e.g. only 57% of births are attended by skilled personnel and only 73.5% of children are fully vaccinated by 12 months of age.

*

Large, predominantly government participation in health care and services in public facilities provided free at point of delivery and little private expenditure; however, financial hardship due to large household expenditure on health has slightly increased.

| Coverage of essential services | < 10% household expenditure on health |

|---|---|

| Improved from 24/100 (2000) to 52/100 (2017) | Worsened from 2.6% (2001) to 2.9% (2014) |

Coverage of essential services should be improved; e.g. only 57% of births are attended by skilled personnel and only 73.5% of children are fully vaccinated by 12 months of age.

*

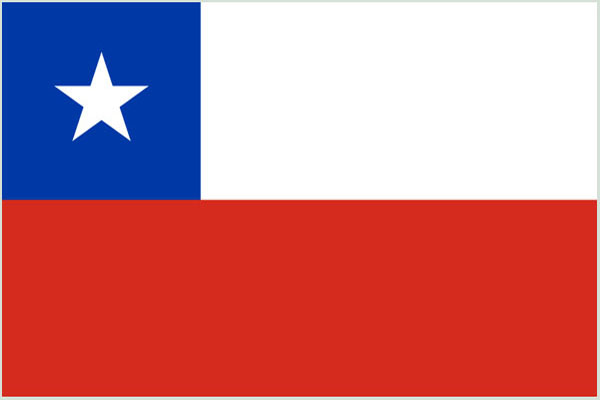

Tripled public spending on health in a decade, increasing public expenditure on primary health care to 37%, as compared with a regional average of < 15%

| Coverage of essential services | > 10% household expenditure on health |

|---|---|

| Improved from 41/100 (2000) to 68/100 (2017) | Improved from 11.06% (2000) to 6.02% (2016) |

1 in 3 Latin American countries close to reaching the goal of allocating 6% of GDP towards public health.

Tripled public spending on health in a decade, increasing public expenditure on primary health care to 37%, as compared with a regional average of < 15%

| Coverage of essential services | > 10% household expenditure on health |

|---|---|

| Improved from 41/100 (2000) to 68/100 (2017) | Improved from 11.06% (2000) to 6.02% (2016) |

1 in 3 Latin American countries close to reaching the goal of allocating 6% of GDP towards public health.

WHO launches Health Financing Progress Matrix to monitor

policies that directly contribute

to improved financial protection and service coverage

3rd global monitoring report shows divergent progress towards UHC since 2000:

catastrophic health spending

and recommends

United Nations Member States adopt high-level political declaration to ensure that everyone has access to essential health services without experiencing financial hardship

Support provided:

- options for a health financing policy;

- knowledge on crucial aspects and implications of a new policy, including governance financing, management of health services and integrated health service networks; and

- facilitation of discussions with stakeholder to ensure buy-in to a new policy

2nd global monitoring report shows:

1st global monitoring report tracks countries’ progress towards universal health coverage:

.png?sfvrsn=e49c8af_3)

Resolution WHA64.9 requests the Director-General to approve a plan of action to support Member States in realizing universal coverage as envisaged by the World Health Report 2010

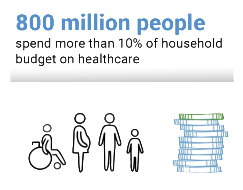

Member States urged to ensure health financing is available to implement policies to avoid catastrophic health-care expenditure and impoverishment as a result of seeking care.

The World Health Report 2010 on health systems financing provides a

road map

to achieving universal health coverage after the global financial crisis in 2009

Revolutionizing access to medicines across the globe

The WHO model list of essential medicines has played a central role in mitigating the most damaging effects of HIV, and other diseases as well.

Today, the list serves as a tool to guide member countries' selection of medicines and policies against two major global crises: antibiotic resistance and the surge of cancers. When we face health and welfare calamities, the WHO model list can lead the way to strengthen human rights and health-based medicine policies.

90% of essential medicines | |||

on the WHO model list of essential medicines can be subjected to competition only 5-10% are patented agents |

90% of essential medicines | |||

on the WHO model list of essential medicines can be subjected to competition only 5-10% are patented agents |

20 m people | US$ 1.96 b saved | |

| worldwide have access to antiretroviral treatment | in international procurement of HIV and hepatitis C medicines and supplied 50 m patient-years of treatment over last 8 years |

20 m people | US$ 1.96 b saved | |

| worldwide have access to antiretroviral treatment | in international procurement of HIV and hepatitis C medicines and supplied 50 m patient-years of treatment over last 8 years |

Most countries selecting WHO-recommended medicines for primary care and infectious diseases

More should select WHO-recommended specialty medicines, e.g. for cancer

Most countries selecting WHO-recommended medicines for primary care and infectious diseases

More should select WHO-recommended specialty medicines, e.g. for cancer

WHO target: ≥ 60%

of consumption of antibiotics worldwide from “Access” group of the AWaRe classification

WHO target: ≥ 60%

of consumption of antibiotics worldwide from “Access” group of the AWaRe classification

21st WHO model list of essential medicines comprises

460 medicines

- 1 in 4 medicines listed in 1977 are still essential

- 90–95% of all essential medicines are available as generics or biosimilars

1st WHO model list of essential in-vitro diagnostic comprises

113 diagnostics

20th WHO model list of essential medicines and 16th WHO model list of essential medicines for children include the

AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) classification of antibiotics,

after a comprehensive review, to support surveillance of antibiotic use and stewardship to promote adequate prescription practices

Global Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance – to

strengthen health systems to ensure more appropriate use

of and access to antimicrobial agents

19th WHO model list of essential medicines includes

first monoclonal antibodies

for treating cancer (e.g. trastuzumab, rituximab), after a comprehensive review of cancer medicines

100 developing countries receiving continuous supply of essential medicines to treat HIV and hepatitis B, as a result of a first agreement between the Medicines Patent Pool and a pharmaceutical company

Voluntary licensing and patent pooling

for low- and middle-income countries facilitated by newly established Medicines Patent Pool

Almost 100% of donor-funded antiretroviral market comprises generics, saving hundreds of millions of US dollars

> 60 countries

procure large quantities of antiretroviral drugs at a lower cost by listing them as essential medicines and by enforcing the trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPS) flexibility in the Doha Declaration

1st WHO model list of essential medicines for children comprises 119 medicines in appropriate dosages and formulations

WHO and UNAIDS launch the

“3 by 5” campaign

3 million people on antiretroviral treatment by 2005– as lack of HIV/AIDS treatment is declared a global health emergency

12th WHO model list of essential medicines includes

several antiretroviral drugs under patent

Right to health

recognized to include access to medicines in World Health Assembly resolution and the World Trade Organization Doha Declaration

Brazil, South Africa, Thailand and Zimbabwe led discussions on granting access to essential medicines for pandemics, such as HIV/AIDS, and recognizing that the right to health includes access to medicines

This legitimizes generic substitution, which provides momentum for countries to challenge excessive pricing by multinational pharmaceutical companies

11th WHO model list of essential medicines comprises

306 Medicines

156 official national lists

of essential medicines

Triple-drug therapy found to durably suppress viral replication of HIV to minimal levels, but

antiretroviral medicines available only sporadically |

in most countries

WHO action programme established to increase availability of essential medicines at primary health care level by strengthening countries:

- national capabilities in their selection, procurement, distribution and proper use and

- local production and quality control.

Sets the basis for guidance on centralized procurement and conditions to encourage local production

Kenya, South Africa, Sudan and Viet Nam are early adopters of the WHO quality system – training prescribers and drafting an initial list of 40 medicines to encourage pooled purchasing

World Health Assembly resolution endorses a model list of essential drugs

Alma-Ata conference identifies essential medicines as

one of eight key components of primary health care

1st WHO model list of essential medicines comprises

208 medicines

for primary care and hospitals, rare and frequent diseases and conditions, high- and low-cost medicines

Protecting people from the health impacts of climate-related risks

Improve resilience of health systems to climate variability and change

As an example, climate-resilient water safety improved for:

- 2.5 million people in Ethiopia using 50 water supply systems, 2020

-280 000 people in Nepal, 2020

-605 000 people in Bangladesh, 2020

-240 000 in urban areas of the United Republic of Tanzania, and 6200 people in rural areas, 2017

Simple, low-cost interventions, such as building retaining walls or ditches, prevent contamination of drinking-water during flooding; and planting indigenous trees protects the water table in Ethiopia, 2018.

.jpg?sfvrsn=6706eada_9)

As an example, climate-resilient water safety improved for:

- 2.5 million people in Ethiopia using 50 water supply systems, 2020

-280 000 people in Nepal, 2020

-605 000 people in Bangladesh, 2020

-240 000 in urban areas of the United Republic of Tanzania, and 6200 people in rural areas, 2017

Simple, low-cost interventions, such as building retaining walls or ditches, prevent contamination of drinking-water during flooding; and planting indigenous trees protects the water table in Ethiopia, 2018.

For example, the assessment in:

- Lao People’s Democratic Republic studied the links between climate change and water-related and vector-borne diseases; water, sanitation and hygiene; mental health; malnutrition; injury and disability; and sudden increases in health service use.

- Madagascar highlighted the health impacts of flooding, cyclones, drought, heatwaves and cold spells, 2015

Health national adaptation plans are informed by the assessments and include:

- Timor-Leste plan for health sector adaptation to climate change finalized in wide consultation with partners, 2019

- health national adaptation developed and endorsed in Nepal, 2018

- climate change action plan for public health officially endorsed by the Ministry of Health in Cambodia, 2020

For example, the assessment in:

- Lao People’s Democratic Republic studied the links between climate change and water-related and vector-borne diseases; water, sanitation and hygiene; mental health; malnutrition; injury and disability; and sudden increases in health service use.

- Madagascar highlighted the health impacts of flooding, cyclones, drought, heatwaves and cold spells, 2015

Health national adaptation plans are informed by the assessments and include:

- Timor-Leste plan for health sector adaptation to climate change finalized in wide consultation with partners, 2019

- health national adaptation developed and endorsed in Nepal, 2018

- climate change action plan for public health officially endorsed by the Ministry of Health in Cambodia, 2020

Climate and weather information integrated into health surveillance and early warning systems to predict outbreaks, such as:

- cholera in Bangladesh and Malawi, 2020

- malaria in Mozambique, 2020

- dengue fever in Myanmar and Timor-Leste, 2020

Climate and weather information integrated into health surveillance and early warning systems to predict outbreaks, such as:

- cholera in Bangladesh and Malawi, 2020

- malaria in Mozambique, 2020

- dengue fever in Myanmar and Timor-Leste, 2020

Action towards climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health care facilities, for example:

- in 62 health care facilities in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2020

- assessments conducted in 25 health centres in Cambodia with focus on climate-resilient WASH, 2020

/feature-stories/cambodia-4.jpg?sfvrsn=19d9a2f1_7)

Action towards climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health care facilities, for example:

- in 62 health care facilities in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2020

- assessments conducted in 25 health centres in Cambodia with focus on climate-resilient WASH, 2020

Action to build climate-resilient health systems in small island developing states, includes:

18 country profiles on health and climate change completed to inform evidence-based decision-making when strengthen the resilience of health systems, 2021

US$ 33-65 m funding mobilized to small island developing states to strengthen the resilience of health systems, health-care facilities, schools and communities to climate change

Action to build climate-resilient health systems in small island developing states, includes:

18 country profiles on health and climate change completed to inform evidence-based decision-making when strengthen the resilience of health systems, 2021

US$ 33-65 m funding mobilized to small island developing states to strengthen the resilience of health systems, health-care facilities, schools and communities to climate change

Quality criteria for evaluating climate-informed early warning and response systems for infectious diseases developed

WHO approved as a Green Climate Fund Readiness Delivery Partner

– resulting in 7 Caribbean countries and Argentina securing US$ 1.3 m funding

WHO guidance provides a set of interventions to improve climate resilience while decreasing the environmental impact and carbon footprint of health care facilities

12 countries trained in developing and implementing climate-informed health early warning systems

Support provided

to integrate information on climate and weather

into health surveillance and early warning systems to predict outbreaks of climate-sensitive diseases

WHO technical series for

assessing current and future vulnerability to specific health risks

beginning with undernutrition

Global plan of action on climate change and health in small island developing states

Guide and case studies for

developing climate services for health

with the World Meteorological Organization

WHO guidance for water safety

planning to improve the resilience of water supplies

to climate variability and change published

Special initiative on climate change and health

in small island developing states launched at the

23rd Conference of the Parties (COP23) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

WHO guidance published for

developing a health national adaptation plan

which is integrated into national climate change adaptation planning

Eliminate industrially produced trans fats from the global food supply by 2023

58 countries have introduced laws that will protect 3.2 billion people by the end of 2021

However, most are high- and upper- to middle-income countries. More than 100 countries still need stronger action, including those where a high proportion of coronary heart disease is due to intake of trans fats

Best-practice policy takes effect (2009)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2009)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2018)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2018)

First country to legislate a limit on trans fat content in all food products, 2g/100g of total fat; best-practice policy to take effect 1 year later (2003)

First country to legislate a limit on trans fat content in all food products, 2g/100g of total fat; best-practice policy to take effect 1 year later (2003)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2014)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2014)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2011)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2011)

.png?sfvrsn=acb09e00_5)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2014)

Best-practice policy takes effect (2014)

Country certification of trans fat elimination first programme to

recognize elimination of a risk factor

for noncommunicable diseases

Second global progress report launched by WHO Director-General to countdown in 2023

REPLACE action package provides a

strategic approach to eliminating

industrially produced trans fats from national food supplies

Supported Member States in strengthening capacity to develop, update and implement legislation

First global progress report launched by WHO Director-General to countdown in 2023

Dialogue with the food and non-alcoholic beverage industries at Chatham House

Call to action to Member States to eliminate trans fats from the food supply by 2023

“Eliminating industrially-produced trans fat is one of the simplest and most effective ways to save lives and create a healthier food supply”

– Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Updated draft of WHO guideline on trans fats issued for public consultation, recommending that

corresponding to 2.2 g/day of a 2000-calorie diet

REPLACE action framework to serve as a roadmap for country actions

Legislating to ban use of trans fats in the food chain included as part of cost-effective interventions to

prevent and control noncommunicable diseases

(updated in 2017)

“Trans fat produced by partial hydrogenation of fats and oils should be considered industrial food additives having

no demonstrable health benefits and clear risks to human health…

as such, food services, restaurants, and food and cooking fat manufacturers should avoid their use"

– WHO Scientific update on health consequences of trans fat

– recommended by the Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases

Triggering action at local level through urban governance for health and well-being

Improved health status and well-being of 22 million people through participatory and multisectoral urban governance by 2028

“Health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life; where they learn, work, play, and love.”

– Ottawa Charter

Bogotá will become “the Caring City” by promoting an inclusive, sustainable, conscious city for population well-being through a participatory approach. The approach to primary health care will be strengthened by intersectoral mechanisms and strategies, and fostering collaboration among academia, civil society, city sectors such as health, social innovation, planning and development.

Bogotá will become “the Caring City” by promoting an inclusive, sustainable, conscious city for population well-being through a participatory approach. The approach to primary health care will be strengthened by intersectoral mechanisms and strategies, and fostering collaboration among academia, civil society, city sectors such as health, social innovation, planning and development.

WHO creates a

network of 5 committed mayors of cities

with shared interest in access to health-care services, informal and peri-urban settlements and social cohesion and engagement

Healthy cities corporate approach highlights urban governance for

health and well-being as an essential domain for healthy cities

> 100 mayors committed

to advancing health and sustainable urban development by integrating 10 action areas into implementation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda

– Shanghai Consensus on Healthy Cities as proposed by WHO

Communities and civil society participation at the centre of health promotion | Urbanizationas a key influence on health |

– key commitments of the Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World

Active participation of all sectors and civil society

in implementation of health-promoting actions

– key action in Mexico Ministerial Statements for the Promotion of Health: From Ideas to Action

Increased community participation and individual empowerment

are key priorities for health promotion

– Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century

WHO European Healthy Cities Network started and Helsinki, Finland, promoted health in all policies

Title goes here

Subtitle goes here, with any format

Text goes here

Text goes here

Title here

Main text here.Main text here.Main text here.Main text here.

Title here

Main text here.Main text here.Main text here.Main text here.

Text inside box goes here.Text inside box goes here.Text inside box goes here.

Text inside box goes here.Text inside box goes here.Text inside box goes here.

Main text goes here

Other formatted text, centered

Main text goes here

Other formatted text, centered

Main text goes here

Main text goes here