Last month, the World Health Organization (WHO) marked its 75th anniversary, at a time when strong global health leadership is critical. Urgent new challenges, hardly heard of 75 years ago, now pose pressing threats, and cross-border concerns call for a collective response. This feature story looks at WHO’s leadership in facing the 21st century crises of antimicrobial resistance and climate change, and driving a revamp of mental health for today’s needs. Groundbreaking progress in long-standing areas of work, such as tuberculosis and malaria, is also covered, as well as how WHO is transforming for the 21st century and harnessing today’s technology. Despite these changes, “Health for All” is still a core value and the theme for WHO’s 75th anniversary.

Leading the fight against antimicrobial resistance

When WHO was founded in 1948, a golden era of antibiotics was beginning, promising a future of “miracle medicines” able to cure deadly diseases. Today, that future is in jeopardy with the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Drug-resistant bacteria kill an estimated 1.3 million people globally every year and are at alarming levels in many countries. The global problem of AMR can occur anywhere and does not respect borders. Without urgent action, AMR could unravel the gains of modern medicine.

With such high stakes, WHO has drawn on its mandate as the leading directing and coordinating authority in health to drive action, raise global awareness, and set guidelines and priorities. Today, 170 countries have national action plans on AMR and 127 countries are enrolled in WHO’s global surveillance system that tracks where and how AMR is increasing and informs strategies. The new AWaRe antibiotic book promotes appropriate use of antibiotics and is based on WHO’s AWaRe classification to contain AMR. WHO also helps set research priorities by analysing the antibiotic pipeline while the Global Leaders Group is galvanizing political momentum.

.jpg?sfvrsn=4ec67766_3) Daniel Hakobyan, 4, was given three different types of antibiotics for persistent fever in a hospital in Yerevan, Armenia, although antibiotics are not effective for the condition he had - multisystem inflammatory syndrome. WHO is supporting Armenia to improve the rational use of antibiotics. Credit: WHO / Nazik Armenakyan.

Daniel Hakobyan, 4, was given three different types of antibiotics for persistent fever in a hospital in Yerevan, Armenia, although antibiotics are not effective for the condition he had - multisystem inflammatory syndrome. WHO is supporting Armenia to improve the rational use of antibiotics. Credit: WHO / Nazik Armenakyan.

As the drivers of AMR also lie in the animal, plant, food and environment sectors, WHO has jointly forged a cross-sectoral “One Health” response with relevant international agencies in the Quadripartite, establishing a joint plan of action and partnership platform in 2022. Also in 2022, ground-breaking targets to address AMR across the animal, farming and human health sectors were set, and the first list of fungal “priority pathogens” published. Despite these efforts, far more commitment and concrete action are needed to combat the “silent pandemic” of AMR.

Highlighting health challenges of climate change

In WHO’s early years, climate science barely existed. Today, climate change is recognized as the single biggest threat to humanity. It impacts health in myriad ways, such as through heat stress, increased infectious diseases and food production. WHO has used its convening and technical strengths to mobilize a collective health voice, gather evidence and support countries to increase health resilience to climate risks.

Emphasizing that the climate crisis is a health crisis, WHO has underlined the health benefits of cutting fossil fuel use, such as reducing the 7 million deaths caused by air pollution. In 2018, WHO hosted the first global conference on air pollution and health. WHO has also highlighted the need to strengthen protection against escalating climate-induced health threats, from heatwaves to increasing cholera outbreaks.

At the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in 2021, WHO and partners built a stronger health focus and secured commitments from over 60 countries on resilient and low carbon health systems, which the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH) will support countries to deliver.

WHO’s support to countries in this field includes climate adaptation of health facilities, and their electrification with solar energy. A new platform, ClimaHealth, brings together health and climate information for collaborative work and WHO’s health and climate country profiles gather evidence on climate risks and tracks progress to address threats. Ultimately, the climate crisis requires a whole of society response, but strong collective action in health can lead the change.

Bringing mental health care into the community

When WHO was founded, humane mental health care barely existed – people suffered at home quietly or were sent to the “asylum”. Dramatic progress has since been made. Yet the unmet need for care is still huge (for example only 29% of people with psychosis receive care globally), with stigma, ignorance, and a lack of resources widely prevalent. This is why WHO made a clarion call for accelerated action in mental health, urging a move from isolated, custodial psychiatric institutions to comprehensive care in the community.

Through WHO’s leadership, mental health care and awareness are expanding. WHO’s Special Initiative for Mental Health, implemented in 9 countries, has increased mental health services to 5.2 million people, trained 6000 people and engaged with 450 partners. WHO’s World mental health report, one of the most downloaded WHO resources in 2022, offers a blueprint for transformation, with practical case examples and easy-to-use advice serving a vital need in countries where interventions barely exist. WHO’s QualityRights toolkit is helping ensure the quality of care and human rights standards, while its mhGAP Intervention Guide is key to the integration of mental health in primary health care and its “LIVE LIFE” guide covers key suicide prevention interventions.

WHO is also supporting countries in the midst of humanitarian crises to strengthen preparedness and to transform existing psychiatric services into community-based mental health systems. WHO’s extensive support in mental health to Ukraine has led to streamlined emergency-response efforts and a significant scale up of care – community mental health teams provided more than 23 000 consultations for severe mental disorders from February to December 2022.

.jpg?sfvrsn=6d7d385d_3)

Progress and challenges in combating communicable diseases

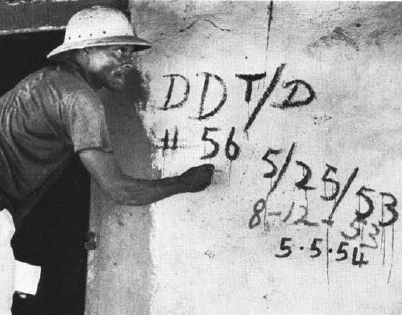

From the very start, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria were top concerns for WHO, named among “the Big Six” priorities at the first World Health Assembly in 1948. The insecticide DDT was then the weapon of choice to control malaria, while for TB, it was BCG vaccination and isolated clinics. These diseases are still among the most deadly infectious diseases, but control efforts have changed dramatically, with recent promising breakthroughs.

A new malaria vaccine (RTS,S) is saving lives: a substantial decrease in hospitalizations for severe malaria and a drop in deaths has been seen in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, where 1.4 million children have received the vaccine in a WHO-coordinated pilot programme. The fight against the pressing problem of drug-resistant TB advanced with new WHO guidelines for a groundbreaking all-oral treatment regimen that can significantly increase cure rates, and is cheaper, less toxic and three times shorter than traditional regimens.

Other infectious diseases widespread in WHO’s early days have been dramatically reduced, such as polio, yaws, trachoma and plague. Smallpox has been eradicated. Concerted efforts in the last decade have seen more neglected tropical diseases eliminated – in 2022, trachoma was certified as eliminated in 4 more countries and sleeping sickness in 3 countries. Guinea worm cases fell to just 13 in 2022. A new network, “GONE”, aims to ensure river blindness will soon be gone.

But some diseases are more intractable to control. Cholera, which has long held international health focus, dating back to the cholera pandemics of the 19th century, still persists with poverty and is rising with climate change – in 2022, 30 countries reported a 50% increase in cases from 5 years ago, to which WHO responded with large-scale vaccination campaigns, cholera kits for half a million people and a supply coordination mechanism. Influenza outbreaks, and a possible pandemic threat, were always a concern: 70 years ago, the Global Influenza Surveillance And Response System was set up. This global network, with strong collaboration and laboratories in 127 countries, was heavily leveraged during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has laid bare the need for greater pandemic preparedness.

Transforming for the 21st century

In the last several years, WHO has embarked on an ambitious transformation agenda to make it more agile, innovative, results-focused and fit-for-purpose in the 21st century. Some of the changes made, such as bolstering partnerships and science, proved to be invaluable during the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw WHO engaging in unparalleled partnerships for countermeasures, tools and research. WHO also adopted a new strategy with the ambitious “Triple Billion” targets, which are aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and provide a measurement framework to track the progress of Member States and the WHO Secretariat towards achieving these targets.

Cognizant of the changing world, WHO has helped promote gender and disability inclusion. Today, one in six people experience disability, in part due to a growing burden of noncommunicable diseases, yet many experience unacceptable inequities, as a new WHO global report shows.

WHO is also working to harness the power of digital technologies – in mobile phones, telemedicine or digital information – to transform health. In 2022, WHO trained over 600 national digital health leaders in 100 countries. Enrolments in WHO’s award-winning online learning platform for health emergencies have surged by 4000% in 2.5 years, with 7.5 million learners in the last three years.

The right to health has long been a WHO principle: it is enshrined in its constitution. Today, health equity is key to addressing future health challenges. WHO is urging countries to scale up primary health care as a bridge to universal health coverage, a triple billion target. WHO continues to fight for everyone, everywhere, to have access to quality health care in its vision of health for all.