3. TB prevention and screening

Preventing tuberculosis (TB) infection and stopping progression from infection to disease are critical for reducing TB incidence to the levels envisaged by the End TB Strategy. The main health care interventions to achieve this reduction are TB preventive treatment (TPT), which the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends for people living with HIV, household contacts of people with TB and other risk groups (1, 2). Strategies to provide TPT are often linked to screening to find and treat people with TB earlier in the course of their disease and thus help to reduce transmission and improve outcomes (2). Other TB preventive approaches are TB infection prevention and control (TB IPC) (3) and vaccination of children with the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Addressing broader determinants that influence TB epidemics can also help to prevent TB infection and disease; these are discussed in Section 5.3.

3.1 TB preventive treatment

The global number of people living with HIV and household contacts of people diagnosed with TB who were provided with TPT increased from 1.0 million in 2015 to 3.6 million in 2019. There was then a sizeable reduction to 2.9 million in 2020 and 2021, probably reflecting disruptions to health services caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Fig. 3.1). There was a substantial recovery to 3.8 million in 2022, above the pre-pandemic level.

Between 2021 and 2022, there was a particularly noticeable increase in the number of household contacts enrolled on TPT: from 0.76 million to 1.9 million. In contrast, the number of people living with HIV who were enrolled on TPT fell, from 2.2 million in 2021 to 1.9 million in 2022.

The global target of providing TPT to 30 million people in the 5-year period 2018–2022, set at the United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on TB in 2018, was missed by a substantial margin (Fig. 3.2), mainly because insufficient numbers of household contacts were started on treatment. In contrast, the target for people living with HIV was far surpassed, although further scale-up will be needed to reach the target of providing TPT to 90% of people living with HIV by 2025 (4). This target was reaffirmed at the 2021 UN high-level meeting on HIV and AIDS (5).

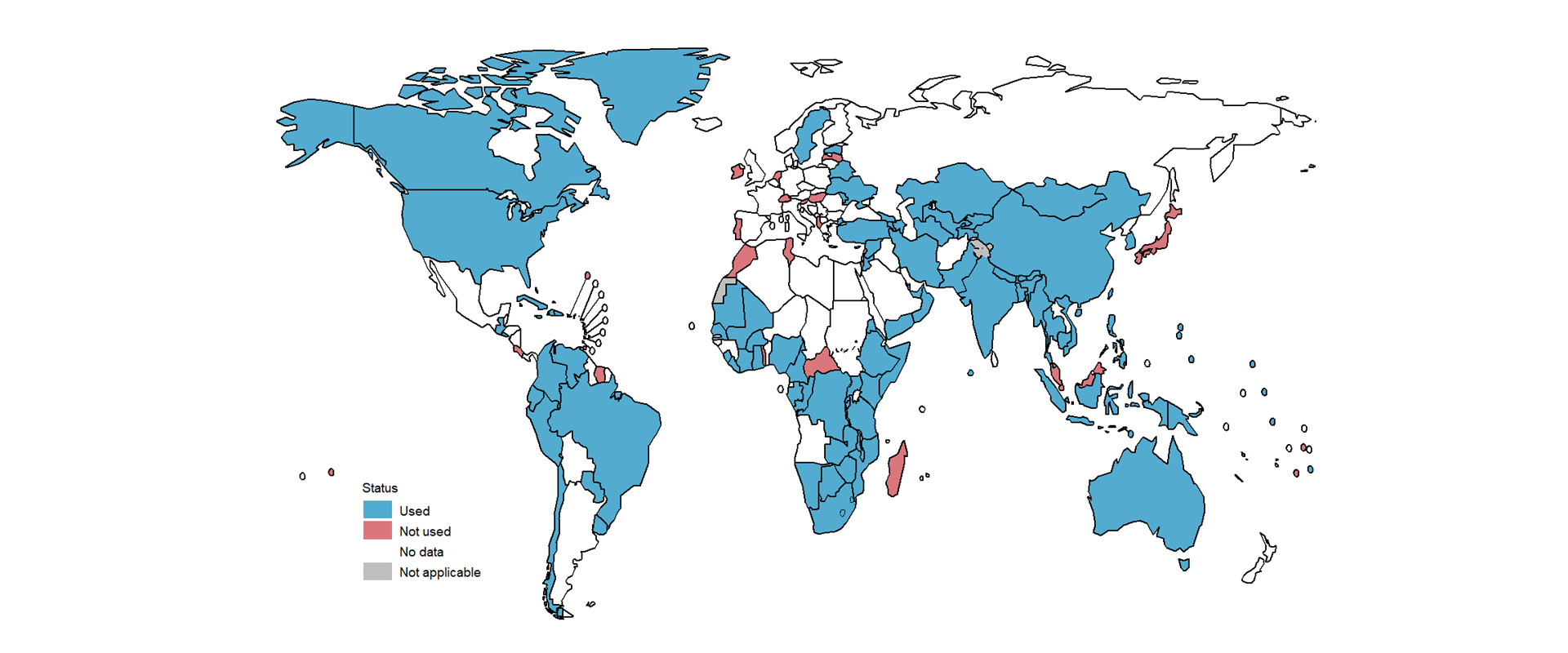

Ensuring access to shorter rifamycin-containing regimens may help to increase access to TPT. In 2022, 0.60 million people started shorter regimens in 74 countries. By December 2022, 96 countries reported having used shorter rifapentine-containing regimens (Fig. 3.3). In 2022 alone, 56 countries reported using the 3-month weekly regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid, and five reported using the 1-month daily regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid; also, 71 countries reported using a rifampicin-based regimen, of which 58 were using the 3-month daily regimen of rifampicin and isoniazid, and 36 were using the 4-month daily regimen of rifampicin only.

3.2 Household contacts

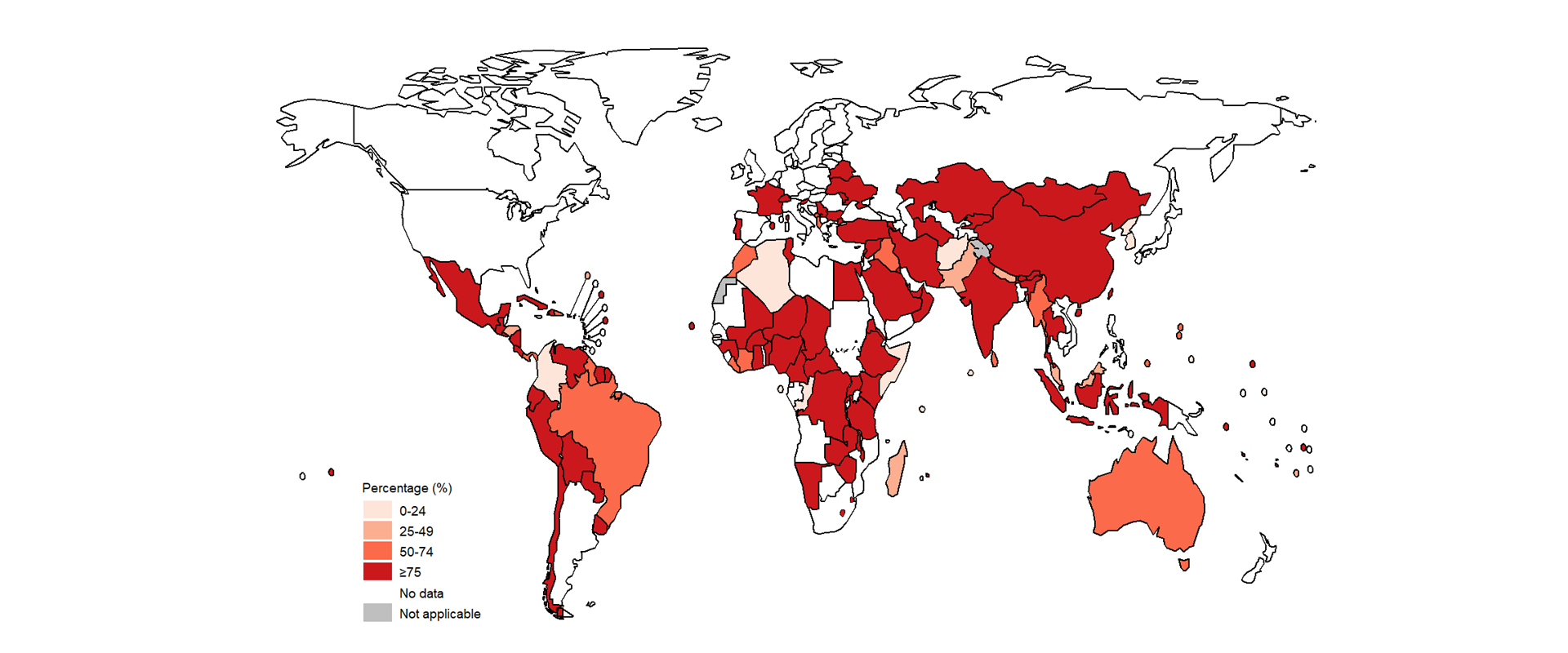

Globally in 2022, there were an estimated 13 million (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 12–13 million) household contacts of bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB cases of all ages. However, only 8.9 million contacts were reported in 2022 (up 14% from 7.9 million in 2021), with 7.1 million (80%) of these contacts evaluated for both TB infection and disease (up 12% from 6.4 million in 2021). The percentage of contacts who were evaluated varied widely among countries (Fig. 3.4).

A total of 1.3 million household contacts aged 5 years and over started TPT in 2022, representing a large (fourfold) increase compared with 2021 (Fig. 3.1). This change was driven by substantial increases in five high TB burden countries: Bangladesh, India, Nigeria, Uganda and Zambia.

In 2022, 0.59 million household contacts aged under 5 years started TPT (out of an estimated 1.6 million who were eligible) – a 40% increase compared with 2021.

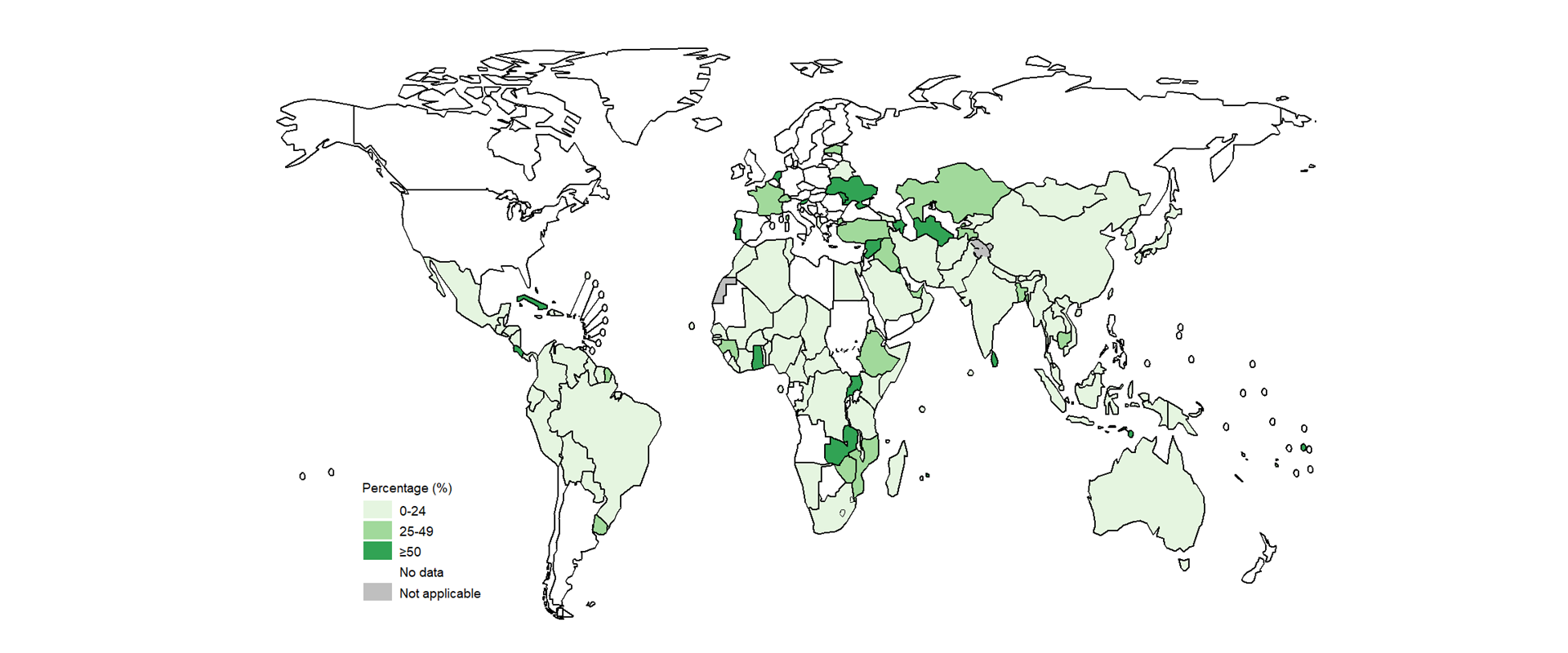

Globally, the 1.9 million household contacts provided with TPT in 2022 represented about 21% of the 8.9 million contacts reported and 15% of the 13 million contacts estimated. There was considerable variation among countries in both the percentage of household contacts who were evaluated for TB disease and infection, and the percentage of household contacts who were provided with TPT (Fig. 3.4, Fig. 3.5).

Data on completion of TPT among household contacts who started treatment in 2021 was reported by 83 countries; the median completion rate was 89% (interquartile range [IQR], 75–100%) but rates varied widely (Fig. 3.6).

Globally, the cascade of TB preventive care shows a big gap between the number of household contacts screened for TB disease and the number starting TPT (Fig. 3.7).

3.3 People living with HIV

Globally, the annual number of people living with HIV who received TPT increased from fewer than 30 000 in 2005 to 3.0 million in 2019 (Fig. 3.8). Since then, reported numbers have decreased, to 2.4 million in 2020, 2.2 million in 2021 and 1.9 million in 2022. There were declines in five of the six WHO regions between 2019 and 2021. In absolute terms, these declines were biggest in the WHO African Region. In 2022, there was a slight recovery in the WHO regions of the Americas, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. Possible reasons for the reductions include disruptions to health services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in data collection. The number of countries reporting data fell from 75 in 2019 to 66 in 2022.

Six countries provided TPT to more than 100 000 people living with HIV in 2022, and collectively accounted for 1.4 million (72%) of the global total in 2022: India, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Between 2005 and the end of 2022, 17 million people living with HIV were initiated on TPT, equivalent to just under half of the 39 million people estimated to be living with HIV in 2022 (6).

Among 61 countries that reported data, a median of 34% (IQR: 8.8–63%) of people living with HIV who were newly started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) received TPT in 2022.

In 31 countries that reported data, a median of 81% (IQR: 66–95%) of people living with HIV who started TPT in 2021 completed the treatment (Fig. 3.9).

3.4 Screening for TB disease in household contacts and other high-risk groups

Among 118 countries reporting the results of TB screening in household contacts in 2022, the overall yield was 2.8% (median: 2.0%; IQR: 0.43–5.4%) (Fig. 3.10). Four countries reported yields of between 3.3% and 4.0%, which is what would be expected in household contacts of people with bacteriologically confirmed TB (7): Algeria, the Central African Republic, Haiti and Mongolia. The wide variations in other countries probably reflects differences in the coverage of screening for eligible individuals, the diagnostic algorithms being used and the completeness of reporting.

In 2021 or 2022 (or both), 30 countries reported results from active TB case finding among risk groups other than household contacts; these groups included people living with HIV, incarcerated people, miners, migrants, people with diabetes, health care workers and people living in informal urban settings. The ratio of people screened to estimated TB incidence differed markedly among reporting countries, probably reflecting variation in policy, coverage and completeness of reporting (Fig. 3.11). In four countries (Cameroon, China, India and Thailand), the number of people screened exceeded 1 million in one year. Chest radiography was included in screening algorithms for at least one of the subpopulations being screened in most countries (with eight exceptions). In 42 subpopulations for which chest radiography was used, the diagnostic yield varied from 0% to 11% (median: 0.8%).

3.5 Tests for TB infection

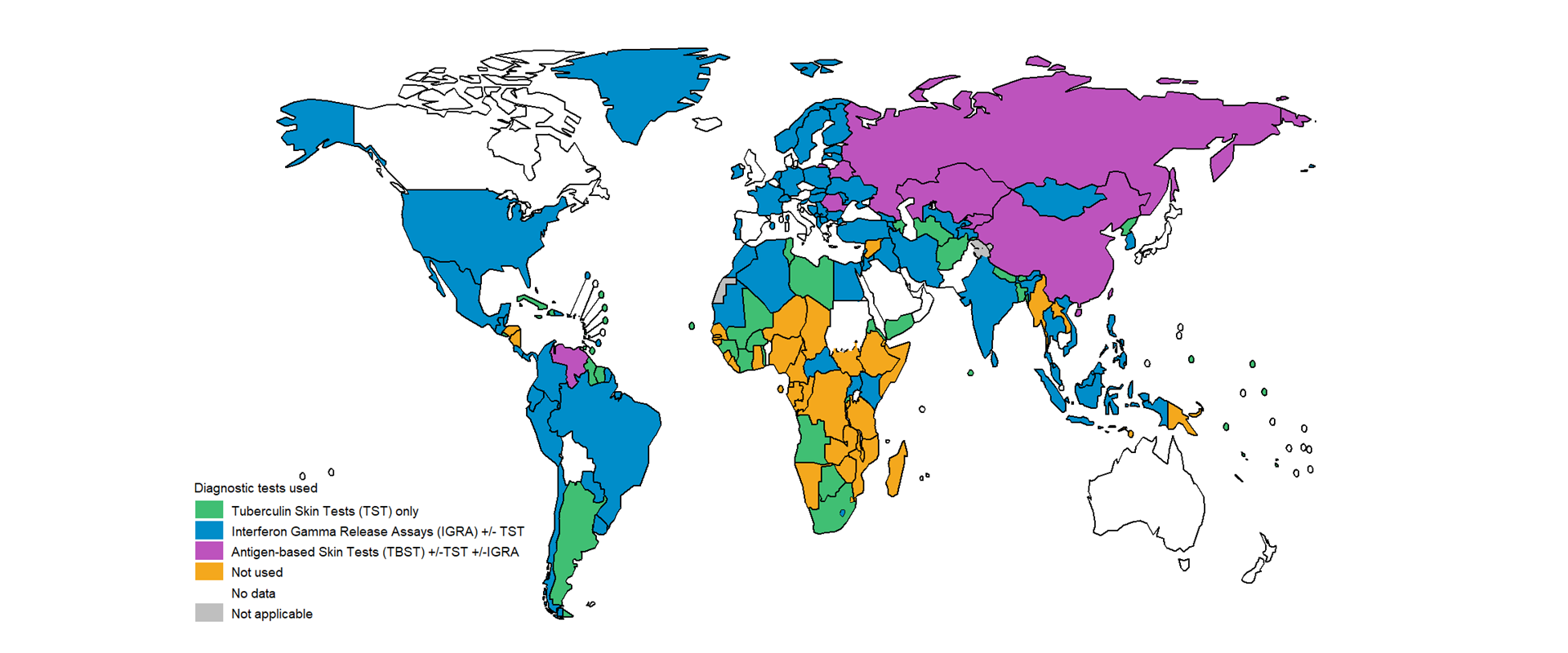

Tests for TB infection can help to target TPT to people who can gain the most benefit from it. In 2022, 116 countries reported using tuberculin skin tests (TST) or interferon gamma release assays (IGRA) in either the public or private sectors to deliver TPT to populations at risk (Fig. 3.12). A further eight countries reported using antigen-based skin tests in addition to IGRA or TST. Of the 36 countries reporting no use of tests for TB infection, 26 were in the WHO African Region.

3.6 TB infection prevention and control

Starting effective treatment as soon as possible after a diagnosis of TB is a key administrative measure to strengthen TB IPC. Six countries reported data on the interval between TB diagnosis and start of treatment in 18 patient cohorts between 2020 and 2022 (Table 3.1). In patients without multidrug-resistant or rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) or with an unknown drug resistance pattern, the mean interval ranged from 2 to 8.6 days (median 0–3 days). The delay was longer in people with MDR/RR-TB, with a mean of 14–112 days (median 12–97 days).

| Country | Source | Year | Number with MDR/RR-TB | Number with no known rifampicin resistance | Number with unknown resistance pattern | Mean days between TB diagnosis and start of treatment | Median days between TB diagnosis and start of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Special research | 2021 | — | 987 | — | 8.6 | 3.0 |

| Argentina | Special research | 2022 | — | 1 130 | — | 8.2 | 3.0 |

| Burkina Faso | Special research | 2018, 2020 | — | 331 | — | — | 2.0 |

| India | Health information system | 2022 | — | — | — | 3.7 | 1.0 |

| Ireland | Health information system | 2022 | — | 116 | — | 5.0 | 1.0 |

| Ireland | Health information system | 2022 | 10 | — | — | 14 | 12 |

| Ireland | Health information system | 2022 | — | 72 | — | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| Ireland | Health information system | 2022 | — | — | 28 | 2.0 | 0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2022 | 261 | — | — | 102 | 92 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2022 | — | 3 640 | — | 7.0 | 2.0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2022 | — | — | 20 300 | 4.0 | 0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2021 | 215 | — | — | 112 | 97 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2021 | — | 3 200 | — | 4.0 | 1.0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2021 | — | — | 17 100 | 4.0 | 0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2020 | 161 | — | — | 108 | 32 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2020 | — | 2 090 | — | 7.0 | 1.0 |

| Mexico | Health information system | 2020 | — | — | 14 500 | 4.0 | 0 |

| Romania | Health information system | 2020 | 262 | 483 | 2 600 | — | — |

| Romania | Health information system | 2021 | 263 | 5 540 | 2 160 | — | — |

| Romania | Health information system | 2022 | 270 | 6 390 | 2 610 | — | — |

| Slovenia | Health information system | 2021-2022 | 2.0 | 140 | 12 | 5.1 | 1.0 |

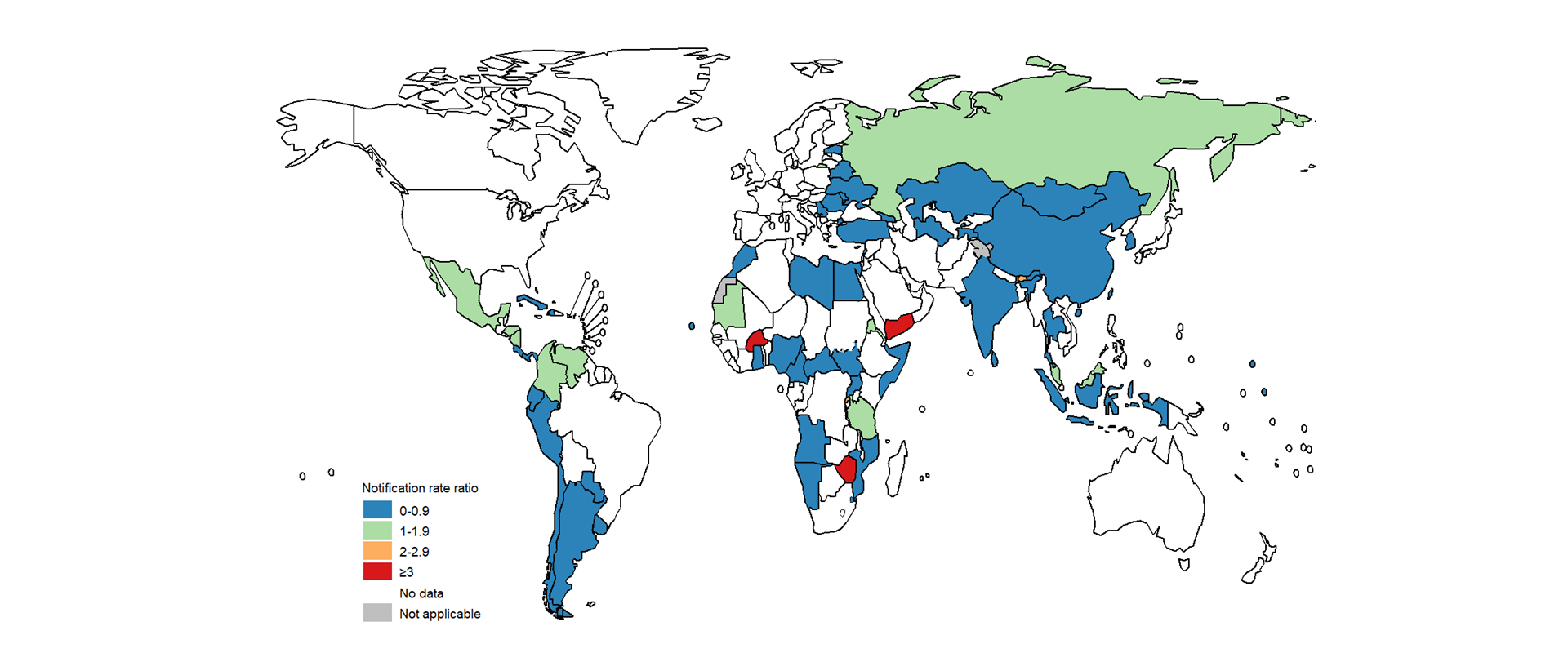

The risk of TB among health care workers relative to the risk in the general adult population is one of the indicators that WHO recommends for measuring the impact of interventions for TB IPC in health care facilities. If effective prevention measures are in place, the risk ratio for TB in health care workers compared with the general adult population should be close to 1. In 2022, 16 171 health care workers from 68 countries were reported to have been diagnosed with TB. The ratio of the TB notification rate among health care workers to the general adult population was greater than 1 in 14 countries that reported five or more TB cases among health care workers (Fig. 3.13).

3.7 Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination is recommended as part of national childhood immunization programmes, in line with a country’s TB epidemiology (8). However, global coverage dropped from 89% in 2019 to 84% in 2021, probably due to disruptions to health services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a recovery back to 87% in 2022 (Fig. 3.14) (9).

References

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 1: Prevention – Tuberculosis preventive treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/331170).

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 2: Screening – Systematic screening for tuberculosis disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/340255).

WHO guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control. 2019 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/311259).

Implementing the End TB Strategy: the essentials, 2022 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/365364).

United Nations General Assembly. 75th session. Item 10 of the agenda. Implementation of the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS and the political declarations on HIV/AIDS. Draft resolution submitted by the President of the General Assembly. Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Ending Inequalities and Getting on Track to End AIDS by 2030 (A/75/L.95). New York: United Nations; 2018 (https://www.un.org/pga/75/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2021/06/2107241E1.pdf).

UNAIDS epidemiological estimates, 2023 (https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/).

Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, Marks GB. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Respiratory Journal. 2013 Jan 1;41(1):140–56. (https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/41/1/140).

Weekly Epidemiological Record, 2018, vol. 93, 08, 73 - 96. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260306).

The WHO Global Health Observatory (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/bcg-immunization-coverage-among-1-year-olds-(-)). Data download 19 July 2023.