Priority Area 3: Data supporting hepatitis responses

While nationally representative serosurveys are the reference methodology for determining the prevalence of HBV and HCV, many countries have relied on mathematical modelling using available data to establish disease burden estimates. Globally, WHO applies the HCV estimates from the Polaris Observatory established by the Center for Disease Analysis (CDA). Modelled estimates for HBV are available from several sources, including CDA, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Imperial College London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Some countries from the Region have engaged in modelling exercises with CDA (Cambodia, Fiji, Kiribati, Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Viet Nam) and Imperial College (China). This has helped establish government ownership of the estimates.

Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea have produced their own estimates of national HBV and HCV infection numbers. Hong Kong SAR (China) and Singapore are in the process of refining their disease burden estimates. Economic analyses and treatment cost-effectiveness analyses[1] have been completed in China, Cambodia, Fiji, Kiribati, Mongolia and Viet Nam for at least HBV or HCV (Table 2).

____________

[1] The Hep B Calculator and The HCV Calculator

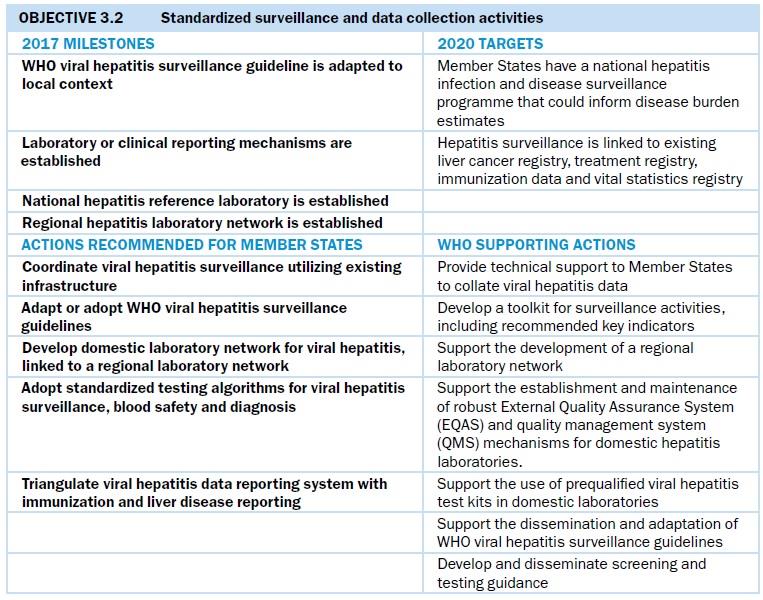

Standardized surveillance and data collection activities

Data collection and surveillance

Across the Region, national acute, chronic and sequelae surveillance systems are at various development stages (Fig. 10). Most countries have mandatory reporting of viral hepatitis cases detected as part of the notifiable disease system, but some do not distinguish between acute and chronic infections. Also, most of the national case-reporting systems in the Region include only syndromic reports of viral hepatitis, rather than reporting by type of hepatitis. Several countries are conducting enhanced acute surveillance, which includes the use of immunoglobulin M (IgM) markers with clinical data to ascertain new infection, along with epidemiological data collection to determine risk factors for new infections. In China, sentinel surveillance of acute hepatitis B infection takes place in 200 sentinel counties where acute viral hepatitis is diagnosed using a standardized algorithm based on IgM in vitro diagnosis. Mongolia has robust data collection for acute surveillance, including assigning epidemiologists to investigate acute HBV and HCV infections. It is also planning a case-control study to identify sources of new HCV infection. Viet Nam has enhanced acute and sequelae surveillance in three sentinel hospitals and is planning to expand to additional sites.

National seroprevalence surveys for chronic hepatitis, needed to estimate testing and treatment needs, are being conducted in Australia, China, Hong Kong SAR (China), Mongolia and New Zealand. A study is also under way in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Viet Nam. Demonstrating a cost-effective approach to implementing surveys, Hong Kong SAR (China) plans to integrate viral hepatitis into a government survey on noncommunicable diseases (NCD) in 2020. Australia and Mongolia have set up health information systems that capture the cascade of care, specifically the numbers of people diagnosed positive, with initiated HBV treatment or on HCV treatment, who are virally suppressed for HBV or cured for HCV. Mongolia’s information system for viral hepatitis is built into the national health insurance reimbursement systems and therefore obtains real-time data for over 800 000 records. In Australia, where people who inject drugs (PWID) are a key population affected by HCV, the HCV cascade for PWID has been estimated to monitor progress across testing, care and treatment services. Data have been used to demonstrate the feasibility of HCV elimination among PWID, reporting for the first-time population-level decline in viraemia following HCV DAA roll-out. In Brunei Darussalam, a national health information system includes an electronic patient monitoring system linking all public-sector health facilities, and has the potential to track patient outcomes over time. However, most countries do not yet have a national reporting system to obtain these data systematically.

Surveillance of long-term sequelae is very difficult, as many countries lack the registration systems required to monitor diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Countries such as China with strong national cancer registries regularly publish studies on the proportion of cirrhosis and liver cancer patients who have HBV or HCV infection. China additionally conducts regular mortality surveys to determine the proportions of deaths from cirrhosis and liver cancer.