1.4 National TB prevalence surveys

Rationale: why are surveys needed?

To reliably track the burden of tuberculosis (TB) disease in terms of TB incidence and TB mortality from subnational to global levels, the ultimate goal is that all countries can rely on data routinely collected through a) national disease surveillance systems and b) vital registration (VR) systems in which causes of death are coded according to the international classification of diseases (ICD).

Currently, all countries have national systems for notification (i.e. reporting) of people diagnosed with TB and almost all countries report TB case notification data to the World Health Organization (WHO) on an annual basis (Section 2.1). However, in many countries (including most high TB burden countries) the number of notified cases each year is not a good proxy for the actual number of people who develop TB disease, for two reasons. The first is underreporting of people diagnosed with TB, especially in countries with large private sectors or in which people with TB seek care in public facilities that are not linked to the national TB programme and its associated reporting systems. The second is underdiagnosis, especially in countries with geographic or financial barriers to seeking health care. Many countries (including most high TB burden countries) do not have established national VR systems of high quality and coverage that can be used to reliably monitor the number of deaths and their cause (1).

In countries with a relatively high burden of TB disease that do not yet have national disease notification systems or national VR systems with cause-of-death data that are of sufficiently high quality and coverage, national TB prevalence surveys are the best way to directly measure the burden of TB disease in the population (2–4). In terms of disease burden, WHO currently recommends consideration of surveys according to previously documented epidemiological criteria (3, 4).

What is measured in a survey?

National TB prevalence surveys can provide a reliable measurement of the number of people in the population with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB at a given point in time, and the distribution of these cases by age and sex. In addition, repeat surveys allow assessment of trends, and of the impact of interventions to reduce the burden of disease in the period since the last survey. WHO recommends that surveys focus on people aged 15 years or over (2).

How can survey results be used?

Results can be used to inform national estimates of TB incidence in all age groups, and can thus help to track progress towards the milestones and targets for reductions in TB incidence set in the End TB Strategy (Section 1.1). Previously, survey results were also important for the assessment of progress towards global, regional and national targets for reductions in TB prevalence between 1990 and 2015.

For these reasons, the implementation of national TB prevalence surveys in 22 priority countries (referred to as global focus countries, GFCs) was one of three strategic areas of work defined by the WHO Global Task Force on TB Impact Measurement (the Task Force) for the period 2007–2015 (2, 3). National TB prevalence surveys were retained within the Task Force’s updated strategic areas of work after 2015 (4, 5).

Other benefits of prevalence surveys include that they can be used to document health care seeking behaviour in the public and private sectors, assess variation in underreporting or underdiagnosis of TB by age and sex (using the ratio of prevalence to notifications), and quantify the extent of underreporting of people diagnosed with TB to national authorities. Findings can help to inform the development or improvement of TB case finding, diagnosis and treatment interventions.

Status of progress

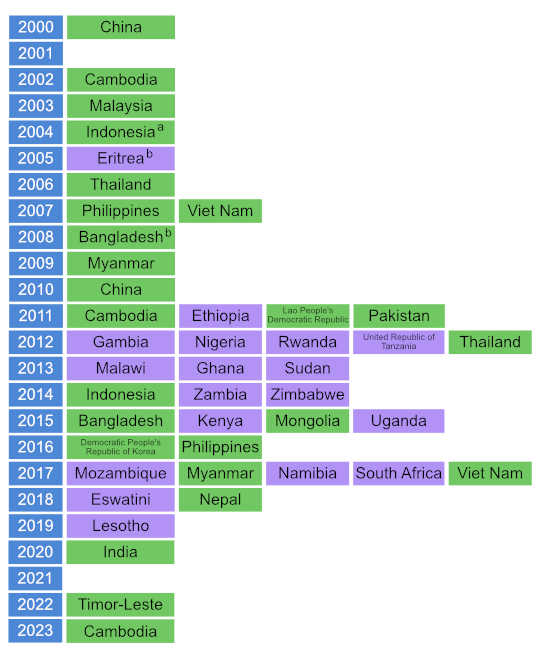

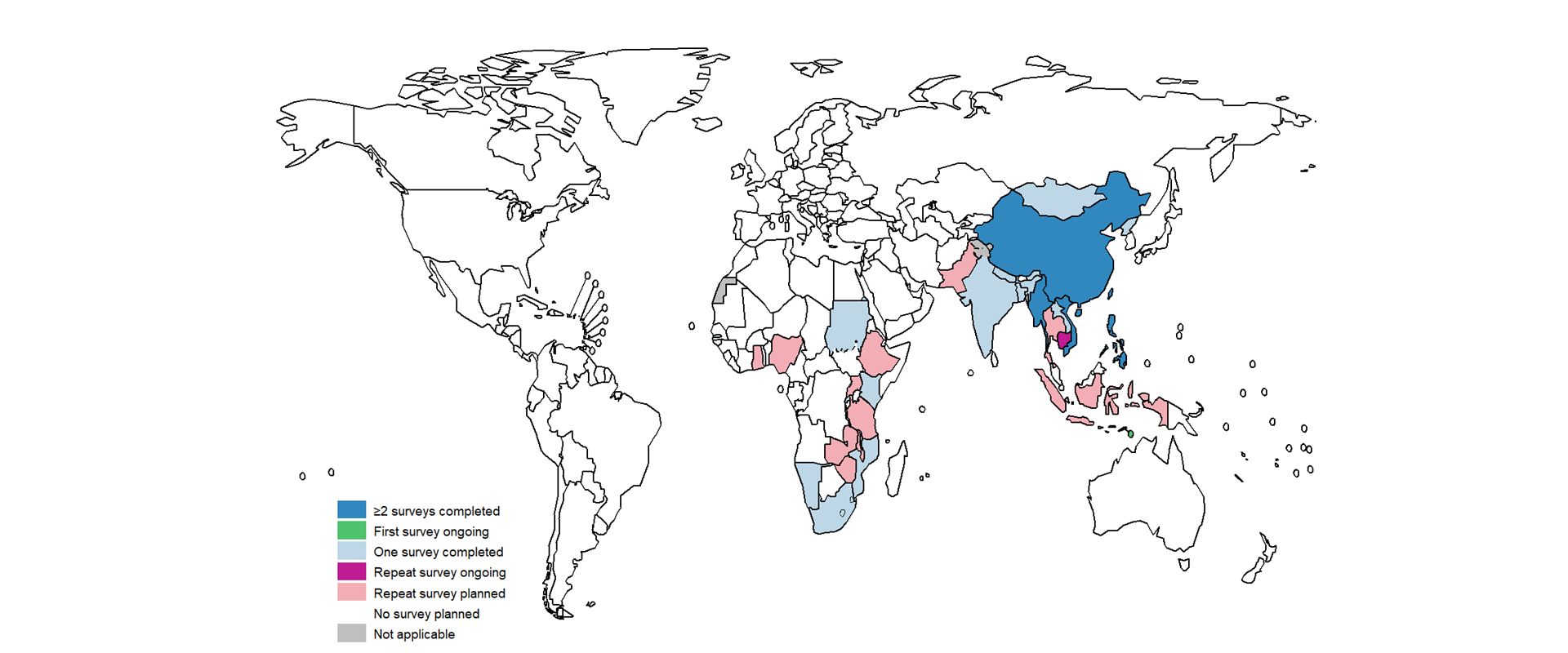

Between 2000 and August 2023, a total of 43 national TB prevalence surveys in 34 countries were implemented; of these, 40 used the screening and diagnostic methods recommended by WHO (Fig. 1.4.1). These 34 countries comprised 18 in Africa and 16 in Asia, and 20 of the 22 GFCs. Five countries implemented repeat surveys: China, Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Viet Nam. Timor-Leste started its first survey in December 2022, and Cambodia started its third survey in July 2023 (Fig. 1.4.2).

A growing number of countries are actively interested in implementing a repeat prevalence survey in the next 1–3 years: Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe in Africa; and Indonesia, Pakistan and Thailand in Asia.

b The surveys in Bangladesh (2008) and Eritrea (2005) collected sputum samples from all individuals (aged ≥15 years), and did not use chest X-ray and/or a symptom questionnaire to screen individuals for sputum submission.

Survey findings and implications

In African countries, prevalence ranged from 119 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 79–160) per 100 000 population in Rwanda (in 2012) to 852 (95% CI: 679–1026) per 100 000 population in South Africa (in 2017). In Asian countries, prevalence ranged from 119 (95% CI: 103–135) per 100 000 population in China (in 2010) to 1159 (95% CI: 1016–1301) per 100 000 population in the Philippines (in 2016).

In most Asian countries and some African countries, prevalence increased with age (Fig. 1.4.4, Fig. 1.4.5).

As transmission declines, more incident cases arise from old (remote) rather than recent infection. Therefore, a pattern in which prevalence increases with age suggests that transmission is falling. It is encouraging that prevalence surveys indicated that transmission is potentially declining in many Asian countries and in several African countries (e.g. Ghana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and the United Republic of Tanzania). Elsewhere, surveys suggested considerable community transmission; peaks in many African countries in the age groups 35–44 or 45–54 years also reflect the impact of the HIV epidemic.

A striking finding across all surveys was the much higher burden of TB disease in men compared with women (Fig. 1.4.6). The male to female (M:F) ratio of bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary cases in surveys completed in 2007–2019 ranged from 1.2 (in Ethiopia) to 4.5 (in Viet Nam); in most countries it was in the range 2–4. These findings mean that men typically account for about 66–75% of the burden of TB disease in adults.

Ratios of prevalence to notifications (P:N, expressed in years) suggest marginally higher detection and reporting gaps in Asia compared with Africa, and lower detection and reporting gaps among women compared with men (Fig. 1.4.7, Fig. 1.4.8). The combination of a higher disease burden in men and larger gaps in detection and reporting indicates a need for strategies to improve access to and use of health services among men (6).

A large proportion of survey participants with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB did not report symptoms during screening and were only tested for TB based on chest X-ray screening. This proportion was higher in Asian countries compared with African countries, and varied from 30% in Malawi to 86% in Myanmar (Fig. 1.4.9). The natural history of these individuals, their contribution to overall transmission on a population level, and implications for case-finding and treatment needs further exploration (7, 8).

For more information

A WHO 2021 publication provides full details about the results and lessons learned from the 25 national surveys implemented in 2007–2016 (3). In addition, regional syntheses of survey results and lessons learned are available in journal articles (9, 10).

A document has been published in May 2023 that discusses the diagnostic algorithms to be used in future surveys (implemented from 2023 onwards) (11). It provides the basis for recommendations on diagnostic algorithms to be included in the third edition of WHO guidance on national TB prevalence surveys which is scheduled for completion in 2023.

References

Mikkelsen L, Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, Setel PW, de Savigny D, Lozano R et al. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1395-406 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25971218).

Tuberculosis prevalence surveys: a handbook (WHO/HTM/TB/2010.17). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44481).

National tuberculosis prevalence surveys, 2007-2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341072).

World Health Organization Global Task Force on TB Impact Measurement. Report of the sixth meeting of the full Task Force; 19-21 April 2016, Glion-sur-Montreux, Switzerland. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 (https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/hq-tuberculosis/global-task-force-on-tb-impact-measurement/meetings/2016-05/tf6_report.pdf?sfvrsn=8a9563a3_3).

Fact sheet on the WHO Global Task Force on TB Impact Measurement (May 2023). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/WHO-UCN-TB-2023.2).

Horton KC, MacPherson P, Houben RM, White RG, Corbett EL. Sex differences in tuberculosis burden and notifications in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002119 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27598345).

Kendall EA, Shrestha S, Dowdy DW. The Epidemiological Importance of Subclinical Tuberculosis. A Critical Reappraisal. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Jan 15;203(2):168-174. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2394PP. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33197210/).

Richards AS, Sossen B, Emery JC, Horton KC, Heinsohn T, Frascella B et al. Quantifying progression and regression across the spectrum of pulmonary tuberculosis: a data synthesis study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023 May;11(5):e684-e692. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00082-7. Epub 2023 Mar 23. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36966785/).

Onozaki I, Law I, Sismanidis C, Zignol M, Glaziou P, Floyd K. National tuberculosis prevalence surveys in Asia, 1990-2012: an overview of results and lessons learned. Trop Med Int Health. 2015 Sep;20(9):1128-1145 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25943163).

Law I, Floyd K, African TB Prevalence Survey Group. National tuberculosis prevalence surveys in Africa, 2008-2016: an overview of results and lessons learned. Trop Med Int Health. 2020 Nov;25(11):1308-1327 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32910557).

National tuberculosis prevalence surveys: what diagnostic algorithms should be used in future? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/367909).