4. Financing for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services

Progress in reducing the burden of tuberculosis (TB) disease requires adequate funding sustained over many years. The World Health Organization (WHO) began annual monitoring of funding for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services, based on data reported by national TB programmes (NTPs) in annual rounds of global TB data collection, in 2002. Findings have been published in global TB reports and peer-reviewed publications (1–3). Recognizing that not all international donor funding for TB is captured in the data reported to WHO, each year WHO complements its analysis of data reported by NTPs with an assessment of international donor funding for TB using donor reports to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (see featured topics). Since 2005, funding for TB research has been monitored by the Treatment Action Group, with findings published in an annual report (4).

The Stop TB Partnership’s Global Plan to End TB, 2018–2022 (the Global Plan) estimated that US$ 8.6 billion was required for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services in 128 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in 2018, rising to US$ 15 billion in 2022 (5) (Fig. 4.1). It was estimated that an additional US$ 2 billion per year was needed for TB research. At the first United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on TB in 2018, Member States committed to mobilizing at least US$ 13 billion per year for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services by 2022, and an additional US$ 2 billion per year for TB research in the 5-year period 2018–2022.

a Funding estimates for collaborative TB/HIV activities exclude the cost of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for TB patients living with HIV. Such costs are included in global estimates of the funding required for HIV, published by UNAIDS.

The current Global Plan, for 2023–2030, estimates much higher funding needs, of US$ 15–32 billion per year in LMICs (6); this includes funding for implementation of a new TB vaccine after 2027. The political declaration adopted at the second UN high-level meeting on TB, held in September 2023, includes funding targets to mobilize US$ 22 billion per year by 2027 for TB diagnostic, treatment and prevention services, and US$ 35 billion per year by 2030; a target of US$ 5 billion per year by 2027 was set for investment in TB research (7).

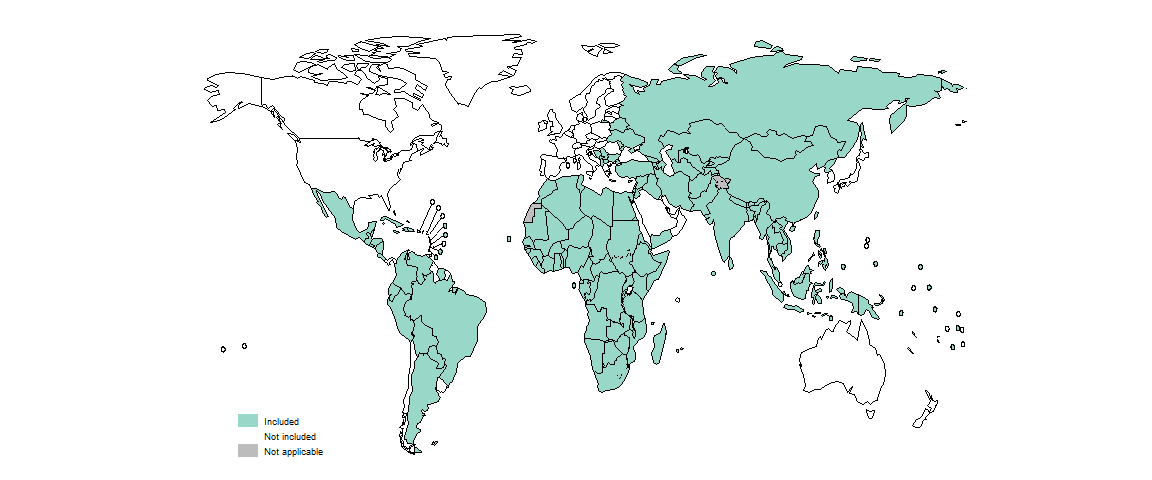

Data about funding available for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services by major category of expenditure and source of funding in the 10-year period 2013–2022 have been reported to WHO by 134 LMICs (Fig. 4.2). These countries accounted for 99% of reported TB cases globally in 2022.

Funding available for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services in LMICs falls far short of the globally estimated need and the UN global targets, and has fallen since 2019. In 2022, the total was only US$ 5.8 billion (Fig. 4.3). This is less than half of the amounts estimated to be required in 2022 in the Global Plan (2018–2022) and the global target set at the UN high-level meeting on TB in 2018.

Fig. 4.3 Funding available for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services in 134 low- and middle-income countriesa,b with 99% of reported TB cases in 2022, compared with the global target set at the 2018 UN high-level meeting on TB of at least US$ 13 billion per year, 2018–2022

a Values for 2018–2021 are higher than those shown in the Global Tuberculosis Report 2022, since they have been inflated (for comparability with data for 2022) to constant US$ values for 2022.

b In a small number of countries (nine countries in 2022, which accounted for 0.38% of the number of TB cases notified globally), TB funding data were not reported to WHO and funding amounts could not be estimated from available data. For these countries, only the estimated financial costs associated with inpatient and outpatient treatment were included.

Explanations for the decline in total available funding for TB between 2019 and 2020–2021 include reductions in the global number of people reported as diagnosed with TB in 2020 and 2021, compared with 2019 (Section 2); changes to models of service delivery (e.g. fewer visits to health facilities and more reliance on remote support during treatment); and reallocation of resources to the COVID-19 response. While 2022 saw an impressive rebound in the number of people newly diagnosed and notified with TB (Fig. 2.1.1 in Section 2.1), there was no comparable rebound in the total funding available for TB service delivery.

Longer-term trends in total funding by category of expenditure show an increase between 2013 and 2014, a decline up to 2016, limited growth up to 2019, a fall in 2020 and stabilization in 2021–2022 (Fig. 4.4).

a The category of drug-susceptible TB includes funding reported by NTPs for the following items: laboratory equipment and supplies; anti-TB drugs; programme management (including staff and activities); operational research and surveys; patient support; and miscellaneous items. It also includes WHO estimates of funding for inpatient and outpatient care for people treated for drug-susceptible TB, which are based on WHO estimates of the unit costs of bed-days and visits combined with the average number of outpatient visits and bed-days per TB patient as reported by NTPs.

b The category of drug-resistant TB includes funding reported by NTPs for the following items: anti-TB drugs required for treatment of multidrug and rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB, which includes people with pre-extensively drug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB, XDR-TB); any programme management (staff and activity) costs specifically required for the provision of care to people with drug-resistant TB; and WHO estimates of funding for inpatient and outpatient care. The categories for which funding is reported to WHO do not allow for funding for the diagnosis of drug-resistant TB specifically to be distinguished. In data analysis, the category of laboratory supplies and equipment is allocated to drug-susceptible TB. Rapid tests recommended by WHO can detect TB and RR-TB simultaneously.

c Data for TB preventive treatment (drugs only) are only available from 2019 onwards.

Since 2014, funding available for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-susceptible TB has fallen slightly. Funding available for treatment and management of drug-resistant TB has increased since 2015: this growth is largely explained by trends in the BRICS group of countries (Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa) (Fig. 4.5).

BRICS: Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China, South Africa.

a The two global TB watchlist countries included are Cambodia and Zimbabwe.

b The category of drug-susceptible TB includes funding reported by NTPs for the following items: laboratory equipment and supplies; anti-TB drugs; programme management (including staff and activities); operational research and surveys; patient support; and miscellaneous items. It also includes WHO estimates of funding for inpatient and outpatient care for people treated for drug-susceptible TB, which are based on WHO estimates of the unit costs of bed-days and visits combined with the average number of outpatient visits and bed-days per TB patient as reported by NTPs.

c The category of drug-resistant TB includes funding reported by NTPs for the following items: anti-TB drugs required for treatment of multidrug and rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB, which includes people with pre-extensively drug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB, XDR-TB); any programme management (staff and activity) costs specifically required for the provision of care to people with drug-resistant TB; and WHO estimates of funding for inpatient and outpatient care. The categories for which funding is reported to WHO do not allow for funding for the diagnosis of drug-resistant TB specifically to be distinguished. In data analysis, the category of laboratory supplies and equipment is allocated to drug-susceptible TB. Rapid tests recommended by WHO can detect TB and RR-TB simultaneously.

Funding available by source shows a relatively consistent pattern in terms of the amounts and relative contributions from domestic and international donor sources (Fig. 4.6). In 2022, 80% of the funding available for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services was from domestic sources, similar to previous years. From 2019 to 2022, there was a decline in available funding from domestic sources (US$ 0.78 billion) and a very slight increase in funding provided by international donors (US$ 0.07 billion).

The main source of international donor funding for TB is the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund). Its share of the total amount of international donor funding reported by NTPs to WHO was 75% in 2022. A comprehensive analysis of international donor funding for TB, including additional funding that is not channeled through NTPs, is one of the featured topics of this report. Key findings include that the United States Government (USG) is the largest contributor of funding to the Global Fund and also the largest bilateral donor for TB; it contributes about 50% of international donor funding for TB.

Aggregate figures for the shares of funding from domestic and international sources in LMICs are strongly influenced by the BRICS group of countries. In combination, BRICS accounted for US$ 3.0 billion (65%) of the total of US$ 4.7 billion in 2022 that was provided from domestic sources (Fig. 4.7). Overall, 94% of available funding in BRICS and all funding in Brazil, China and the Russian Federation in 2022 was from domestic sources. In other LMICs, international donor funding remains crucial. For example, in 2022 such funding accounted for 52% of the funding available in the 26 high TB burden and two global TB watchlist countries (Cambodia and Zimbabwe) outside BRICS, and 61% of the funding available in low-income countries (LICs).

BRICS: Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China, South Africa.

a The two global TB watchlist countries included are Cambodia and Zimbabwe.

b Asia includes the WHO regions of South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.

c “Other regions” consists of three WHO regions: the Eastern Mediterranean Region, the European Region, and the Region of the Americas.

Bangladesh, Mongolia, the Philippines and Sierra Leone are examples of high TB burden countries that have increased domestic funding specifically allocated to NTPs (as opposed to funding allocated more generally for inpatient and outpatient care, including for people with TB) in recent years (Fig. 4.8). There were also substantial increases up to 2019 in China. Domestic funding has also risen in one of the global TB watchlist countries: Cambodia.

a The three global TB watchlist countries are Cambodia, the Russian Federation and Zimbabwe (Annex 3).

In 2022, 62 of the 134 LMICs reported that funding was not sufficient for full implementation of their national strategic plans for TB. The total funding gaps reported amounted to US$ 1.5 billion (Fig. 4.9), with the largest gaps reported by Indonesia (US$ 264 million), Nigeria (US$ 261 million), the Philippines (US$ 207 million) and Viet Nam (US$ 106 million). Of the 26 LICs, 19 (73%) reported funding gaps that amounted to US$ 219 million in 2022.

The funding gaps reported by countries are much smaller than the gap between the estimated needs in the Global Plan and the amount of funding available in 2022. For example, in LICs the reported funding gap (US$ 0.22 billion) is approximately 16% of the gap (US$ 1.4 billion) between the estimated needs in the Global Plan (US$ 1.6 billion) and the amount of funding available to LICs in 2022 (US$ 0.25 billion) (5). The funding gap reported by LICs for 2023 is even lower (8.0%; US$ 0.15 billion compared with an estimated US$ 1.8 billion by the Global Plan) (6). A likely explanation is that the targets included in national strategic plans for TB in the LICs are much less ambitious than those set out in the Global Plan.

The total reported gap in 2022 amounted to US$ 1.5 billion and in 2023 amounted to US$ 1.6 billion.

Increases in both domestic and international funding for TB are urgently required. Variation in the share of funding from domestic sources within a given income group suggests that there is scope to increase domestic funding in some high TB burden and global TB watchlist countries (Fig. 4.10). Allocations by the Global Fund and its major donor (the US government, which is also the leading bilateral donor for TB) are currently the dominant influences on international donor funding for TB (see also the featured topics section of this report).

b Two countries i.e the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Sierra Leone had not reported budget data for 2023 to WHO at the time of report preparation.

The median cost per person treated for TB in 2022, from a provider perspective, was US$ 807 for drug-susceptible TB (Fig. 4.11).

b Limited to countries with at least 100 patients on first-line treatment in 2022, that reported funding and utilisation data to WHO.

The median cost per person treated for drug-resistant TB, from a provider perspective, was US$ 5047 in 2022 (Fig. 4.12). These amounts include all of the provider costs associated with treatment and TB programme-related costs.

a The following costs are included: anti-TB drugs; programme management (staff and activity) costs specifically required for the provision of care to people with drug-resistant TB; inpatient and outpatient care.

b Limited to countries with at least 20 patients on second-line treatment in 2022, that reported funding and utilisation data to WHO.

Estimates of the costs incurred by TB patients and their

households during diagnosis and treatment are available from national

surveys

(Section 5.2).

Further details about funding for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services are available in online country profiles and the Global Tuberculosis Report mobile app. Methods for data collection and analysis are described in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1

Methods used to compile, review, validate and analyse financial data reported to WHO

WHO began monitoring government and international donor financing for TB prevention, diagnostic and treatment services in 2002. All data are stored in the WHO global TB database. The standard methods used to compile, review, validate and analyse these data are described in detail in a technical appendix; this box provides a summary.

Systematic data review and validation have remained consistent since 2002. They include routine checks for plausibility and consistency, and discussions with country respondents to resolve queries. In reviewing and validating data, particular attention has always been given to high TB burden countries.

Missing data are handled as follows:

The analysis of available funding for TB uses reported information on received funding. When received funding is not available for a given year, expenditure data are used. If data on received funding and expenditure are both unavailable, data on committed funds are used. If none of these data are available, received funding, expenditure or committed funds from adjacent years are used. For analysis of funding in 2022, received funding was replaced by one of these methods in 35 countries, which collectively accounted for 9.7% of the global number of notified cases in 2022 ( this included two high burden countries, Nigeria and South Africa, which in combination accounted for 6.6% of the global number of notified cases). Nine countries (collectively accounting for 0.38% of the global number of notified cases in 2022) did not have sufficient data for any of the above methods to be applied; the estimated financial costs associated with inpatient and outpatient treatment were the only components included for these countries, using the methods described below.

When the breakdown of received funding by source or by category are missing for a given year, country-specific shares from the previous year are applied instead.

Since TB funding reported by NTPs does not usually include the financial costs associated with the inpatient and outpatient care required during TB treatment (exceptions among high TB or MDR/RR-TB burden countries include Belarus, China, Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation), country-specific estimates of the funding required for both inpatient and outpatient care are added. This is done by multiplying the reported number of TB patients notified by the product of the average number of bed days and outpatient visits per patient (as reported by NTPs) and their respective unit costs; this is done separately for TB patients with drug-susceptible TB and drug-resistant TB. Unit costs are estimated using the WHO CHOosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective (WHO-CHOICE) methods. Estimates of the costs of inpatient and outpatient care are produced for people with drug-susceptible TB and MDR/RR-TB separately.

Trend data are shown in constant (as opposed to current) 2022 US

dollars. In other words, funding amounts are shown in real terms, after

adjustment for inflation. Figures and tables that show data for 2022

only are labelled as current 2022 US dollars.

Note: Data sources for Figs 4.3–4.12: Data reported by NTPs and estimates produced by the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme. The data sources, boundaries, accounting rules, and estimation methods used in this report are different from those of the System of Health Accounts 2011 (SHA2011). The TB funding data reported here are thus not comparable with the disease expenditure data, including for TB, that are reported in WHO’s Global Health Expenditure Database.

References

Floyd K, Fitzpatrick C, Pantoja A, Raviglione M. Domestic and donor financing for tuberculosis care and control in low-income and middle-income countries: an analysis of trends, 2002–11, and requirements to meet 2015 targets. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(2):e105–15 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25104145).

Floyd K, Pantoja A, Dye C. Financing tuberculosis control: the role of a global financial monitoring system. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(5):334–40 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17639216).

Su Y, Garcia Baena I, Harle AC, Crosby SW, Micah AE, Siroka A et al. Tracking total spending on tuberculosis by source and function in 135 low-income and middle-income countries, 2000-17: a financial modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:929-42. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32334658/).

Treatment Action Group, Stop TB Partnership. Tuberculosis research funding trends 2005–2021. New York: Treatment Action Group; 2022 (https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/tb_funding_2022.pdf).

The Global Plan to End TB, 2018–2022. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership; 2019 (https://www.stoptb.org/previous-global-plans/global-plan-to-end-tb-2018-2022).

The Global Plan to End TB, 2023–2030. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership; 2022 (https://www.stoptb.org/global-plan-to-end-tb/global-plan-to-end-tb-2023-2030).

Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the fight against tuberculosis. New York: United Nations; 2023 (https://www.un.org/pga/77/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2023/09/TB-Final-Text.pdf).