Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests recommended for use in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis

Circulating microfilariae can be detected by examining thick smears (20–60 μl) of finger-prick blood. Blood must be collected at a specific time – either at night or during the day – depending on the periodicity of the microfilariae. The method is inexpensive and feasible at individual and community levels for mapping the endemicity of lymphatic filariasis and monitoring mass drug administration (MDA).

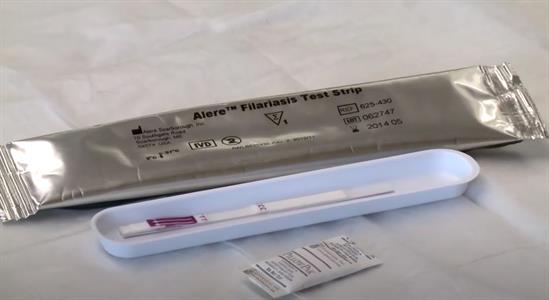

The Alere Filariasis Test Strip (FTS) is a rapid diagnostic test recommended for mapping, monitoring and transmission assessment surveys (TAS) for the qualitative detection of Wuchereria bancrofti antigen in human blood samples. The FTS has replaced the Binax Now filariasis immunochromatographic test (ICT), which also detects the same antigen in blood samples. The Brugia Rapid point-of-care cassette test (BRT) manufactured by Reszon Diagnostics is recommended for use during TAS to detect IgG4 antibody against Brugia spp. in human blood samples.

Read the Filariasis Test Strip (FTS) Bench Aid. This bench aid provides detailed instruction on the proper use of the new Filariasis Test Strip used for the detection of Wuchereria bancrofti antigen.

Other diagnostic tools

Microfilariae DNA can be detected in human blood and in mosquitoes through laboratory-based methods using PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). Efforts are ongoing to validate the use of new rapid diagnostic tests targeting antibodies in population-based surveys for programmatic use in post-MDA surveillance. Methods for identifying infection in mosquitoes are available and are being used in some settings as an indirect, non-invasive way to monitor the continued presence of infection in communities.

Bench Aids for the diagnosis of filarial infections

The microfilariaAt the light-microscopic level and with the aid of a variety of stains, a microfilaria appears Fig. 1 Typical microfilaria as a primitive...

Clinical forms

The prevalence of filarial infection in children has become better understood in recent years. Whereas the disease was once thought to affect only adults, it now appears that most infections are acquired in childhood. Initial infection is followed by a long period of subclinical disease, which progresses in later life to clinically manifest disease.

Acute attacks

The adult filarial worms cause inflammation of the lymphatic system, resulting in lymphangitis and lymphadenitis. These conditions lead to lymphatic vessel damage, even in asymptomatic people, and lymphatic dysfunction, which predispose the lower limbs in particular to recurrent bacterial infection. These secondary infections provoke adenolymphangitis (ADL), commonly called “acute attacks”, which are the commonest symptom of lymphatic filariasis and play an important role in the progression of lymphoedema. It has been suggested that bacteria commonly gain access to damaged lymphatic vessels through “entry lesions”, often between the toes. ADL, which resembles erysipelas or cellulitis, is associated with local pain and swelling and with fever and chills.

Lymphoedema and elephantiasis

Lymphoedema and its more advanced form, elephantiasis, occur primarily in the lower limbs and are commoner in women. Several factors have been implicated in the progression of lymphoedema, including repeated episodes of ADL. Although lymphoedema due to filariasis should be distinguished from conditions such as heart failure, malnutrition, venous disease, podoconiosis and HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma, there is no agreement on its classification. In its most advanced form, elephantiasis may prevent people from carrying out their normal daily activities.

Hydrocoele

Scrotal hydrocoele is due to accumulation of fluid in the cavity of the tunica vaginalis. It has been suggested that true filarial hydrocoele occurs after the death of adult filarial worms, while a chylocoele is due to accumulation of fluid after the rupture of lymphatic vessels in the scrotal cavity.

Other diseases related to lymphatic filariasis

Podoconiosis

A type of tropical lymphoedema, podoconiosis results from a genetically determined abnormal inflammatory reaction to mineral particles in irritant red clay soils derived from volcanic deposits. It is mostly found in highland areas of tropical Africa, Central America and north-west India. It is a non-parasitic disease and, like lymphatic filariasis, results in impairments due to lymphoedema. As is the case for lymphatic filariasis, a basic package of care can alleviate suffering and prevent further progression of disease and disability.

Treatment

Endemic communities

The primary goal of treating affected communities is to eliminate microfilariae from the blood of infected individuals in order to interrupt transmission of infection by mosquitoes. Studies have shown that > 5 years of MDA with preventive chemotherapy reduces microfilariae from the bloodstream and prevents the spread of microfilariae to mosquitoes. Preventive chemotherapy involves a combined dose of two medicines given annually to an entire at-risk population as follows: albendazole (400 mg) plus ivermectin (150–200 μg/kg) or diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) (6 mg/kg). MDA with albendazole (400 mg) alone should be given preferably twice per year to stop the spread of lymphatic filariasis in areas where Loa loa is present.

Individuals

All people with filariasis who have microfilaraemia or a positive antigen test should receive antifilarial drug treatment to eliminate microfilariae. Unfortunately, the medicines available have limited effect on adult worms. Infected patients can be treated with one of the following regimens:

- a single dose of a combination of albendazole (400 mg) with ivermectin (150–200 μg/kg) in areas where onchocerciasis is co-endemic; in areas where onchocerciasis is non co-endemic, either

- a single dose of a combination albendazole (400 mg) plus diethylcarbamazine (6 mg/kg) or

- DEC (6 mg/kg) alone for 12 days.

Managing morbidity and preventing disability

Management of morbidity and disability prevention (MMDP) in lymphatic filariasis require a broad strategy involving both secondary and tertiary prevention. Secondary prevention includes simple hygiene measures, such as basic skin care and exercise, to prevent ADL and progression of lymphoedema to elephantiasis. For management of hydrocoele, surgery may be appropriate. Tertiary prevention includes psychological and socioeconomic support for people with disabling conditions to ensure that they have equal access to rehabilitation services and opportunities for health, education and income. Activities beyond medical care and rehabilitation include promoting positive attitudes towards people with disabilities, preventing the causes of disabilities, providing education and training, supporting local initiatives, and supporting micro- and macro-income-generating schemes. The activities can also include education of families and communities to help patients with lymphatic filariasis to fulfil their roles in society. Thus, vocational training and appropriate psychological support may be necessary to overcome the depression and economic loss associated with the disease. MMDP must be continued in endemic communities after MDA has stopped and after validation, as chronically affected patients are likely to remain in these communities.