Situation at a glance

Description of the situation

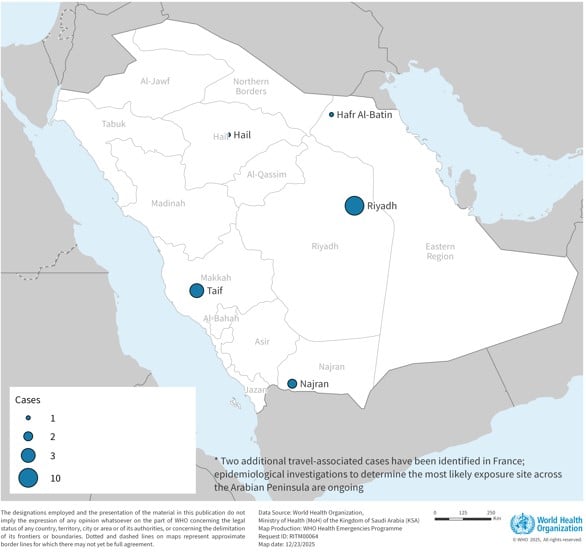

Since the first report of MERS-CoV in the KSA and Jordan in 2012, a total 2635 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection, with 964 associated deaths (Case Fatality Ratio (CFR) of 37%), have been reported to WHO from 27 countries, across all six WHO regions (Figure 1). The majority of cases (84%; n=2224), have been reported from the KSA (Figure 2). Since the beginning of 2025 and as of 21 December, a total of 19 cases have been reported to WHO. Overall, 17 cases were reported in the KSA from five regions named: Riyadh (n=10), Taif (n=3), Najran (n=2), Hail (n=1), and Hafr Al-Batin City (n=1) (Figure 3). In addition, two travel associated cases of MERS-CoV infection have been reported in France, with likely exposure occurring during recent travel in the Arabian Peninsula (Figure 3).

This disease outbreak news report focuses on the recent nine cases of MERS-CoV infection reported between 4 June - 21 December 2025: seven cases from the KSA and the two imported cases to France. The details of cases reported earlier in 2025 can be referred to in the previously published disease outbreak news on 13 March 2025 and 12 May 2025.

Between 4 June and 21 December 2025, the MoH of the KSA reported a total of seven cases of MERS CoV infection. The cases were reported from three regions: Najran (2), Riyadh (3), and Taif (2). No epidemiological links were identified between the seven cases. In addition, between 2 and 3 of December 2025, the IHR NFP for France reported two cases of MERS – CoV with recent travel to the Arabian Peninsula during the month of November.

Follow-up has been completed for all contacts and no secondary infections have been identified or reported. From September 2012, France has recorded a total of four laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection, including one death: two cases were reported in 2013, and the latest two cases in December 2025. All cases had been travelers exposed in the Arabian Peninsula and returning back to France.

For additional details please see Table 1.

Figure 1: Epidemic curve of MERS-CoV infections (2635) and deaths (964) reported globally between 2012-2025

Figure 2: Epidemic curve of MERS-CoV infections (2224) and deaths (868) reported in KSA between 2012-2025

Figure 3. Geographical distribution of MERS-CoV infections between 1 January and 21 December 2025 (n=19).

Table 1: MERS-CoV cases reported by KSA and France between 4 June and 21 December 2025

Epidemiology

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The case fatality ratio (CFR) among confirmed cases is around 37%. The CFR is calculated based solely on laboratory-confirmed infections and may overestimate the actual mortality rate since milder cases often go undetected or unreported.

Humans can contract MERS-CoV through multiple transmission pathways; the primary route being through direct or indirect contact with dromedary camels, which serve as the virus’s natural host and primary zoonotic reservoir. Additionally, human-to-human transmission can occur via infectious respiratory particles primarily in close-contact situations and can also occur through direct or indirect contact; this is especially prominent in health-care settings. Human-to-human transmission of the virus has occurred in health care facilities in several countries, including transmission from patients to health care providers and transmission between patients before MERS-CoV was diagnosed. It is not always possible to identify patients with MERS‐CoV early or without testing because symptoms and other clinical features may be non‐specific. Outside these environments, there has been limited documented human-to-human transmission.

MERS can present with no symptoms (asymptomatic), mild symptoms (including mild respiratory issues), or severe illness leading to acute respiratory distress and death. Common symptoms include fever, cough, and breathing difficulties, with pneumonia frequently observed, though not always present. Some patients also experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea. Severe cases may require intensive care, including mechanical ventilation. Those at higher risk of severe outcomes include older adults, individuals with weakened immune systems, and those with chronic conditions like diabetes, kidney disease, cancer, or lung disorders.

The number of MERS-CoV infections reported to WHO substantially declined since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, this was likely the result of epidemiological surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 being prioritized. Similar clinical pictures of both diseases may have resulted in reduced testing and detection of MERS-CoV infections. However, the MoH of the KSA has been working to improve testing capacities for better detection of MERS-CoV since the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic, with MERS-CoV included into sentinel surveillance testing algorithms since the second quarter of 2023, for samples that test negative for both influenza and SARS-CoV-2. In addition, recommended IPC measures (e.g., mask-wearing, hand hygiene, physical distancing, improving ventilation) and public health and social measures in the community to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, (stay-at-home orders, reduced mobility) also likely reduced onward human-to-human transmission of respiratory infections including MERS-CoV. Potential cross-protection conferred from infection with or vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 and any reduction in MERS-CoV infection or disease severity and vice versa has been hypothesized but requires further investigation. [1,2]

Public health response

WHO is supporting Member States in strengthening preparedness and response.

Activities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia include;

- Strengthened surveillance with immediate notification of all suspected and confirmed cases.

- Strict implementation of infection prevention and control transmission-based precautions (Contact and Droplet precautions) in healthcare facilities for suspect or confirmed patients, and airborne precautions for patients undergoing aerosol-generating procedures.

- Identification of health and care worker contacts and perform risk assessment of their exposure, considering the timely identification of symptomatic patients, implementation of IPC measures, and correct utilization of PPE while treating patients,

- Exposed health and care workers are followed up for 14 days to monitor symptoms. If they develop symptoms, they are to be removed from working with patients until tested and symptoms are fully resolved.

- Patients exposed to MERS-CoV in the healthcare setting must be tested to determine their ability to continue working with patients without further transmission, which could potentially lead to outbreaks in the healthcare facility.

- Identification of all potential community contacts and active follow-up to monitor symptoms for 14 days.

- All community acquired cases are investigated for having direct or indirect contact with camels or their products.

- Cases linked to camel exposures are notified to the National Center for Prevention and Control of Plants, Pests, and Animal Diseases (Weqaa) to investigate potential camel sources.

- Camels identified as a presumed source are quarantined and tested for MERS-CoV, and if live virus is detected, the quarantine period will be extended until live virus is no longer detected in camel.

Activities in France include;

- On 4 December 2025, MoH France published information regarding the two imported cases of MERS-CoV in the country (link).

- Genomic sequencing was conducted from the first case and reported as being the same lineage that is circulating in the Arabian Peninsula. Further laboratory analyses are ongoing.

- Contact tracing was initiated as soon as the first case was detected for the monitoring and surveillance of fellow travellers and co-exposed individuals, high-risk contacts, and hospital contacts. It was completed in week 51 and no additional cases among the travellers have been reported, nor any secondary cases as of 19 December 2025.

- Asymptomatic co-exposed individuals and at-risk contacts located in France were offered a full testing protocol (nasopharyngeal swab, sputum, rectal swab and serology) on a voluntary basis up to 29 days after their last exposure, even if they did not exhibit any symptoms.

WHO risk assessment

As of 21 December 2025, a total of 2635 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection have been reported globally to WHO, with 964 associated deaths. The majority of these cases have occurred in countries on the Arabian Peninsula, including 2224 cases with 868 related deaths (CFR 39%) reported from the KSA.

A notable outbreak outside the Middle East occurred in the Republic of Korea, in May 2015, during which 186 laboratory-confirmed cases (185 in the Republic of Korea and 1 in China) and 38 deaths were reported. However, the index case in that outbreak had a history of travel to the Middle East.

Three limited healthcare-related clusters have recently been reported from the KSA, two in 2024 comprised of three and two cases each, and one in 2025 comprised of 7 cases; the previous cluster before that had been observed in May 2020, also in the KSA. Extensive contact tracing was applied in the 2025 cluster, which lead to detection of four asymptomatic and two mild cases, who fully recovered. Despite these recent clusters, zoonotic spillover remains an important mode of human infection, leading to isolated cases and limited onwards transmission between humans.

Global total cases reflect laboratory-confirmed cases reported to WHO under IHR (2005) or directly by Ministries of Health from Member States. These figures may underestimate the true number of cases if some were not reported to WHO, as they may be missed by current surveillance systems and not be tested for MERS-CoV – either due to similar clinical presentation as other circulating respiratory diseases or because infected individuals remained asymptomatic or had only mild disease. The total number of deaths includes those officially reported to WHO through follow-up with affected Member States.

The notification of these new cases does not change the overall risk assessment. WHO expects that additional cases of MERS-CoV infection will be reported from the Middle East and/or other countries where MERS CoV is circulating in dromedaries, and that cases will continue to be exported to other countries by individuals who were exposed to the virus through contact with dromedaries or their products (for example, consumption of raw camel milk, camel urine, or eating meat that has not been properly cooked), or in a healthcare setting. Due to the similarity of symptoms with other respiratory diseases that are widely circulating, like influenza or COVID-19, detection and diagnosis of MERS cases may be delayed, especially in unaffected countries, and provide an opportunity for onward human-to-human transmission to go undetected. WHO continues to monitor the epidemiological situation and conducts risk assessments based on the latest available information.

No vaccine or specific treatment is currently available, although several MERS-CoV-specific vaccines and therapeutics are in development. Treatment remains supportive, focusing on managing symptoms based on the severity of the illness.

WHO advice

Surveillance:

Based on the current situation and available information, WHO re-emphasizes the importance of strong surveillance by all Member States for acute respiratory infections, with the inclusion of MERS-CoV into the testing algorithm where warranted, and to carefully review any unusual patterns.

Clinical Management

The incubation period is typically 2-15 days (median 5 days), although prolonged incubation periods have been reported in the immunocompromised. Although mild disease does occur, clinicians should be aware that symptoms may frequently progress rapidly non-specific signs of upper respiratory tract infection, cough and breathlessness, to respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse.[3]MERS-CoV infection should be managed supportively with respiratory support titrated to the needs of the patient; there is a wide spectrum of severity, with many patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

The largest clinical trial in MERS compared a combination of lopinavir–ritonavir and interferon β-1b with placebo (95 patients).[4] Active treatment caused lower 90-day mortality in hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed MERS (90-day mortality of 48% and 29% respectively). Further analysis suggested a positive effect only in patients treated within 7 days of symptom onset. Although there is increasing use of corticosteroids for some respiratory conditions (specifically in COVID-19 and some other forms of pneumonia), their use in MERS-CoV is of uncertain benefit, and harms relating to their immunomodulatory effects may be significant; more data are needed. The use of convalescent plasma has not been proven, although has been used in a limited number of patients in a non-trial setting. While antibiotics have been used in severe disease to presumptively treat concurrent bacterial infection, there are no controlled data on efficacy. A retrospective analysis of 349 MERS patients examined macrolide antibiotic therapy. No difference in 90-day mortality was found in the 136 patients receiving macrolides compated with those who did not.[5]Infection prevention and control:

Human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV in healthcare settings has been associated with delays in recognizing the early symptoms of MERS-CoV infection, slow triage of suspected cases and delays in implementing timely IPC measures. IPC measures are therefore critical to prevent the spread of MERS-CoV in healthcare facilities and onwards in the community. Healthcare workers should always apply standard precautions consistently with all patients and perform risk assessments at every interaction in healthcare settings to determine the necessary protection measures. For patients with suspected MERS-CoV infection that require hospitalization, place patient in an adequately ventilated single room away from other patient care areas. In addition to standard precautions. Droplet and contact precautions should be implemented when providing care to patients with symptoms of acute respiratory infection who are suspects of any respiratory disease, including probable or confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection.[6,7]

Droplet and contact precautions should be maintained until the patient is no longer symptomatic (for at least 24 hours) and has two upper respiratory (URT) swabs (taken 24hrs apart) test negative in RT-PCR or according to local guidance. Additionally, airborne precautions should be applied when performing aerosol generating procedures or in settings where aerosol generating procedures are conducted. Early identification, case management and prompt isolation of suspected respiratory infected patients and cases, quarantine of contacts, together with appropriate IPC measures in health care settings, including improving ventilation in enclosed spaces and public health awareness can prevent the spread of human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV.

Public health and social measures:

MERS-CoV appears to cause more severe disease in people with underlying chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, renal failure, chronic lung disease, and immunosuppression. Therefore, people with these underlying medical conditions should avoid close contact with animals, particularly dromedaries, when visiting farms, markets, or barn areas where the virus may be circulating.

General hygiene measures, such as regular hand hygiene before and after touching animals or animal products and avoiding contact with sick animals, should be adhered to.

In addition, hygiene practices should be observed including the five keys to safer food should be followed when dealing with food items of camels; people should avoid drinking raw camel milk or camel urine or eating meat that has not been properly cooked.

WHO does not advise special screening at points of entry with regard to this event, nor does it currently recommend the application of any travel or trade restrictions.

Further information

- Infection prevention and control during health care for probable or confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection:interim guidance: updated October 2019. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/174652

- Transmission-based precautions for the prevention and control of infections: aide-memoire [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/356853.

- Standard precautions for the prevention and control of infections: aide-memoire.[cited 2025 Dec 10] Available from https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/356855

- MERS fact sheet, updated 11 December 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-(mers-cov)

- 2015 MERS outbreak in Republic of Korea [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/2015-mers-outbreak

- WHO MERS-CoV dashboard. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/mers

- Disease Outbreak News [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news

- EPI-WIN webinar: MERS-CoV, a circulating coronavirus with epidemic and pandemic potential - Pandemic preparedness, prevention and response with a One Health approach [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/24/default-calendar/epi-win-webinar-mers-cov-a-circulating-coronavirus-with-epidemic-and-pandemic-potential-pandemic-preparedness-prevention-and-response-with-a-one-health-approach

- MERS Outbreak Toolbox [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/outbreak-toolkit/disease-outbreak-toolboxes/mers-outbreak-toolbox

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) | Policy&Services : KDCA [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.kdca.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a30329000000

- Middle East respiratory syndrome: global summary and assessment of risk - 16 November 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MERS-RA-2022.1

- OpenWHO.org - Middle East respiratory syndrome [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://openwho.org/channel/Middle+East+respiratory+syndrome/574814

- Practical manual to design, set up and manage severe acute respiratory infections facilities [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/items/eb2cb9aa-ef45-4952-8307-a00cbeee70a6

- Strategic plan for coronavirus disease threat management: advancing integration, sustainability, and equity, 2025–2030 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240117662

- Update 88: MERS-CoV, a circulating coronavirus with epidemic and pandemic potential - Pandemic preparedness, prevention and response with a One Health approach [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/update-88-mers-cov-a-circulating-coronavirus-with-epidemic-and-pandemic-potential-pandemic-preparedness--prevention-and-response-with-a-one-health-approach

- WHO EMRO - MERS outbreaks [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/mers-cov/mers-outbreaks.html?format=html

References:

[1] AlKhalifah, J. M., Seddiq, W., Alshehri, M. A., Alhetheel, A., Albarrag, A., Meo, S. A., Al-Tawfiq, J. A., & Barry, M. (2023). Impact of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Viral Infection on Immunoglobulin-IgG Cross-Reactivity. Vaccines, 11(3), 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030552

[2] Zedan, H. T., Smatti, M. K., Thomas, S., Nasrallah, G. K., Afifi, N. M., Hssain, A. A., Abu Raddad, L. J., Coyle, P. V., Grivel, J. C., Almaslamani, M. A., Althani, A. A., & Yassine, H. M. (2023). Assessment of Broadly Reactive Responses in Patients With MERS-CoV Infection and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. JAMA network open, 6(6), e2319222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.19222

[3] Middle East respiratory syndrome, Memish, Ziad A et al. The Lancet, Volume 395, Issue 10229, 1063 – 1077

[4] Arabi, Y. M., Asiri, A. Y., Assiri, A. M., Balkhy, H. H., Al Bshabshe, A., Al Jeraisy, M., Mandourah, Y., Azzam, M. H. A., Bin Eshaq, A. M., Al Johani, S., Al Harbi, S., Jokhdar, H. A. A., Deeb, A. M., Memish, Z. A., Jose, J., Ghazal, S., Al Faraj, S., Al Mekhlafi, G. A., Sherbeeni, N. M., Elzein, F. E., … Saudi Critical Care Trials Group (2020). Interferon Beta-1b and Lopinavir-Ritonavir for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. The New England journal of medicine, 383(17), 1645–1656. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2015294

[5] Macrolides in critically ill patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Arabi, Yaseen M. et al., International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 81, 184 - 190

[6] Infection prevention and control during health care for probable or confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-174652

[7] Transmission-based precautions for the prevention and control of infections: aide-memoire. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UHL-IHS-IPC-2022.2

Citable reference: World Health Organization (24 December 2025). Disease Outbreak News; Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus - Global update. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON591