2.2 Diagnostic testing

An essential step in the pathway of tuberculosis (TB) care is rapid and accurate diagnostic testing. Since 2011, rapid molecular tests that are highly specific and sensitive have transformed the TB diagnostic landscape, which previously relied upon more traditional microscopy and culture methods.

People diagnosed with TB using rapid molecular tests recommended by WHO (1), lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan (LF-LAM) assays, sputum smear microscopy or culture are defined as “bacteriologically confirmed” cases of TB (2). The microbiological detection of TB is critical because it allows people to be correctly diagnosed and started on the most effective treatment regimen as early as possible. People diagnosed with TB in the absence of bacteriological confirmation are referred to as “clinically diagnosed” or “bacteriologically unconfirmed” cases of TB (2,3).

Bacteriological confirmation of TB is necessary to test for resistance to anti-TB drugs. This can be done using rapid molecular tests, phenotypic susceptibility testing or genetic sequencing.

Fig. 2.2.1 provides an overview of global numbers in 2024 related to diagnostic testing for TB as well as resistance to two first-line drugs: rifampicin and isoniazid.

Fig. 2.2.1 Global overview of numbersa related to TB diagnosis as well as testing for resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid, 2024

a Numbers in the first 4 bars refer to people with a new episode of TB (new or recurrent cases). Numbers in the last two bars are for people with a new episode of TB as well as for people with re-registered for TB.

Rapid diagnostic testing

At the second United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on TB in 2023, Member States adopted a new target that, by 2027, 100% of people diagnosed with TB should be initially tested with a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test (WRD) (4).

Globally, there is a big gap between the number of people newly diagnosed with TB and the number of these people who were initially tested with a WRD (Fig. 2.2.1).

A WRD was used as the initial diagnostic test for 54% (4.5 million) of the 8.3 million people newly diagnosed with TB in 2024, an increase from 48% (out of a total of 8.2 million) in 2023 and up from 47% (out of a total of 7.5 million) in 2022 (Fig. 2.2.2). Among WHO regions, the best level of coverage was achieved in the European Region (77%) and the Western Pacific Region (70%); the lowest coverage was in the South-East Asia Region (41%).

Fig. 2.2.2 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with TB who were initially tested with a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test (WRD), globally and for WHO regions, 2015–2024a

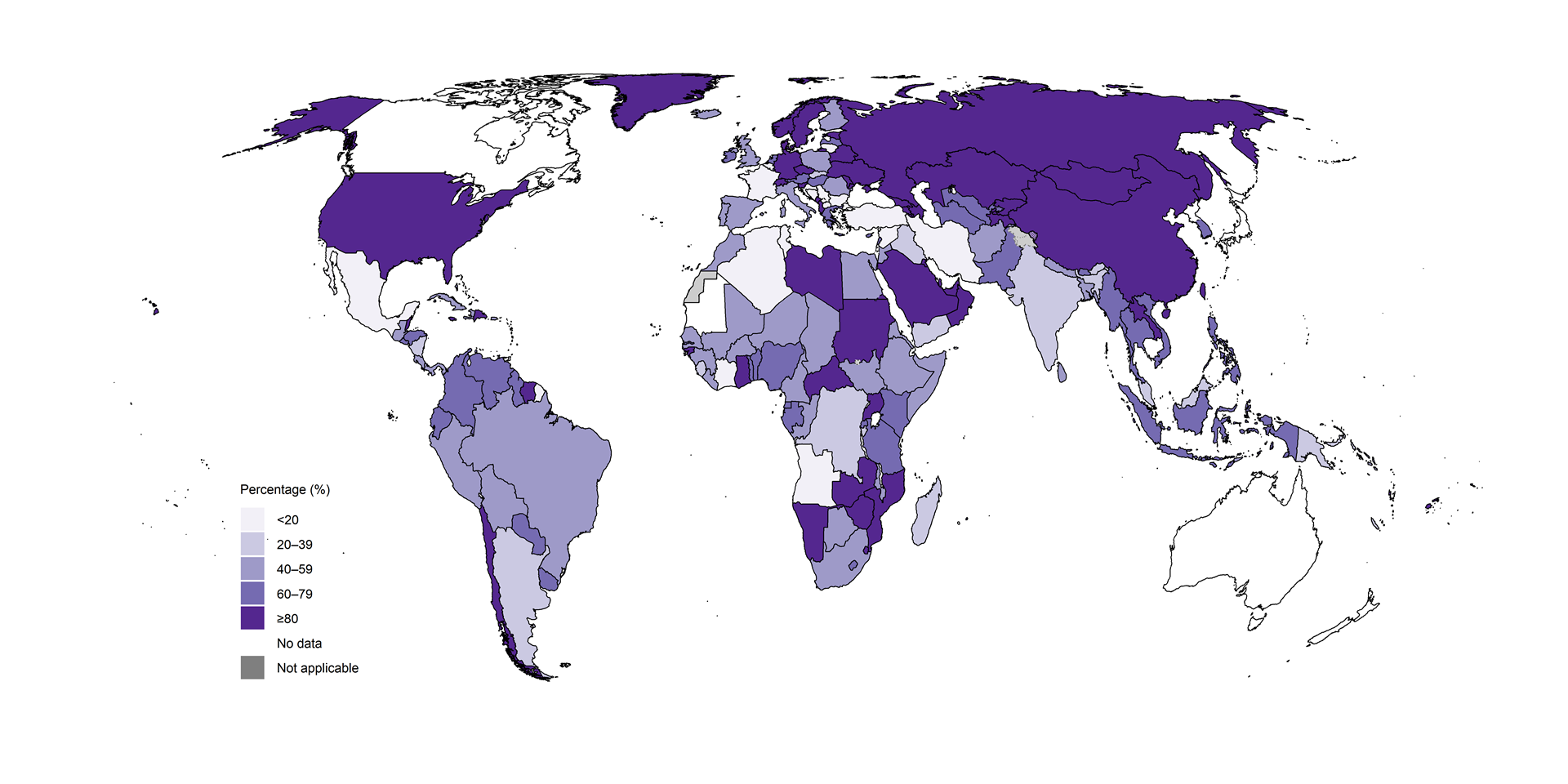

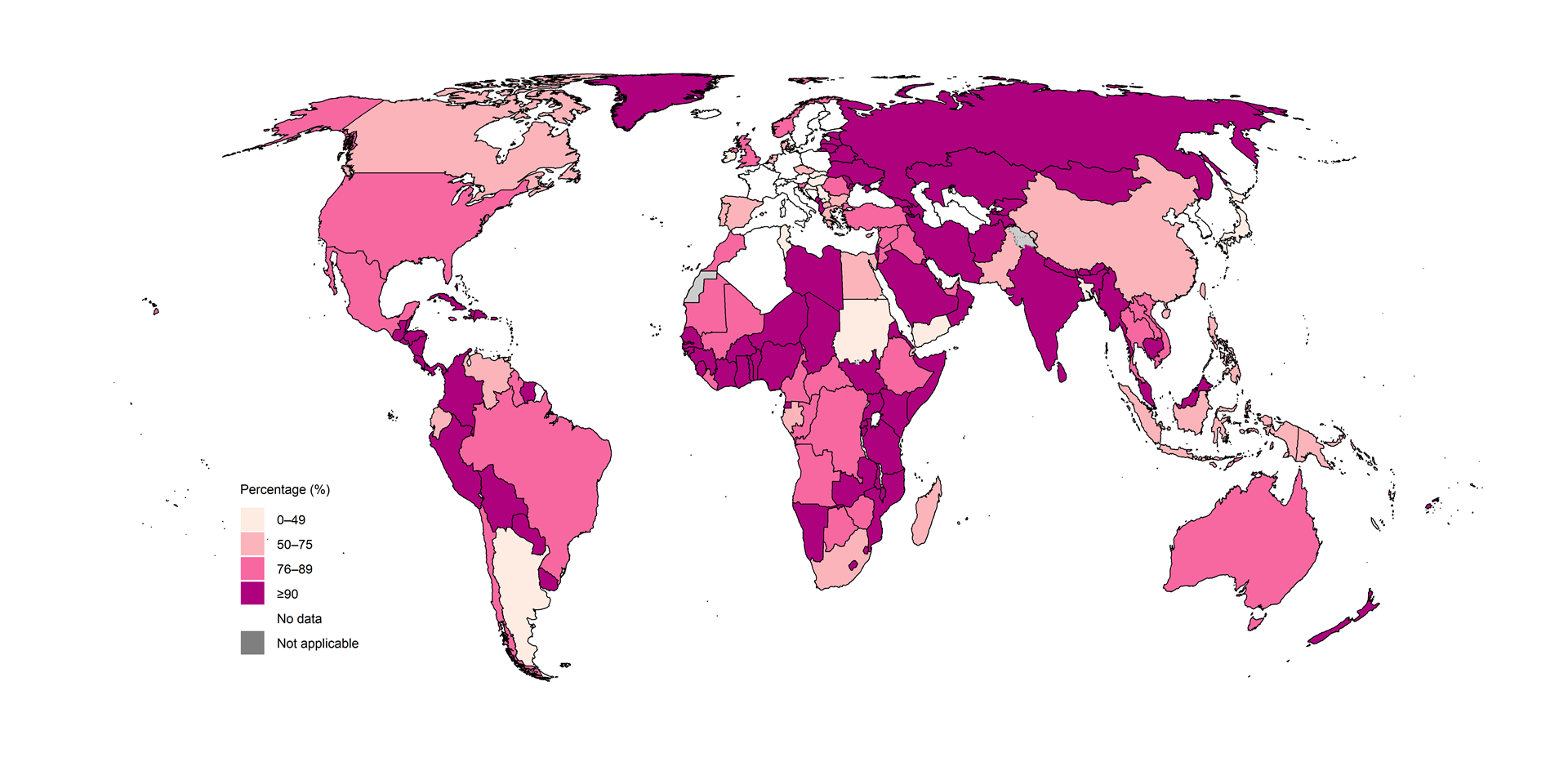

Use of WRDs varied substantially among countries in 2024

(Fig. 2.2.3).

Fig. 2.2.3 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with TB who were initially tested with a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test (WRD),a 2024

Among the 30 high TB burden countries, those with high

proportions (≥80%) of people newly diagnosed with TB who were initially

tested with a WRD in 2024 included the Central African Republic, China,

Mongolia, Mozambique, Namibia, Uganda and Zambia

(Fig. 2.2.4).

Among the 49 countries in one of the three global lists of high burden countries (for TB, HIV-associated TB and MDR/RR-TB) being used by WHO in the period 2021–2025 (Annex 3 of the core report document), 37 reported that a WRD had been used as the initial test for more than half of their notified TB cases in 2024, up from 31 in 2023.

Fig. 2.2.4 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with TB who were initially tested with a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test (WRD), 30 high TB burden countries, 2015–2024

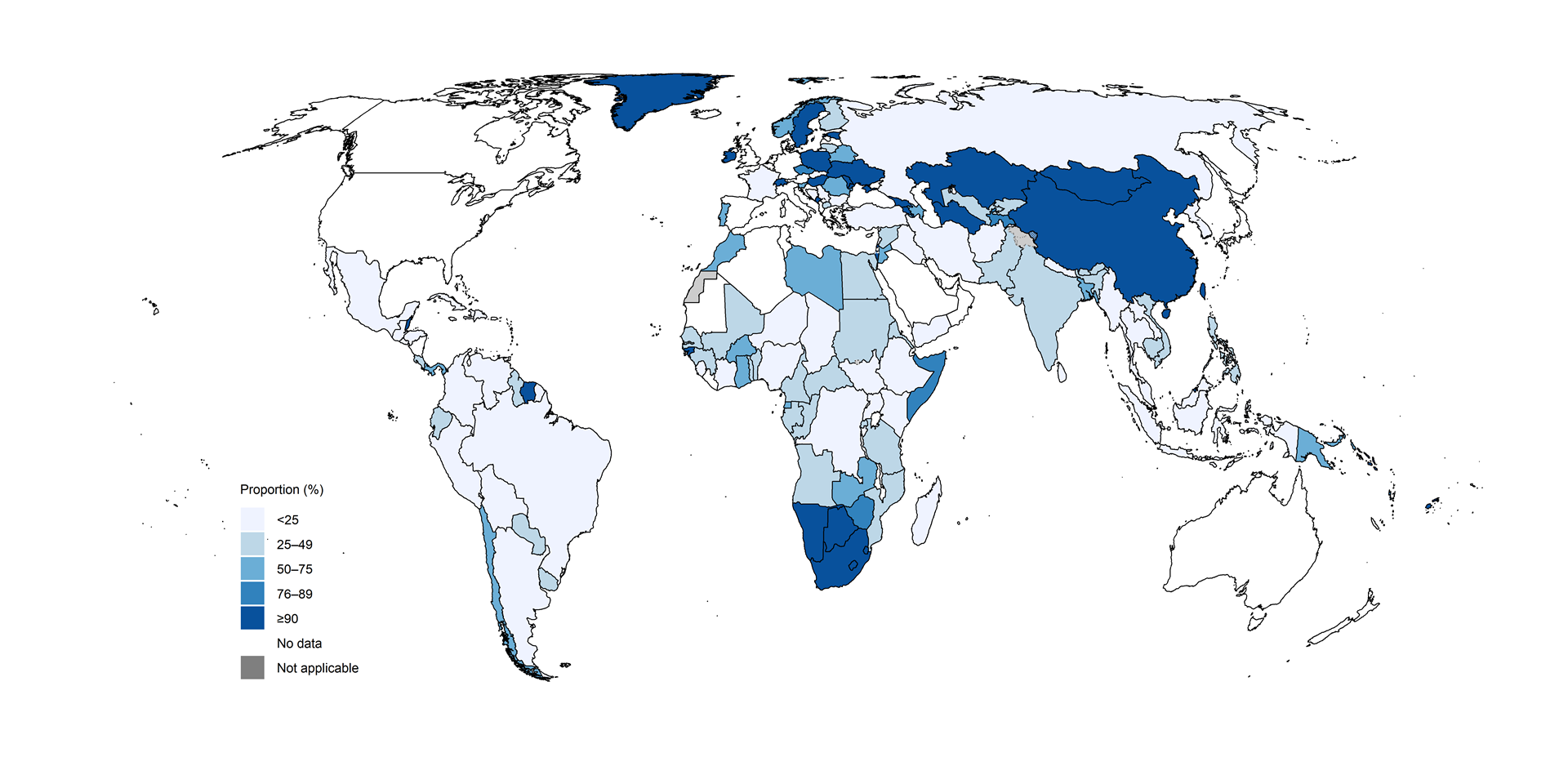

A major influence on the coverage of rapid testing is the

proportion of TB diagnostic sites with access to WRDs. In 2024, this

varied considerably by country (Fig. 2.2.5). Only eight of the 30 high TB burden

countries reported that more than 50% of their TB diagnostic sites had

access to WRDs: Bangladesh, China, Lesotho, Mongolia, Namibia, Papua New

Guinea, South Africa and Zambia. This list was unchanged compared with

2023. Expanding access to TB diagnosis using rapid tests should be a top

priority for all countries.

Fig. 2.2.5 Proportion of diagnostic sites for TB with access to WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic tests (WRDs), by country, 2024

Bacteriological confirmation

A global total of 8.3 million people were newly diagnosed with TB and notified as a TB case in 2024; of these, 6.9 million (84%) had pulmonary TB (Fig. 2.2.1, Table 2.1.1 of Section 2.1). Worldwide, the percentage of people diagnosed with pulmonary TB based on bacteriological confirmation improved between 2018 and 2021, from 55% to 63%; however, it remained relatively stable, at 62%–64%, in 2022–2024 (Fig. 2.2.6). Among the six WHO regions, there were steady improvements between 2020 and 2024 in the African Region (from 65% to 70%) and the Region of the Americas (from 77% to 81%); in other regions, levels of bacteriological confirmation were either stable or fell slightly. Efforts to reach the level already achieved in the Region of the Americas are required in other regions.

Fig. 2.2.6 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with pulmonary TB who were bacteriologically confirmed, globally and for WHO regions,a 2010–2024

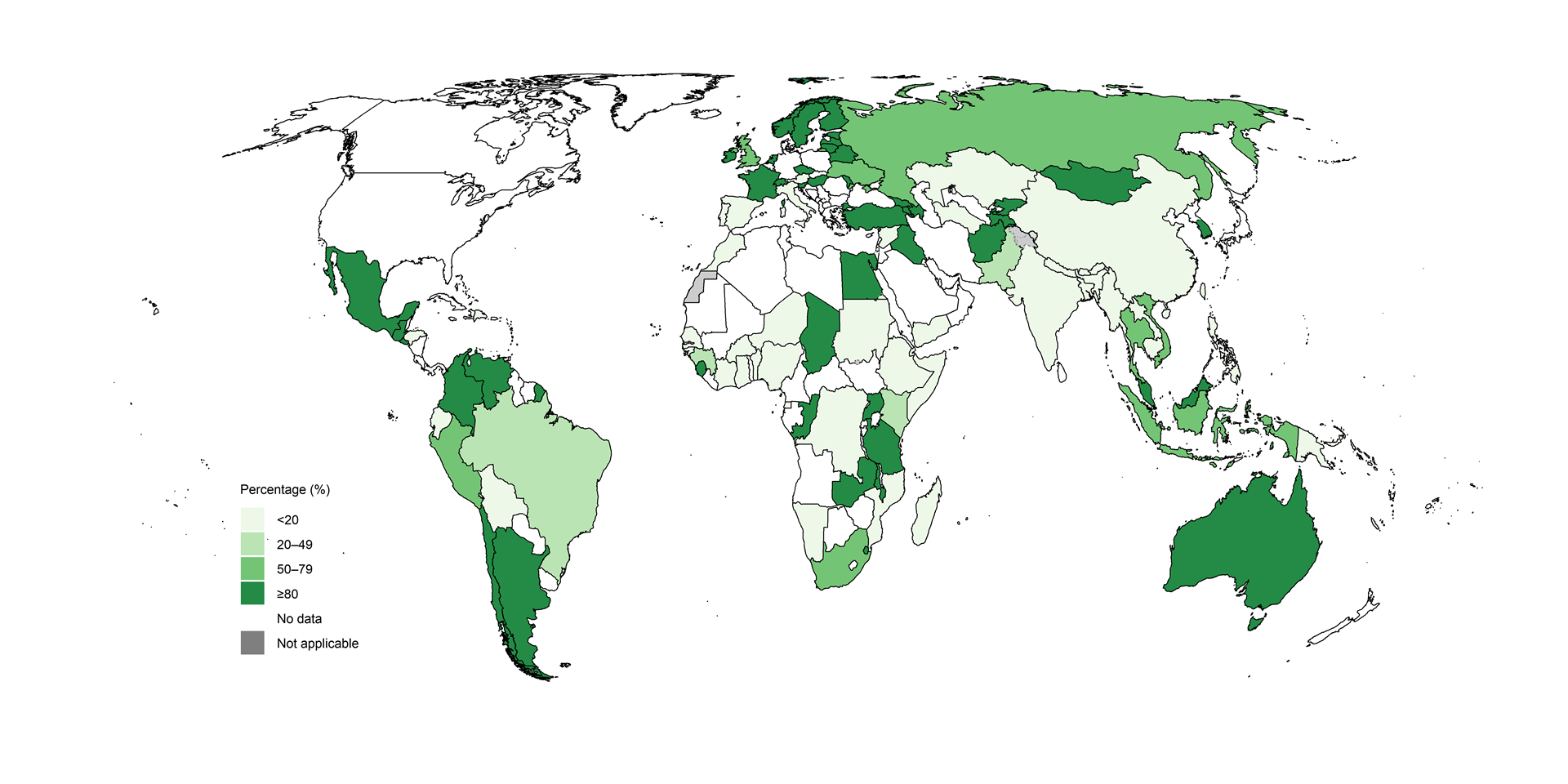

In 2024, there was considerable country variation in the

proportion of people newly diagnosed with pulmonary TB who were

bacteriologically confirmed (Fig. 2.2.7).

Fig. 2.2.7 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with pulmonary TB who were bacteriologically confirmed, by country,a 2024

In the 30 high TB burden countries

(Fig. 2.2.8),

variation in the proportion of people diagnosed with pulmonary TB who

were bacteriologically confirmed likely reflects differences in

diagnostic and reporting practices, including access to rapid diagnostic

tests. The countries with relatively high levels of bacteriological

confirmation in 2024 (75% or above) were Bangladesh, Liberia, Mongolia,

Namibia, Nigeria and Viet Nam.

There is clear scope for improvement in most other high TB burden countries. This is particularly needed in Angola, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Lesotho, Mozambique, Myanmar, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, where levels of bacteriological confirmation remained around or below 50% in 2024. Such levels of bacteriological confirmation show overdependence on clinical diagnosis of TB and potentially over-diagnosis. When the proportion of people diagnosed with pulmonary TB based on bacteriological confirmation falls to around or below 50%, a review of the diagnostic tests in use and the validity of clinical diagnoses is warranted (e.g. via a clinical audit).

Among other 30 high TB burden countries, four have made considerable progress in recent years: China, the Congo, Ethiopia and Thailand.

Fig. 2.2.8 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with pulmonary TB who were bacteriologically confirmed, 30 high TB burden countries,a 2010–2024

Resistance to rifampicin

Bacteriological confirmation of TB is required to test for drug resistance. To ensure that people are enrolled on the right TB treatment regimen, all those diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed TB should be tested for resistance to rifampicin (the most effective first-line anti-TB drug) (5).

Globally in 2024, 83% of people with bacteriologically confirmed TB were tested for rifampicin-resistance TB (RR-TB), an improvement from 79% in 2023 and major progress compared with 69% in 2021 (Fig. 2.2.9). There has been substantial progress in recent years in all six WHO regions. In 2024, the highest coverage of testing (≥80%) was in the European, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions.

Fig. 2.2.9 Percentage of people diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed TB who were tested for rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TBa), globally and for WHO regions, 2010–2024

In 2024, there was considerable variation among countries in the coverage of testing for RR-TB (Fig. 2.2.10). Of the 30 countries (see Annex 3 of the core report document) that WHO has defined as high burden for multidrug-resistant/RR-TB (MDR/RR-TB; MDR-TB is defined as resistance to both rifampicin and isoniazid), 24 reached a coverage of at least 80% in 2024: Angola, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Somalia, South Africa, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, Zambia and Zimbabwe. There were three high MDR/RR-TB burden countries that did not reach a coverage level of 50%: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (1.6%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (35%) and Mozambique (31%).

Fig. 2.2.10 Percentage of people diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed TB who were tested for rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TBa), by country, 2024

Among people tested for RR-TB, a total of 147 592 cases of

MDR/RR-TB and 25 140 cases of pre-extensively drug-resistant TB

(pre-XDR-TB) or XDR-TB were notified in 2024 (Table

2.1.1), for a combined total of 172 732. This was a decrease

(-8.9%) from a combined total of 189 631 in 2023 (Section

2.1).

Resistance to fluoroquinolones and bedaquiline

Fluoroquinolones (a class of second-line anti-TB drug), bedaquiline and linezolid are recommended by WHO as part of treatment regimens for people with drug-resistant TB (5).

All those with RR-TB should be tested for pre-extensively drug-resistant TB (pre-XDR-TB), defined as resistance to rifampicin as well as any fluoroquinolone (6). Those with pre-XDR-TB should be tested for extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), defined as resistance to rifampicin, any fluoroquinolone and at least one of either bedaquiline or linezolid.

There are major gaps in the global cascade of diagnostic testing for pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB (Fig. 2.2.11).

Fig. 2.2.11 Global cascade of diagnostic testinga for rifampicin-resistant TB, pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB, 2024

Globally in 2024, the percentage of people diagnosed with RR-TB who were tested for resistance to fluoroquinolones was 58%, a small improvement from 55% in 2023 and 50% in 2022 (Fig. 2.2.12). Among WHO regions in 2024, coverage was highest in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (90%) and lowest in the Western Pacific Region (41%).

Fig. 2.2.12 Percentage of people diagnosed with rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) who were tested for resistance to fluoroquinolones,a globally and for WHO regions, 2015–2024

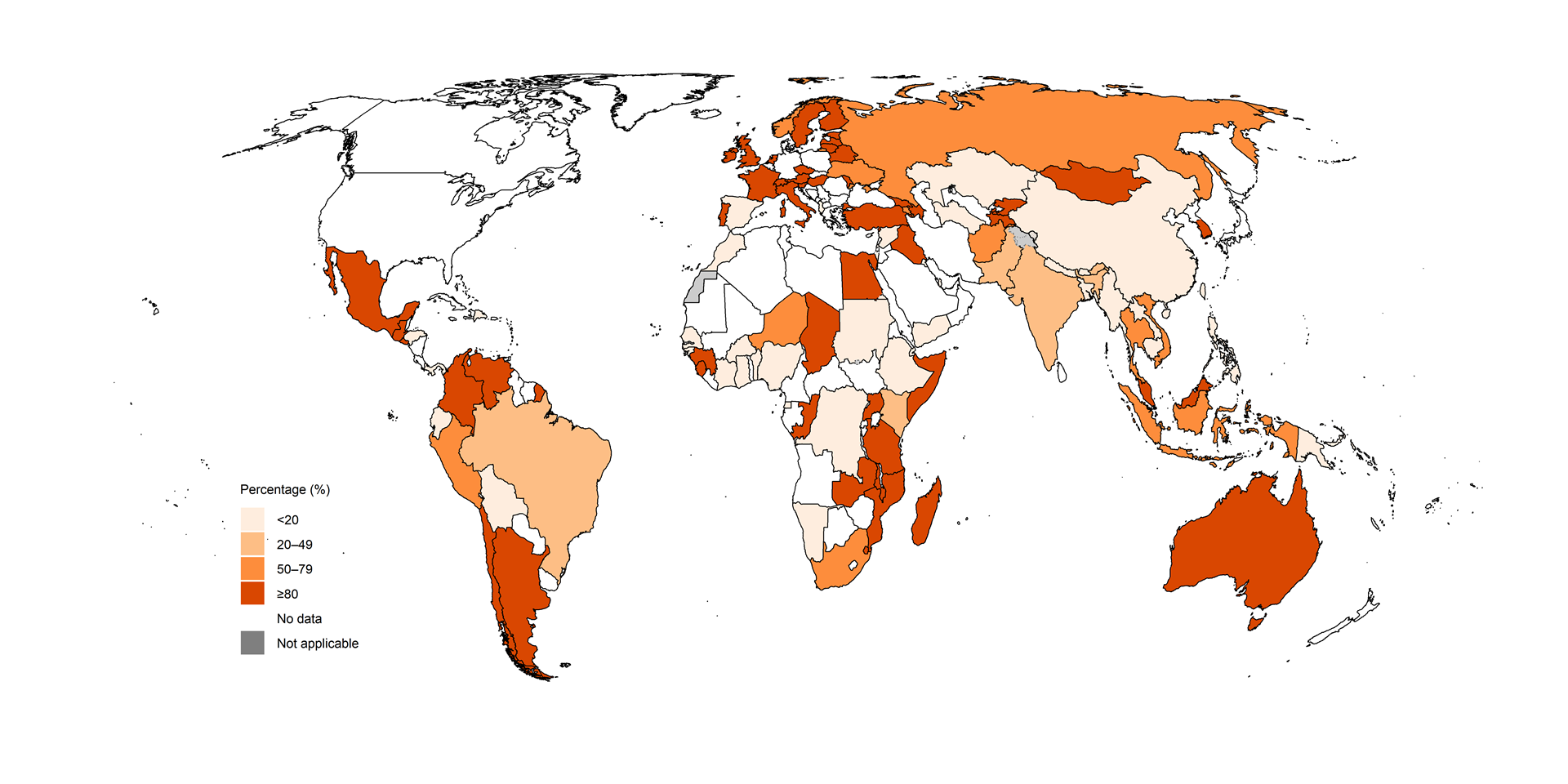

There is considerable country variation in the proportion of

people diagnosed with RR-TB who were tested for resistance to

fluoroquinolones (Fig.

2.2.13).

Fig. 2.2.13 Percentage of people diagnosed with rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) who were tested for resistance to fluoroquinolones, by country, 2024

In 2024, the number and percentage of people with pre-XDR-TB who were tested for resistance to bedaquiline remained low (Fig. 2.2.11,Fig. 2.2.14).

Fig. 2.2.14 Percentage of people diagnosed with pre-XDR-TBa who were tested for resistance to bedaquiline, by country, 2024

The coverage of testing for resistance to bedaquiline for people with RR-TB was lower still (Fig. 2.2.15).

However, a total of 23 countries reached a coverage of at least 80% in 2024: Armenia, Belarus, Chile, Czechia, Egypt, Eswatini, Finland, France, Georgia, Guatemala, Iraq, Ireland, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, the Marshall Islands, the Netherlands, Norway, the Republic of Moldova, Slovenia, Sweden, Ukraine and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Fig. 2.2.15 Percentage of people diagnosed with rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) who were tested for resistance to bedaquiline, by country, 2024

In 2024, the percentage of people with pre-XDR-TB who were

tested for resistance to linezolid varied substantially

(Fig. 2.2.16).

However, 49 countries and areas reached a coverage of at least 80% in

2024.

Fig. 2.2.16 Percentage of people diagnosed with pre-XDR-TBa who were tested for resistance to linezolid, by country, 2024

HIV status

Of the 8.3 million people newly diagnosed with TB globally in 2024, 82% had a documented HIV test result, a slight increase from 81% in 2023 and 80% in 2022 (Fig. 2.2.17). At regional level, the highest percentages were achieved in the WHO African and European regions: 89% and 94%, respectively.

Fig. 2.2.17 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with TB whose HIV status was documented,a globally and for WHO regions,b 2010–2024

b Countries were excluded if the number of people with documented HIV status was not reported to WHO.

There was considerable variation at national level

(Fig. 2.2.18). In

101 countries and areas, at least 90% of people diagnosed with TB knew

their HIV status; this included 32 out of 47 countries (the same as in

2023) in the WHO African Region, where the burden of HIV-associated TB

is highest. In most countries, the percentage was above 50%. However, in

15 countries in 2024, less than half of the people diagnosed with TB

knew their HIV status: Argentina, Bangladesh, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland,

Japan, New Caledonia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Serbia,

Slovakia, the Solomon Islands, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen. This was down

from 20 countries in 2023.

Fig. 2.2.18 Percentage of people newly diagnosed with TB whose HIV status was documented, by country, 2024

Worldwide in 2024, a total of 413 516 new cases of TB among people living with HIV were notified (Table 2.1.1 of Section 2.1), equivalent to 6.2% of the 6.7 million people diagnosed with TB who had an HIV test result. Globally, the percentage of people diagnosed with TB who had an HIV-positive test result has been falling for many years, following a peak at 28% in 2006. WHO has compiled data on the number of people diagnosed with TB who had an HIV-positive test result since 2004.

Further country-specific details about diagnostic testing for TB, HIV-associated TB and anti-TB drug resistance are available in the Global tuberculosis report app and country profiles.

In 2023, WHO defined 12 benchmarks that can be used to assess and support progress towards universal access to rapid TB diagnostics (7). A WHO dashboard provides data and visualizations about country progress with respect to the standards.

Data shown on this webpage are as of 30 July 2025 (see Annex 2 of the core report document for more details).

References

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 3: Diagnosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/381003). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Consolidated guidance on tuberculosis data generation and use: module 1: tuberculosis surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376612). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Falzon D, Miller C, Law I, Floyd K, Arinaminpathy N, Zignol M et al. Managing tuberculosis before the onset of symptoms. Lancet Respir Med. 2025;13:14-5. (https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(24)00372-2).

Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the fight against tuberculosis. New York: United Nations; 2023 (https://www.un.org/pga/77/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2023/09/TB-Final-Text.pdf).

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment and care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/380799). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Meeting report of the WHO expert consultation on the definition of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, 27-29 October 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/338776). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

WHO standard: universal access to rapid tuberculosis diagnostics. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/366854). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

General disclaimers

The designations employed

and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning

the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or

boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border

lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.