2.3 TB treatment: coverage and outcomes

To minimize the ill health and mortality caused by tuberculosis (TB), everyone who develops TB disease needs to be able to promptly access diagnosis and treatment.

At the second United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on TB in 2023, Member States adopted a target that, by 2027, at least 90% of the estimated number of people who develop TB disease should be provided with quality-assured diagnosis and treatment (1).

There are still large gaps between the estimated number of people who develop TB each year (incident cases; see Section 1.1 for further details) and the number of people newly diagnosed with TB and officially reported as a TB case (Fig. 2.3.1). This reflects a mixture of (i) underdiagnosis and (ii) underreporting of people diagnosed with TB to national authorities.

Globally in 2024, the number of people who were newly diagnosed with TB and officially notified as a TB case (8.3 million) was 78% (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 72–84%) of the estimated number of incident cases. The gap, at 2.4 million, was lower than in 2023 (2.6 million) and has narrowed since 2020, a year in which it widened substantially (to a best estimate of 4.5 million) amid COVID-related disruptions in the first year of the pandemic.

Fig. 2.3.1 Number of people newly diagnosed with TB and officially notified as a TB case (new and recurrent cases,a all forms) (black) compared with the estimated number of people who developed TB (incident cases) (green), 2010–2024, globally and for WHO regions

Gaps between estimated incidence and the number of people newly diagnosed with TB and officially notified as a TB case have also been narrowing in most WHO regions (Fig. 2.3.1) and high TB burden countries (Fig. 2.3.2). The main exception is the Region of the Americas.

Fig. 2.3.2 Number of people newly diagnosed with TB and officially notified as a TB case (new and recurrent cases,a all forms) (black) compared with the estimated number of people who developed TB (incident cases) (green), 30 high TB burden countries,b 2010–2024

b Incidence estimates are not shown for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, since they are currently under review.

In comparing estimates of TB incidence with case notification data, it is important to highlight that notification data may be artificially inflated by overdiagnosis of TB, particularly among people diagnosed without bacteriological confirmation of disease. For example, the proportion of notified cases diagnosed based on bacteriological confirmation in 2024 was less than 50% in Papua New Guinea (45%) and the Philippines (46%) (Fig. 2.2.8 of Section 2.2). People correctly diagnosed with TB may also be missing from notification data, due to underreporting. In some countries, estimates of TB incidence would benefit from new studies (such as a national TB prevalence survey or national TB inventory study) to directly measure the underlying burden of TB disease in the population. For example, the main data sources used to inform the current estimates of TB incidence in Uganda and Zambia, countries in which notifications came very close to estimated levels of incidence in 2022 and 2022–2023 respectively, are national TB prevalence surveys that were implemented in 2014–2015 (Uganda) and 2013–2014 (Zambia) (Section 1.4).

In 2024, ten countries accounted for 63% of the global gap between the estimated number of people who developed TB (incident TB cases) and the number of people who were diagnosed with TB and officially reported as a TB case (Fig. 2.3.3). About 40% of the global gap was accounted for by five countries: Indonesia (10%), India (8.8%), the Philippines (7.5%), Pakistan (7.2%) and China (6.9%).

Fig. 2.3.3 The ten countries with the largest gaps between notifications of people newly diagnosed with TB and the best estimates of TB incidence, 2024a

Among people living with HIV who develop TB, both TB treatment and antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV are necessary to prevent unnecessary deaths from TB and HIV. Since 2019, the global coverage of ART for people newly diagnosed and reported with TB and known to be living with HIV has been maintained at a high level; in 2024 it reached 91%, up from 88% in 2023 (the blue curve compared with the black curve) (Fig. 2.3.4).

However, when compared with the total number of people living with HIV who are estimated to have developed TB in 2024 (the red curve), coverage was much lower, at 61%, almost unchanged from 60% in 2023. Among WHO regions, the highest levels of ART coverage among people living with HIV who developed TB in 2024 were achieved in the African Region (a best estimate of 67%); coverage was lowest in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (a best estimate of 33%).

Fig. 2.3.4 Estimated number of incident cases of TB among people living with HIV (red) compared with notifications of people newly diagnosed with TB who were known to be living with HIV (black) and the number of people living with HIV who were diagnosed with TB and started on antiretroviral therapy (blue), globally and for WHO regions, 2010–2024

All ART coverage estimates for people with TB are far below the overall coverage of ART for people living with HIV, which was 77% (95% UI: 62–90%) at the end of 2024 (3). The main reason for relatively low ART coverage for people with TB is the persistently large gap between the estimated number of people living with HIV who developed TB each year and the number of people living with HIV who are reported to have been diagnosed with TB.

At regional level, the biggest gaps in 2024 were in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions, where 57% and 47% respectively of the estimated number of people living with HIV who developed TB in 2024 were not diagnosed with TB and reported.

Among the 30 high TB/HIV burden countries, best estimates of the coverage of ART among people living with HIV who developed TB in 2024 varied widely, from 28% in Gabon to 91% in Kenya; only 19 of these 30 countries achieved coverage of at least 50% (Fig. 2.3.5).

Fig. 2.3.5 Estimated coverage of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV who developed TBa in 2024, 30 high TB/HIV burden countries, WHO regions and globally

b Data on the number of people living with HIV who were newly diagnosed with TB and on antiretroviral therapy were not reported by Liberia.

Globally, the treatment success rate for people treated for drug-susceptible TB with first-line regimens was 88% in 2023 (the latest year for which treatment outcome data are available), and ranged from 71% in the WHO Region of the Americas to 93% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (Fig. 2.3.6).

Fig. 2.3.6 Treatment outcomes for people diagnosed with TB in 2023 (new and recurrent casesa) who were treated for drug-susceptible TB using first-line regimens, WHO regions and globally

Globally, there were steady improvements in the treatment success rate between 2016 and 2023: from 81% in 2016 to 88% in 2023 (Fig. 2.3.7). The treatment success rate remains lower among people living with HIV, at 79% globally in 2023, but this is up from 75% in 2017 and far better than the level of 68% in 2012.

Fig. 2.3.7 Treatment outcomes for people diagnosed with TB (new and recurrent casesa) who were treated for drug-susceptible TB using first-line regimens, 2012–2023

Among WHO regions, the best treatment success rate among people living with HIV was achieved in the African Region, where the burden of HIV-associated TB is highest (Fig. 2.3.8).

Fig. 2.3.8 Treatment outcomes for people living with HIV who were diagnosed with TB (new and recurrent casesa) who were treated for drug-susceptible TB using first-line regimens, WHO regions and globally, 2023

Among the 49 countries in one of the three global lists of high burden countries (for TB, HIV-associated TB and MDR/RR-TB) being used by WHO in the period 2021–2025 (see Annex 3 of the core report document), 31 reported treatment outcome data disaggregated by sex. The treatment success rate in women and girls was 90% in 2023, slightly higher than that among men and boys (87%) (Fig. 2.3.9).

Fig. 2.3.9 Treatment outcomes for people diagnosed with TB (new and recurrent casesa) who were treated for drug-susceptible TB using first-line regimens, disaggregated by sex for 31 high burden countries that reported data,b 2019–2023

b WHO has requested data on treatment outcomes disaggregated by sex from the 49 countries in one of the three lists of high burden countries (for TB, HIV-associated TB and MDR/RR-TB) since the 2021 round of global TB data collection. The countries from which such data are requested may be expanded in future (for example, to include all countries with case-based digital surveillance systems for TB).

The treatment success rate for people aged 0–14 years was 92% in 2023 (Fig. 2.3.10). Among the six WHO regions, the best treatment success rate among people aged 0–14 years was achieved in the African Region (94%).

Fig. 2.3.10 Treatment success rates for people aged 0–14 years who were diagnosed with TB (new and recurrent casesa), WHO regions and globallyb, 2023

b Data were reported by 135 countries on outcomes for 546 655 people aged 0–14 years, equivalent to 79% of the 695 313 cases among people aged 0–14 years that were notified in 2023.

The provision of TB treatment, as well as the provision of ART to people living with HIV, has averted millions of deaths (Table 2.3.1).

Table 2.3.1 Cumulative number of deaths (in millions) averted by a) TB treatment as well as b) antiretroviral treatment for people diagnosed with TB who were also living with HIV, globally and by WHO region, 2010–2024

| WHO region | Best estimate | Uncertainty interval | Best estimate | Uncertainty interval | Best estimate | Uncertainty interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 6.6 | 5.4–7.7 | 5.2 | 4.4–6.0 | 12 | 10–13 |

| Region of the Americas | 1.5 | 1.4–1.6 | 0.27 | 0.24–0.29 | 1.8 | 1.6–1.9 |

| South-East Asia Region | 17 | 14–19 | 0.85 | 0.52–1.2 | 18 | 15–20 |

| European Region | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 | 0.25 | 0.22–0.28 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.7 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 4.2 | 3.6–4.7 | 0.056 | 0.024–0.088 | 4.2 | 3.7–4.8 |

| Western Pacific Region | 14 | 13–16 | 0.42 | 0.34–0.50 | 15 | 13–16 |

| Global | 45 | 40–50 | 7.0 | 6.0–7.9 | 52 | 46–57 |

The combination of TB treatment and ART for people living with

HIV is estimated to have averted 9.8 million deaths between 2005, the

first year following the release of an interim WHO policy on

collaborative TB/HIV activities in 2004 (4), and 2024.

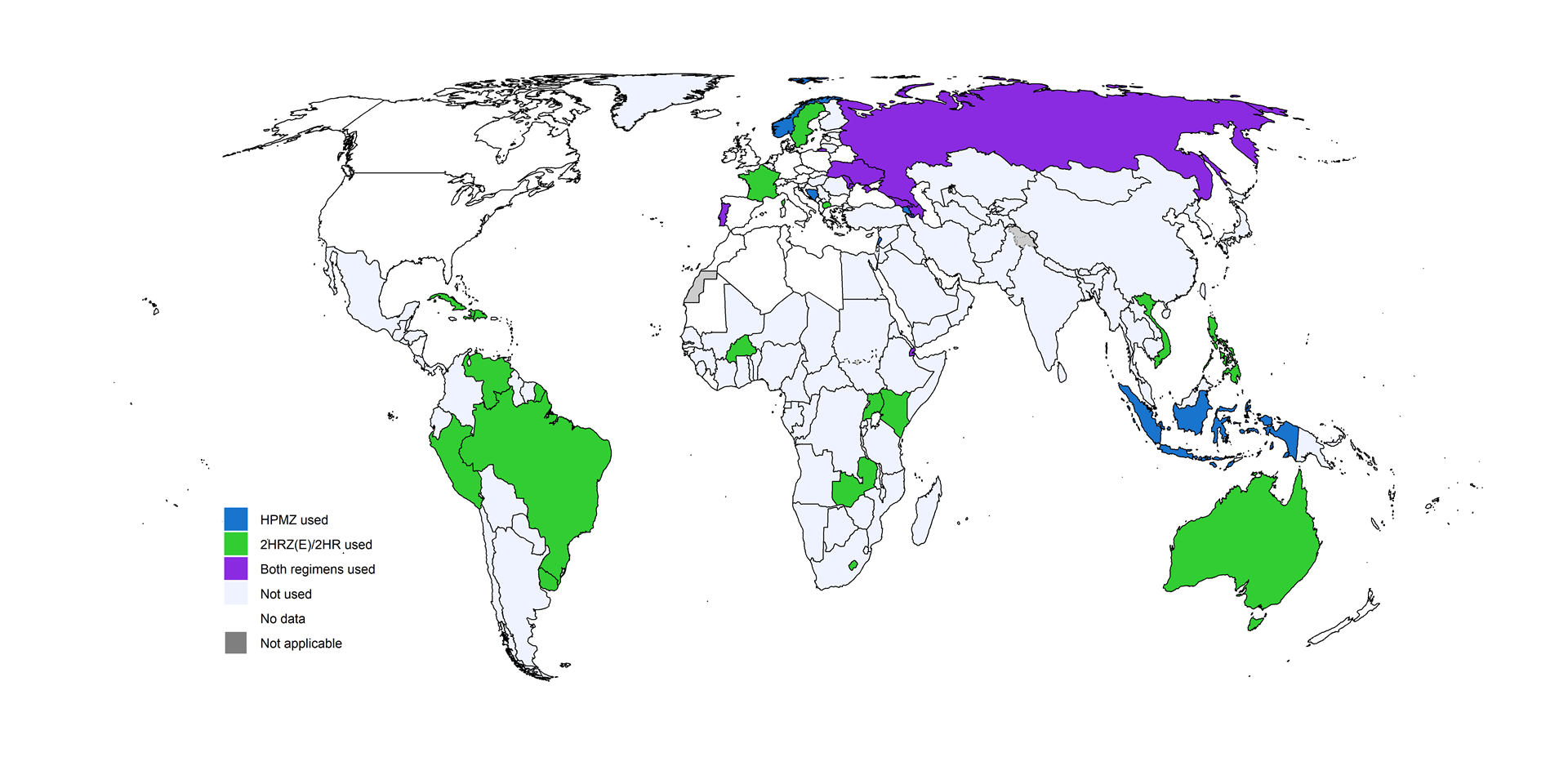

The most widely-used drug regimen for treatment of drug-susceptible TB lasts 6 months. Since 2022, a shorter 4-month regimen consisting of isoniazid, rifapentine, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide (HPMZ) has also been recommended by WHO for the treatment of rifampicin-susceptible TB (5). For people aged between 3 months and 16 years with non-severe TB, a 4-month regimen composed of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol (2HRZ(E)/2HR) has also been recommended since 2022 (5,6). To date, the 4-month regimens have not been widely used.

Globally in 2024, 4154 people diagnosed with TB were reported to have been started on treatment with the 4-month HPMZ regimen, up from 1271 in 2023. A total 15 countries and areas reported using the regimen by the end of 2024: Armenia, Aruba, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Djibouti, Dominica, Georgia, Indonesia, Lebanon, Norway, Portugal, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Sint Maarten (Dutch part) and Ukraine. This was an increase from five countries in 2023.

Globally in 2024, a total of 4487 people were started on treatment with the 2HRZ(E)/2HR regimen, up from 409 in 2023. A total of 26 countries and areas reported using the regimen by the end of 2024: Australia, Azerbaijan, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cuba, Djibouti, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, France, Georgia, Haiti, Kenya, Lesotho, North Macedonia, Peru, the Philippines, Portugal, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Sweden, Uganda, Ukraine, Uruguay, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Viet Nam and Zambia, up from 15 countries and areas in 2023 (Fig. 2.3.11).

Fig. 2.3.11 Countries that reported using 4-month regimens for treatment of rifampicin-susceptible TB by the end of 2024

Further country-specific details about the gap between TB incidence and notifications and treatment outcomes are available in the Global tuberculosis report app and country profiles.

Data shown on this webpage are as of 30 July 2025 (see Annex 2 of the core report document for more details).

References

Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the fight against tuberculosis. New York: United Nations; 2023 (https://www.un.org/pga/77/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2023/09/TB-Final-Text.pdf).

Consolidated guidance on tuberculosis data generation and use: module 1: tuberculosis surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376612). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Global HIV & AIDS statistics – fact sheet [website]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2025 (https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet).

Interim policy collaborative TB/HIV activities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/78705).

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis, Module 4: Treatment and care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/380799). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: Module 5: Management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/352522). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

General disclaimers

The designations employed

and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning

the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or

boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border

lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.