/social-determinants-of-health-(sdh)/equity-and-health-(eqh)/indonesia-immunization-heroes.tmb-768v.jpg?sfvrsn=8f5ac70b_1)

World report on social determinants of health equity, 2025

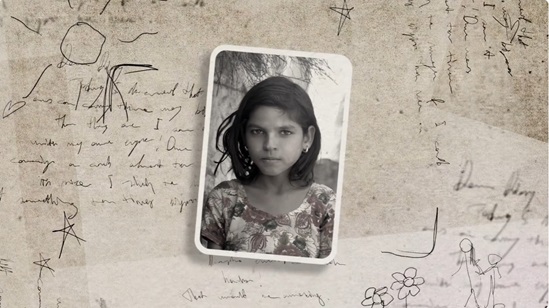

Children at State Elementary School 24 on Pala Island, Indonesia, raise their hands to answer a question during a health and immunization outreach session. Pala Island, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

Preventable life expectancy gaps are worsening across social groups, which are cutting lives short, sometimes by decades.

Where we are born, grow, live, work and age, and our access to power, money and resources influence our health outcomes more than genetic influences or healthcare. For instance, if we live in a neighborhood with limited access to quality housing, education, and job opportunities, we have a higher risk of illness and death. These are known as social determinants of health equity – the non-medical root causes of ill health.

World report on social determinants of health equity

Launched on 6 May 2025, the WHO World report on social determinants of health equity confirms that our health and well-being depends on much more than our genes and access to health care. To reduce these avoidable and unjust health gaps we must address the non-medical root causes that shape most of our health and well-being.

The report builds on the report of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (2008), as requested by World Health Resolution 74.16.

Key messages

Health equity around the world

Spread the word about health equity

Technical resources

/social-determinants-of-health-(sdh)/equity-and-health-(eqh)/wrsdhe-report-gif.gif?sfvrsn=24345f08_3)

/social-determinants-of-health-(sdh)/equity-and-health-(eqh)/recommendations-wrsdhe.tmb-1920v.png?sfvrsn=1b411317_1)

/social-determinants-of-health-(sdh)/equity-and-health-(eqh)/action-areas-wrsdhe.tmb-1920v.png?sfvrsn=d7dfa0f5_2)

/social-determinants-of-health-(sdh)/equity-and-health-(eqh)/recommendations2-wrsdhe.tmb-1920v.png?sfvrsn=6d42e850_1)