The COVID-19 pandemic and TB in India: impact and response

A. Impact on TB disease burden

Estimates of tuberculosis (TB) disease burden in India for 2000–2019 were published in the World Health Organization (WHO) Global

tuberculosis report 2020 (1). The estimates were based on results from a statewide TB prevalence survey in 2011–2012, time trends in the prevalence of TB infection (measured in surveys), and cause-of-death data from verbal autopsy

studies and a sample vital registration system. Given the disruptions to TB diagnosis and treatment caused by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic (Section 1),

production of estimates of TB disease burden for 2020 specifically required new methods based on dynamic models of TB transmission. The model used for India was informed by near real-time case notification data reported online in Nikshay, the national

TB reporting system (2), which showed a 25% annual shortfall in case notifications in 2020 compared with 2019 (Section 1).

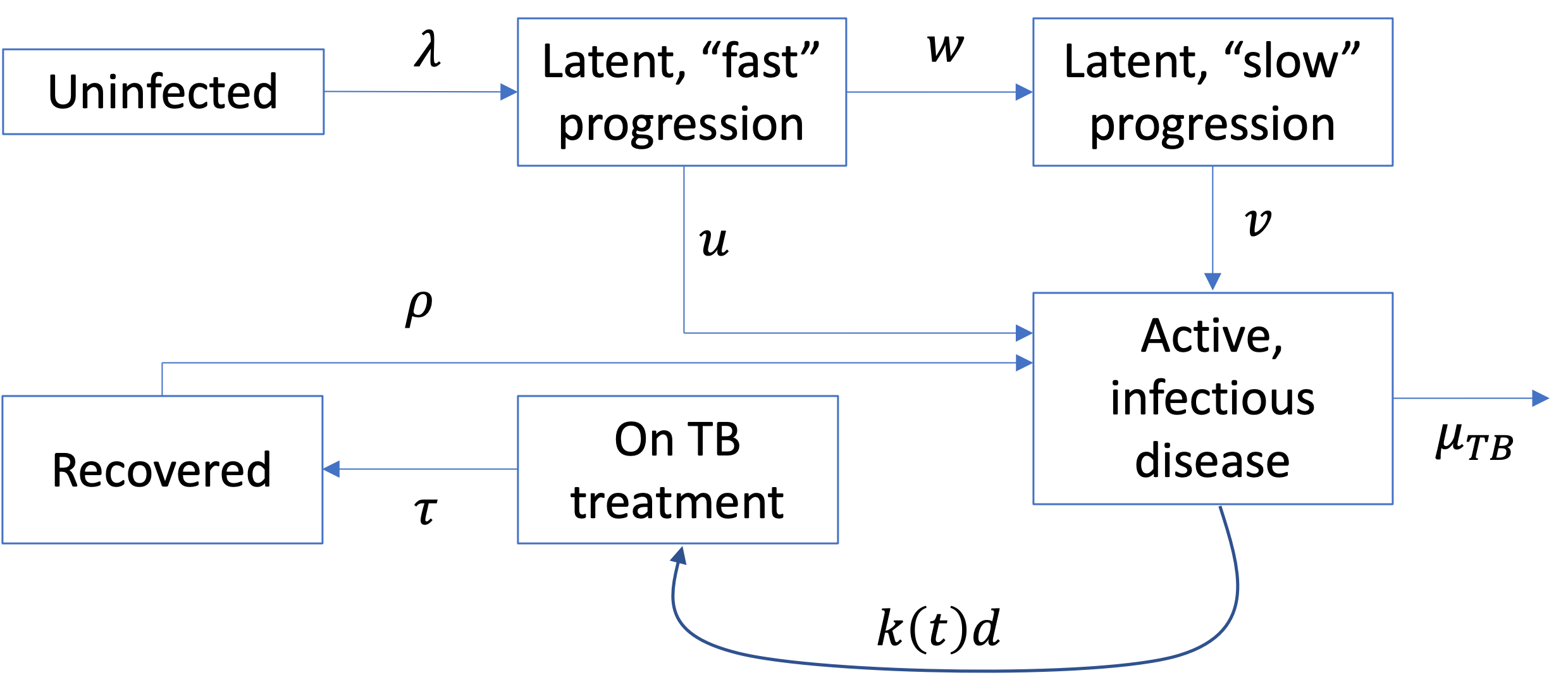

The transmission model is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1 below (details and governing equations are described in the technical annex to the main report). The model captures the COVID-19 response’s indirect effects on TB, focusing on reduced access to care and some level of diagnostic and human resources being diverted to COVID-19 services; overall, these factors have led to delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

As shown in Fig. 1, the effect of routine TB services is to remove individuals with active, infectious TB at a rate d, and to initiate them on TB treatment. The adverse effect of disruptions related to the COVID-19 response is to modify this rate by a time-dependent factor, k(t). Nikshay data for notifications were used to inform the monthly time series for k(t). Other rates shown in Fig. 1 are as follows: λ, time-dependent force of infection; w, per-capita transition rate from “latent, fast” to “latent, slow”; u, per-capita hazard of breakdown to active disease in the first 2 years after infection; v, per-capita rate of reactivation thereafter; μTB, per-capita hazard of TB mortality; τ, per-capita rate of treatment completion; and ρ, per-capita rate of relapse. The values and data sources used for model parameters are shown in Annex 1 below.

The model structure for India accounted for the private and public sectors separately. Other model features that are not shown (for simplicity) in Fig. 1 are reinfection, spontaneous cure and the potential for higher post-treatment relapse following treatment non-completion.

A key assumption was that any reduction in TB case notifications, compared with an extrapolation of pre-2020 trends, was due to delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation rather than shortfalls in reporting. Moreover, it was assumed that the proportion of people with TB who were diagnosed but not reported remained the same in 2020 as in 2019. Delays in diagnosis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may have arisen from factors related to individuals (e.g. people with symptomatic TB being less willing or able to seek care during periods of COVID-19 restrictions) or to health systems (e.g. services having less TB diagnostic or staff capacity than in normal times). The model structure is agnostic to either of these factors; instead, the whole journey of health care seeking is captured in the rate d. This was a deliberate choice in the modelling (usually, additional compartments would be included to reflect the time to seek medical care separately from the time to investigate and diagnose TB).

To capture the implications of reduced notifications for diagnostic delays, the model includes a month-by-month adjustment to the baseline detection rate in 2019, denoted as k(t) in Fig. 1. Monthly values for this adjustment were matched to the monthly time series of Nikshay notification data (Fig. 2). These data provide information separately for the public sector and for private providers reporting to the national TB elimination programme (NTEP). In this way, the model accounts for disruptions in the public and private sectors separately. It was assumed that private sector disruptions evident in Nikshay data could be extrapolated to the private sector in India more broadly.

With its focus on delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation, the model ignores other possible disruptions, including those to treatment continuity among people already on TB treatment. However, previous analysis suggests that such disruptions are likely to have a weaker effect on TB incidence than disruptions to diagnosis and treatment initiation (3).

The model does not include direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as a possible increased risk of mortality in people with both COVID-19 and TB. Preliminary results from the ongoing national TB disease prevalence survey were also not used. For projections post-2020, TB detection and treatment services were assumed to have fully recovered by June 2021.

An important source of uncertainty is the extent to which TB transmission was reduced during periods of national lockdown. Wide uncertainty intervals were adopted, with the strength of reduction assumed to be uniformly distributed between 25% and 75%.

In view of these limitations and others described in Annex 5 of the main report (PDF), the resulting estimates for 2020 and projections up to 2025 should be considered provisional.

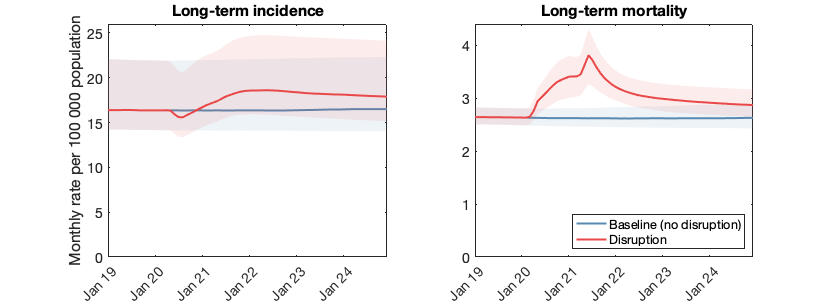

Fig. 3 shows resulting model projections of incidence and mortality. The impact of disruptions related to COVID-19 on case detection is relatively small and delayed, whereas the impact on TB mortality is much bigger and more rapid. The relative decline in TB incidence estimate rates from 2019 to 2020 is 2.8% (2.9% in 2018–2019), indicating only a small slowing down of the pre-COVID-19 decline. In contrast, the TB mortality rate is estimated to have increased by 11% from 2019 to 2020 (compared with a 2.6% decline from 2018 to 2019).

More empirical data on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB in India are needed to support further model refinement and development. Results from the national TB prevalence survey are expected to inform future estimates. It is possible that continued use of masks and physical distancing may have contributed to continued reductions in TB transmission, even after the lifting of formal restrictions. Any emerging evidence to this effect would be incorporated in future estimates.

B. Response by the National TB Elimination Programme

India’s NTEP took various actions to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB services. As a result, the overall impact on TB diagnostic and treatment services was less than the impact on outpatient and inpatient services in general. The number of case notifications of people newly diagnosed with TB fell by 25% in 2020 compared with 2019, while the reduction in the total number of attendances at inpatient and outpatient services was 38%. The main actions taken by the NTEP are highlighted below.

Diagnostic services

Bi-directional screening was introduced to ensure screening for COVID-19 among people diagnosed with TB and screening for TB among people diagnosed with COVID-19. The number of machines for nucleic-acid amplification tests (NAATs) was doubled through the procurement of 159 GeneXpert (CBNAAT) machines and 1512 Truenat machines, which increased diagnostic capacity by an additional 9200 COVID-19 tests and 4600 TB tests per day (4). This helped to ensure that TB diagnostic capacity that had initially been diverted for COVID-19 testing was restored and enhanced; sputum smear microscopy testing for TB was replaced with NAATs for all those with presumptive TB. Laboratory services for TB and COVID-19 testing were also decentralized and integrated to optimize their use. Referral linkages between TB and COVID-19 services were established.

Case finding

Intensified case finding for both TB and COVID-19 were prioritized in all outpatient departments of the public sector, and home-based sample collection services were provided during periods of lockdown. An active TB case-finding campaign was initiated in areas in which relatively few cases of COVID-19 were being detected. Health centres initiated community-based screening for TB using a standardized checklist during house-to-house surveys for population enumeration, and contact tracing was strengthened for the household and workplace contacts of people diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed TB. In addition, migrant camps were mapped as the basis for systematic case finding and patient follow-up and support in these settings.

Considerable efforts were also made to ensure continued engagement with the private sector. A national government directive was issued to state and local administrations after the first lockdown, with the aim of reopening private clinics, hospitals and laboratories. State administrations worked with professional bodies and associations such as the Indian Medical Association, Pediatrics Association of India, Indian Chest Society, and Federation of Obstetric and Gynecological Societies of India to ensure the provision of TB care. Actions included the provision of information about the mandatory nature of case notification and the availability of free anti-TB drugs and diagnostics from the NTEP.

Outreach activities were conducted as part of initiatives such as “Joint efforts for elimination of TB”, and by agencies and nongovernmental organizations providing patient and provider support. A toll-free number was established to provide information to both health professionals and the general public.

Treatment services

People on TB treatment were provided with at least monthly supplies of anti-TB drugs and were given the option of home delivery. Adequate stocks of drugs were ensured, including through the involvement of private chemists and the use of decentralized “drug refill” facilities in urban areas. Digital technologies were used to enable reporting and monitoring of adverse drug reactions without the need to attend a health facility. Airborne infection control measures were implemented in all public health facilities, including in patient registration and waiting areas. Hand-washing facilities and “corners” were also established at government health facilities, alongside information on the mandatory use of masks, physical distancing and cough etiquette.

Patient support

Each district identified a person to handle calls from people with presumptive TB or those already diagnosed with TB, to assist them with services such as sample collection, drug delivery and linkages with a treatment supporter or nearby health care worker. “TB cards” were provided to facilitate assistance for people being investigated or treated for TB. Efforts were made to reduce patient visits to health care facilities and, where possible, services were offered in a single location. A citizen and patient centric application, “TB Aarogya Sathi”, was launched to offer a connection between TB patients and health providers from a distance.

Provider support

Guidelines for standard precautionary measures for health care workers in all health facilities were issued and were accompanied by widespread provision of online training to health staff in the public and private sectors. Plans to progressively relieve NTEP staff from duties related to COVID-19 were implemented.

Direct-benefit transfers

Any pending direct-benefit transfers for people with TB were cleared within 1 month, and the turnaround time for payments was reduced from more than 100 days to less than 30 days. People diagnosed with TB whose bank details were not available were contacted for submission of bank account details in Nikshay, to ensure prompt payments of benefits.

Demand generation

Intensive local communication campaigns about TB and COVID-19 were undertaken. These were aimed at addressing stigma related to COVID-19, improving health care seeking behaviour, and sustaining measures such as social distancing, personal hygiene and mask wearing. Targeted activities were undertaken for key populations including migrants, urban slum dwellers, people living with HIV, miners and farmers.

Rational use of personal protective equipment

General guidance for the rational use and disposal of personal protective equipment (PPE) was issued by India’s Ministry of Health (5).

Monitoring and evaluation

The transition from paper-based recording and reporting of TB data to Nikshay was completed, including laboratory services and commodity procurement. A quarterly national report on the TB situation was provided to all states. Assessment of the burden of TB disease at subnational levels was undertaken and used as the basis for issuing certificates to recognize “achievements for efforts to end TB”. Operational and implementation research was commissioned on priority research topics.

Fig. 1 A schematic illustration of the structure of the TB transmission model used for India

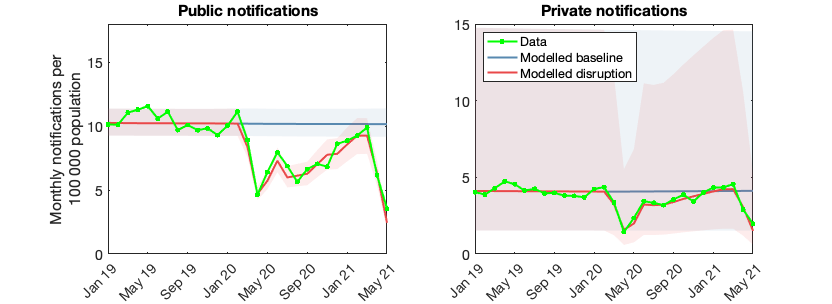

Fig. 2 Model calibration: matching detection rates to case notifications

Data (in green) show notifications from the public and private sectors, on a month-to-month basis. Red lines show model projections, created by choosing a time series for k(t) in Fig. 1 that matches closely with the data. Shaded areas show 95% Bayesian credible intervals.

Fig. 3 Model projections of incidence (left) and mortality (right)

Projections are measured against a baseline scenario (in blue) based on pre-2020 trends. Shaded areas show 95% Bayesian credible intervals.

References

- Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131).

- Nikshay reports [website]. India: Government of India; 2021 (https://reports.nikshay.in/Reports/TBNotification).

- Cilloni L, Fu H, Vesga JF, Dowdy D, Pretorius C, Ahmedov S et al. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tuberculosis epidemic a modelling analysis. EclinicalMedicine, 2020;28:100603.

- India TB Report 2021: National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme – annual report. Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi: Central TB Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2021 (https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3587).

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [website]. India: Government of India; 2021 (https://www.mohfw.gov.in/).

Annex 1: Model parameters and values

Table A1: Model parameter values and data sources used to estimate the TB disease burden in India in 2020 and to produce projections for 2021–2025.

| Calibration targets | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| TB incidence per 100 000 population, 2019 | 193 (132, 266) | (1) |

| TB mortality per 100 000 population, 2019 | 32 (30, 34) | (1) |

| Notifications per 100 000 population, 2019, public | 127 | (2) |

| Notifications per 100 000 population, 2019, private | 50 | (2) |

| Natural history parameters | ||

| LTBI: among “fast” progressors, annual hazard rate of breakdown to active disease | 0.083 (0.062, 0.10) | (3) |

| LTBI: among “slow” progressors, annual hazard rate of reactivation to active disease | 6x10–4 (4.5x10–4, 7.5x10–4) | (3) |

| Number of infections per untreated TB case per year | 12.2 (9.2–16) | Calibrated to data for incidence |

| Annual mortality hazard in the absence of treatment | 0.67 (0.50, 0.84) | (4), parameters determined so that untreated TB case has an average duration of 3 years with CFR of 50% |

| Per-capita rate of self-cure in the absence of treatment | 0.67 (0.50, 0.84) | (4), parameters determined so that untreated TB case has an average duration of 3 years with CFR of 50% |

| TB care parameters | ||

| Average delay before initiation of TB treatment (pre-COVID-19, including patient delay) | 7.9 mo (5.1–15) | Calibrated to data for incidence and notifications |

| Proportion of TB patients being managed by the public (vs private) sector | 61% (52–78%) | Calibrated to match data for notifications by public sector |

| Completion rates for first-line TB treatment, public | 84% | (2) |

| Completion rates for first-line TB treatment, private (unengaged) | 79% | (2) |

| Post-TB parameters | ||

| Protection from reinfection from past TB | 80% (60–90%) | (5) |

| Post-cure hazard of relapse, following successful treatment completion | 0.032 (0.02–0.04) | (6) |

| Post-cure hazard of relapse, following self-cure or treatment interruption | 0.14 (0.1–0.2) | (7), assuming same hazard of relapse for self-cure as for those interrupting treatment |

References (Table A1)

- Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131).

- India TB report 2020. Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi: Central TB Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2020 (https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3538).

- Menzies NA, Wolf E, Connors D, Bellerose M, Sbarra AN, Cohen T et al. Progression from latent infection to active disease in dynamic tuberculosis transmission models: a systematic review of the validity of modelling assumptions. Lancet Infect Dis.

2018;18:e228–38.

- Tiemersma EW, van der Werf MJ, Borgdorff MW, Williams BG, Nagelkerke NJD. Natural history of tuberculosis: duration and fatality of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV negative patients: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17601.

- Andrews JR, Noubary F, Walensky RP, Cerda R, Losina E, Horsburgh CR. Risk of progression to active tuberculosis following reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:784–91.

- Subbaraman R, Nathavitharana RR, Satyanarayana S, Pai M, Thomas BE, Chadha VK et al. The tuberculosis cascade of care in India’s public sector: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002149.

- Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Martin I, Royce S, Pai M et al. Effect of duration and intermittency of rifampin on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000146.