Molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance

Summary texts and tables for P. falciparum

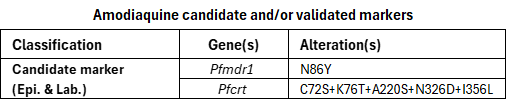

Amodiaquine, a 4-aminoquinoline, is used in combination with artesunate as artesunate–amodiaquine (ASAQ), one of the artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Amodiaquine is also used for chemoprevention, particularly as part of seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in combination with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP).

Reduced P. falciparum susceptibility to amodiaquine has mainly been associated with mutations in the Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 genes. These associations are influenced by parasite genetic background, and associations observed in vitro are generally weaker than those observed for chloroquine. The limited clinical association between these mutations and treatment outcomes likely reflects the modest reduction in amodiaquine susceptibility conferred by these mutations, as well as the probable need for additional genetic changes to produce a clinically significant effect. Consequently, as shown in the table below, the review identified only 2 candidate markers based on laboratory and epidemiological evidence. Studies have also reported selection of the PfMDR1 D1246Y mutation following treatment regimens containing amodiaquine. However, in vitro data indicate that the association between D1246Y and reduced amodiaquine susceptibility is minimal, and this mutation has not been included in the compendium as a marker (PMID: 27596849, 25199781).

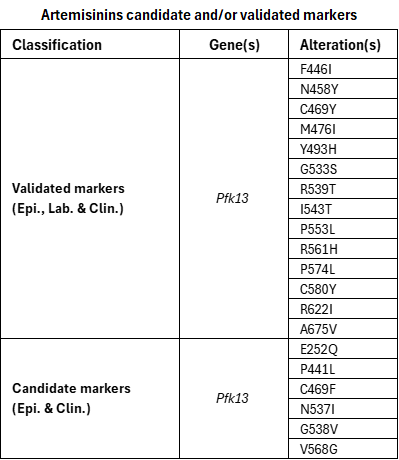

Artemisinin derivatives, such as artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin, are sesquiterpene lactones present in all artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria and are also used parenterally in the treatment of severe malaria.

Artemisinin partial resistance in P. falciparum is characterized in patients by delayed parasite clearance following treatment with an artemisinin derivative. In vitro, this phenotype is characterized by increased survival of early ring-stage parasites in the ring-stage survival assay (RSA), rather than by changes in IC50 values. Only early ring stages show reduced susceptibility, while later stages remain fully sensitive, giving rise to the term “partial resistance”. Artemisinin partial resistance is associated with specific single point mutations in the PfKelch13 (k13) gene. ACTs have been shown to retain high efficacy in areas with a high prevalence of markers of artemisinin partial resistance, provided that parasites remain sensitive to the ACT partner drugs.

Since 2014, WHO has maintained a list of single point mutations validated as molecular markers for artemisinin partial resistance. This review re-examined all markers using available laboratory, clinical, and epidemiological data to ensure consistent classification according to the supporting evidence. All previously validated PfKelch13 mutations retained their classification, and an additional mutation (G533S) was added to the validated marker group. One additional candidate marker (E252Q) was included. Some previously listed candidate markers were reviewed and reclassified as potential or not included due to their rare occurrence or insufficient evidence to meet the defined thresholds. The mutation A578S has been identified at high prevalence in several studies in Asia and Africa but has not been associated with clinical or in vitro resistance to artemisinin. Mutations in Pfcoronin have been reported as potential markers of artemisinin partial resistance based only on laboratory data.

the magnitude of the effect conferred by a marker can vary depending on the parasite’s genetic background, and this should be considered when interpreting results. Classifications will continue to be refined as further evidence becomes available from different epidemiological settings.

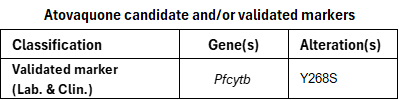

Atovaquone, a hydroxynaphthoquinone, is mainly used in combination with proguanil as atovaquone–proguanil for malaria prophylaxis in travellers. This combination was developed to overcome clinical resistance to earlier antimalarials, based on evidence that proguanil synergistically enhances the activity of the cytochrome bc1 inhibitor atovaquone.

In areas where atovaquone–proguanil has been used for treatment, P. falciparum resistance to atovaquone was reported soon after its introduction. Clinically, resistance has been reported as late treatment failure following atovaquone-proguanil administration and, in vitro, as increased IC50 values. The combination is rarely used for treatment in endemic countries, which limits the amount of clinical data, although some findings from travellers have been included in this review.

Resistance has been associated with point mutations in the Pfcytb gene, which encodes the cytochrome b subunit of the mitochondrial bc1 complex. Resistance to atovaquone is currently associated with one validated marker, PfCYTB Y268S, which has been detected in patients after treatment. Other substitutions at this codon, including Y268C, for which only clinical data are available, have also been reported. Additional mutations in the Pfcytb gene are listed as potential markers based on laboratory evidence, as shown in the compendium.

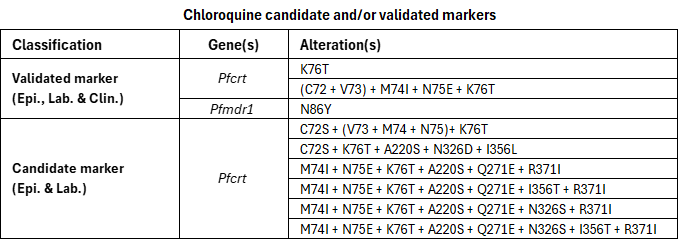

Chloroquine, a 4-aminoquinoline, was widely used for decades for the treatment and prevention of malaria. This led to the independent emergence of chloroquine resistance in South-East Asia and South America, followed by its spread from Asia to Africa. Resistance has since spread to nearly all regions where P. falciparum malaria occurs, except parts of Mesoamerica. Today, chloroquine is mainly used in the treatment of non-P. falciparum malaria.

P. falciparum resistance to chloroquine is primarily linked to mutations in the Pfcrt gene and modulated by alterations in the Pfmdr1 gene. The PfCRT K76T mutation has been shown to be necessary but not sufficient for chloroquine resistance. Other mutations in the Pfcrt gene are rarely found alone and appear to modulate resistance in combination with K76T; therefore they are not listed individually but reflected only within the PfCRT haplotypes included in the compendium. Most studies have focused on codons 72–76, which define distinct PfCRT haplotypes found in different regions, including CVIET (C72+V73+M74I+E75+K76T), the haplotype that originated in South-East Asia and spread to Africa, and SVMNT (C72S+V73+M74+N75+K76T), which is characteristic of South America and parts of Oceania. Clinical evidence linking the SVMNT haplotype to treatment failure remains limited, so it is listed in the compendium as a candidate rather than a validated marker.

In the compendium, several extended haplotypes containing either CVIET or SVMNT together with additional mutations are listed as candidate markers. This reflects the limited clinical evidence available for these extended haplotypes, as most studies have focused on the codons 72–76 rather than the complete Pfcrt sequence. Although the PfMDR1 N86Y mutation is listed as a validated marker of chloroquine resistance, it is considered to play a modulatory role rather than an independent one. It contributes to a modest increase in chloroquine resistance in parasites that already possess PfCRT variants associated with resistance.

Cycloguanil, a dihydrotriazine derivative and dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor (antifolate), is the active metabolite of proguanil. In the compendium, the focus is on cycloguanil rather than proguanil, because proguanil has a short in vivo half-life and limited intrinsic antimalarial activity. Proguanil was introduced for malaria treatment in the 1940s, but resistance emerged soon after its introduction. The atovaquone–proguanil combination was subsequently developed to overcome clinical resistance. Today, this combination is used mainly for malaria treatment outside endemic areas and prophylaxis in travellers.

Cycloguanil targets dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and laboratory studies have shown that resistance is associated with mutations in the Pfdhfr gene. However, because the drug is not widely used, clinical data on cycloguanil resistance remain limited, and the available evidence is derived only from laboratory studies. Thus, only potential markers are included in the compendium.

Lumefantrine, an aryl amino alcohol, is used in combination with artemether as artemether–lumefantrine (AL), one of the ACTs recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. AL is the most widely used ACT worldwide.

Recent in vitro studies using field-collected isolates have shown modest decreases in lumefantrine susceptibility. However, the clinical relevance of these findings remains uncertain and does not constitute evidence of resistance (PMID: 40783405).

Therapeutic efficacy studies (TES) have not demonstrated consistent associations between the genetic alterations evaluated and clinical outcomes. Interpretation of TES data remains challenging because of methodological limitations, such as the lack of directly observed administration of all AL doses and the difficulty of distinguishing reinfection from recrudescence.

The review did not identify any validated or candidate molecular markers associated with lumefantrine resistance. One potential marker, Pfmdr1 gene amplification, has been identified based on in vitro evidence. This marker has also been associated with decreased susceptibility to other antimalarial drugs.

Parasites carrying wild-type PfCRT (CVMNK at codons 72–76) or PfMDR1 N86 and 184F have been reported to exhibit reduced in vitro susceptibility to lumefantrine. However, the degree of reduced susceptibility appears modest and varies across parasite populations. In some locations, these genotypes are found at high prevalence where lumefantrine is used and amodiaquine is not, but based on the available evidence, they have not been included as molecular markers of resistance.

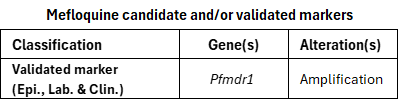

Mefloquine, an aryl amino alcohol, is used in combination with artesunate as artesunate–mefloquine (ASMQ), one of the artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. ASMQ for treatment has been used primarily in Asia and South America. Mefloquine has also been used for prophylaxis in travellers.

Mefloquine resistance has been associated with amplification of the Pfmdr1 gene. This is considered a validated molecular marker, supported by laboratory, clinical, and epidemiological evidence from South-East Asia.

Some PfCRT haplotypes and certain PfMDR1 mutations, each associated with chloroquine resistance, have been reported to modestly increase mefloquine susceptibility in vitro, although no consistent association with clinical outcomes has been demonstrated.

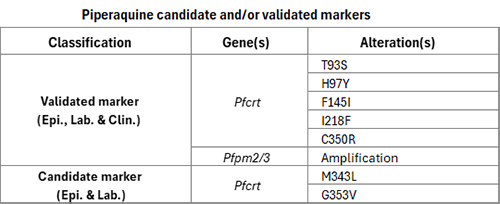

Piperaquine, a bisquinoline, is used in combination with dihydroartemisinin, as dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (DHA–PPQ), one of the artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Clinically, resistance has been reported as late treatment failure following DHA–PPQ administration and, in vitro, as increased parasite survival in the piperaquine survival assay (PSA).

Piperaquine resistance has been associated with mutations in the Pfcrt gene and amplification of the Pfplasmepsin 2-3 (Pfpm2/3) genes. These have been reported in South-East Asia and, more recently, in parts of South America. The observed Pfcrt mutations differ between regions: several distinct amino acid substitutions have been identified in South-East Asia, while a single variant, C350R, has been reported in South America. The phenotypic effects of Pfcrt mutations have been shown to vary depending on the other mutations observed in the PfCRT haplotype. In studies in which the effects of Pfcrt mutations were examined in different PfCRT haplotypes, their impact on in vitro piperaquine susceptibility differed according to the genetic context of the parasite strain in which Pfcrt mutations were studied.

Studies with gene-edited P. falciparum parasites cultured in vitro show that certain Pfcrt mutations confer moderate to high levels of resistance even in the absence of Pfpm2/3 amplifications. Amplification of the tandem Pfpm2/3 genes alone is associated with a modest reduction in in vitro piperaquine susceptibility, but its co-occurrence with specific piperaquine resistance-conferring Pfcrt mutations leads to higher levels of resistance.

Pyronaridine, a benzonaphthyridine derivative, is used in combination with artesunate as artesunate–pyronaridine (ASPY), one of the ACTs recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. ASPY is the most recently recommended ACT and is not widely used to date.

The review examined genetic alterations reported in the literature as potentially associated with pyronaridine resistance but found none with sufficient evidence to warrant inclusion in the compendium. No resistance to pyronaridine has been demonstrated yet. Therefore, no resistance marker for this antimalarial has been incorporated into the compendium.

Quinine, a quinoline methanol alkaloid, has been used for centuries as one of the earliest antimalarial medicines. It is no longer recommended for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Its current use is primarily restricted to the management of severe malaria in settings where artesunate or artemether is unavailable. Resistance to quinine was first reported in 1910 (PMID: 24331212). Because quinine is now rarely used, data on confirmed clinical failures are limited.

Studies have indicated that decreased susceptibility to quinine may be associated with alterations in Pfcrt and, to a lesser degree, Pfmdr1, a pattern also observed with other quinoline antimalarials, such as chloroquine, although the underlying relationship appears more complex. The review found no validated or candidate molecular markers of quinine resistance; only potential markers were identified based on laboratory evidence.

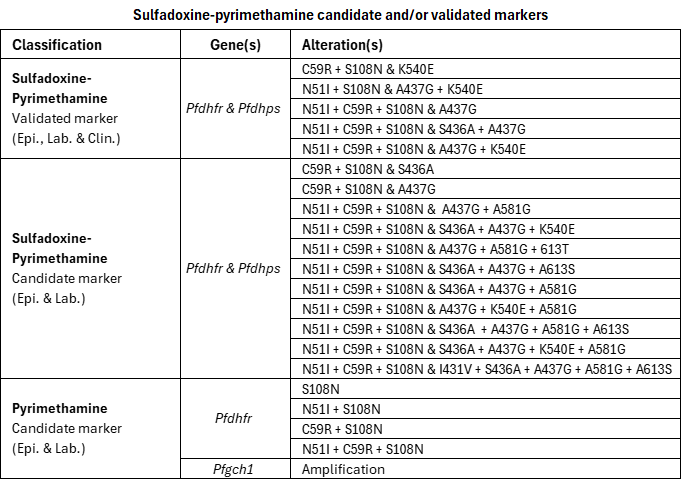

Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) is a fixed-dose combination of sulfadoxine, a sulfonamide, and pyrimethamine, a diaminopyrimidine derivative that acts as a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor (antifolate). It is also used in combination with artesunate as artesunate–sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (ASSP), one of the artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) recommended by WHO for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. However, due to SP resistance, ASSP is not widely used. Today, SP is primarily used for chemoprevention, either alone, for example for intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) and perennial malaria chemoprevention (PMC), or in combination with amodiaquine for seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC).

Resistance arises through the stepwise accumulation of mutations in 2 parasite genes: Pfdhfr (conferring resistance to pyrimethamine) and Pfdhps (conferring resistance to sulfadoxine). Some mutations or haplotypes occur only in combination with other alterations and are rarely, if ever, found in isolation. Therefore, they were not included as individual markers.

Because direct in vitro data for combined Pfdhfr–Pfdhps haplotypes are limited, laboratory evidence from within-gene haplotypes or individual mutations in Pfdhfr or Pfdhps was, where appropriate, applied to update the evidence score of corresponding combined haplotypes that include the same experimentally characterized components.

Reduced clinical efficacy is generally observed when mutations accumulate in both genes. SP is currently most often used for chemoprevention; however, chemoprevention studies were excluded from this review. Clinical evidence relied instead on studies assessing treatment failure. Evidence to date shows that markers predicting loss of treatment efficacy do not necessarily predict loss of protective benefit.

Some combined Pfdhfr–Pfdhps haplotypes including those with 6 or more mutations, remain uncommon. Consequently, clinical data linking these haplotypes to treatment outcomes remain insufficient, and they are classified as candidate markers only.

Copy-number variation in Pfgch1 has also been identified as a candidate marker for pyrimethamine resistance and is observed more frequently in cases where parasites harbour the Pfdhfr I164L mutation that affords high-level pyrimethamine resistance.