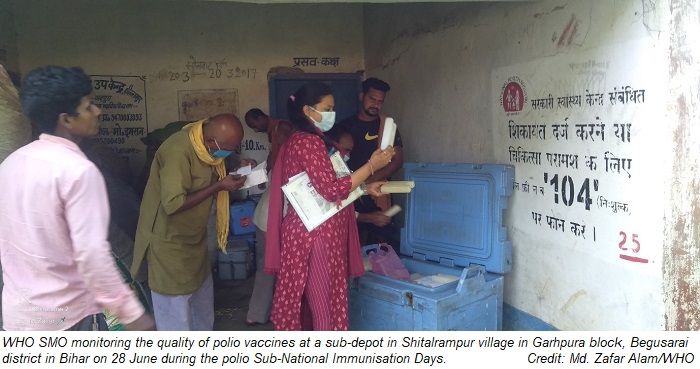

Dr Geetika Shankar gets up at 03:15 in the morning to leave home in the Begusarai district of Bihar to visit an ice factory, where she monitors the quality of ice packs used to store the vaccine at a viable temperature. This is followed by a visit to the primary health care “cold chain points”, where bivalent polio vaccine vials are packed in vaccine carriers and distributed to vaccination teams and supervisors to begin Sub-National Immunisation Days (SNIDs).

Dr Shankar, a WHO Surveillance Medical Officer (SMO), works in the Begusarai, Lakhisarai and Sheikhpura districts in Bihar. She is one among the 28 SMOs in Bihar supporting Sub-National Immunisation Days (SNIDs) in June in select districts that remain vulnerable to polio. In her districts, SNIDs were organised from 27 June to 5 July 2021, which included 5 days of house-to-house mop-up vaccination activity, two days of “B Team” visits to houses marked “X” to reach missed children, and one day of street survey.

The last polio case was reported in India over a decade ago in January 2011, but the Government of India is continuing to vaccinate all children under 5 years by organising a round of National Immunisation Days across the country, and two SNIDs in select states and districts vulnerable to polio, as per the recommendations of India Expert Advisory Group for polio eradication.

Reaching every child in every home across the state of Bihar requires meticulous planning, training, supply of vaccine and logistics, maintaining cold chain at all levels and close monitoring of the activities.

WHO teams are supporting advocacy, microplanning and trainings of thousands of vaccinators in each district, which is followed by monitoring of vaccination, both at the site and through house-to-house surveys to ensure no child gets left behind.

“I usually follow the last vehicle moving from cold-chain points to reach the sub-depot, where I monitor sub-depot level distribution and identify teams and supervisors arriving late, which leads to critical delays in beginning the vaccination rounds. I return home at around 07:30 to cook and bathe and feed my two-year-old daughter. The nanny arrives at 09:00, and I leave home again by 09:15 to begin house-to-house monitoring and the monitoring of monitors,” said Dr Shankar.

Lunch is usually on the go, with Dr Shankar usually carrying half a dozen bananas or apples for herself and the driver. After a briefing session at around 17:30 with the district immunisation officer, she comes back home at around 19:00 in the evening.

She is out longer on days she visits the neighbouring districts of Lakhisarai and Sheikhpura. “I left for Sheikhpura for monitoring on 30 June and returned home late at night. In Lakhisarai, polio vaccination was suspended for two days to continue with COVID-19 vaccination, so I had to stay there for two nights. It’s tough being away from my daughter, but the work I do will give other children a healthier and happier future,” said Dr Shankar.

“I am on my feet all day for SNID monitoring, which is exhausting. I am forever grateful to my supervisors, husband and colleagues, including office drivers, for supporting me to work and look after my daughter,” she said.

“I miss my daily Yoga sessions and compromise on sleep in the run-up and the roll-out of the SNIDs, but when I see healthy children running and laughing around me, it makes it all worth it,” said Dr Shankar.